How did a Saint from Western Turkey become an elf-Lord driving reindeer around the North Pole? The journey of St. Nicholas through time, space and cultures has transformed this pious bishop of Myra into Santa: a secular, round-bellied, cheerful caricature of modern consumerism. How, exactly, did he get from there to here? And does anything of the original Nick remain in our Mr. Claus?

I will divide Saint Nicholas into several different phases: his historical life, his role as a medieval saint, and his modern reinvention. Although the stages of Nicholas’s development tend to fade into one another, I hope these sections will give a good idea of the progression of types and how each of these types were influenced by the history of the times.

Phase 1: The historical Nicholas

Very little is known for certain about the life of our Nicholas, beyond that he was bishop of Myra in the late third to early fourth century CE. It is possible that he was one of the few hundred bishops that attended the 325 CE Council of Nicaea, as the majority of those bishops were from the Eastern provinces and many were never named. However, none of Nicholas’s contemporaries mentions him specifically. It is an unfortunate accident of history that Saint Nicholas left no personal writings.

Despite this scarcity of evidence, it seems likely that Nicholas had at least existed. The earliest written reference to St. Nicholas of Myra surfaces about 250 years after the saint’s probable death, in an account of another man named Nicholas. St. Nicholas of Sion had apparently adopted Nicholas’s name as a tribute to the earlier saint. His account notes that there was a martyrium – a small structure built over the site of a saint’s grave or dedicated to their memory – which honoured St. Nicholas of Myra as early as the sixth century. The name and the martyrium in this account both indicate that the cult of St. Nicholas had flourished not long after his death. This is evidence at least that there was a man named Nicholas of Myra who was remembered as an extraordinarily good witness of the faith.

All the rest of the details of his life can only be gathered from legends. Michael the Archimandrite (814-42) claims that St. Nicholas, bishop of Myra, was born in the neighbouring town of Patara. [1] According to the same account he was an only child, the sole heir of large amounts of property. When his parents died, he decided to dedicate his vast wealth over the course of his life to charity and helping the impoverished. At Myra, he became a bishop at an early age and continued to act charitably and honourably. The Stratelatis, a hagiography which circulated in the sixth century, suggests that the bishop Nicholas loved justice and civil peace and was on good terms with the Emperor Constantine. [2] The account claims that St. Nicholas settled an angry mob at Andriake, the port of Myra, and helped imperial soldiers find lawbreakers. It also alleges that Nicholas saved three innocent people from being wrongfully executed on at least one occasion. It is very difficult to know how much of his legendary life story might have been historically accurate. While not all that is said about St. Nicholas in these accounts may be true, not all would necessarily be false either.

Phase 2: Medieval Saint

From at the sixth century onward, St. Nicholas of Myra had become an extremely popular and versatile saint. While he had originated in the East, he was widely venerated in the West as well, especially after Italian merchants stole and relocated his relics to Bari, Italy in 1087. Over the course of the intervening centuries a huge number of anecdotes were attributed to his life. Large compilations of legends like Symeon the Metaphrast’s tenth century hagiography of St. Nicholas demonstrate just how rich the corpus of St. Nicholas legends was at this time. Name a profession, and St. Nicholas was probably patron of it in some way or another.

For instance, one of the legends went that as a suckling infant, St. Nicholas abstained from his mother’s milk and fasted at exactly the right time on Wednesdays and Fridays that he would if he were a priest. This event was supposed to foreshadow his fated role as a young bishop of Myra. It also made him a patron of suckling infants.

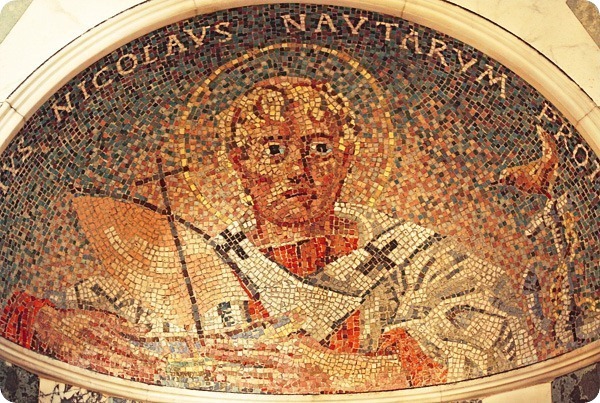

There was also a very popular legend that St. Nicholas had appeared to pilgrims who were sailing to see his tomb. When the ships were caught in a dangerous storm, the pilgrims prayed to Nicholas for help, and he miraculously made the storm subside. This anecdote explains why St. Nicholas is hailed as an important patron of sailors.

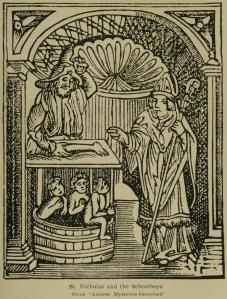

However it was his connection with children that would eventually link him to our Santa figure. One of the most famous of these was the horrifying Tale of the Butcher and the Three Children. Legend has it that there was a famine in the land and three kids wandered too far to get back home before sunset. Just as they were about to despair they spotted the house of a butcher and begged him to let them stay just for the night. The butcher agreed. But as soon as the door closed, he murdered the little children, butchered them, cut their meat into pieces and hid the pieces amongst similar-sized chunks of pork which was he pickling in a tub of brine.

Some time later – months or years, it varies among versions – St. Nicholas appeared at the butcher’s door. The butcher invited the bishop inside and tried to offer him something to eat, but St. Nicholas refused to take any meat from the butcher and asked instead, “What about the children in the tub of brine?” The butcher, overwhelmed by the guilt he had hidden for so long, confessed what he had done and repented. He showed St. Nicholas the tub with the dismembered children, and Nick simply commanded the children to rise up out of the brine. Miraculously the three children were revived and together they stumbled, disorientated, out of the tub.

The Tale of the Butcher remains a popular part of the St. Nicholas legend in France, where it is the subject of many colourful picture books and is delivered to children in song. In Anglophone culture, however, this story is largely unknown.

The other legend which links the medieval saint to modern Christmas traditions is the Tale of the Three Daughters (illustrated in the Eastern Orthodox fresco above). According to Symeon the Metaphrast’s hagiography, a man was stricken with poverty and could not afford to pay the dowries to marry off his three daughters. In order to survive, he contemplated selling his three daughters in turn to prostitution. When St. Nicholas heard of the family’s plight, he decided he would give the man bags filled with gold so he could afford his daughter’s dowries and not sell them into sexual slavery. But Nicholas wanted to remain anonymous, since he believed it was more virtuous to give without expecting fame or kudos from everyone else. So St. Nicholas tossed the bags through the man’s window in the middle of the night and ran away. Have you ever wondered why Santa Claus must arrive in the middle of the night and slip away without being seen? At least in this version of the story, the gift giver tries to keep out of sight because he wants his charity to remain anonymous.

In later medieval depictions of this story, a variant exists where the little bags of gold land in shoes or stockings. Note that in the fifteenth century Italian fresco above, the daughters are shown helping their father take off his stockings as everyone undresses before going to bed. This version of the tale was apparently acted out in medieval times when children were asked to hang up stockings on the Eve of St. Nicholas’s Feast (December 6th) and expect small gifts, like nuts and figs, stuffed into them in the morning. Note also that this fresco has simplified the shape of the three full bags of gold into three golden orbs. The three golden bags or golden orbs became part of St. Nicholas’s iconography, and later entered into the iconography of Christmas as those round golden baubles on trees.

In all, the medieval Saint Nicholas had an extremely rich and varied series of legends, and not all of them were about children. He was a popularly venerated saint, patron of almost everything from ships to butchers. The parts of him which became associated with Christmas celebrations are a tiny fraction of St. Nicholas’s legendary cycle. Nevertheless it seems that some of our Christmas practices, including the hanging of stockings, appear to date at least to the fifteenth century in Italy.

Phase 3: Modern Santas

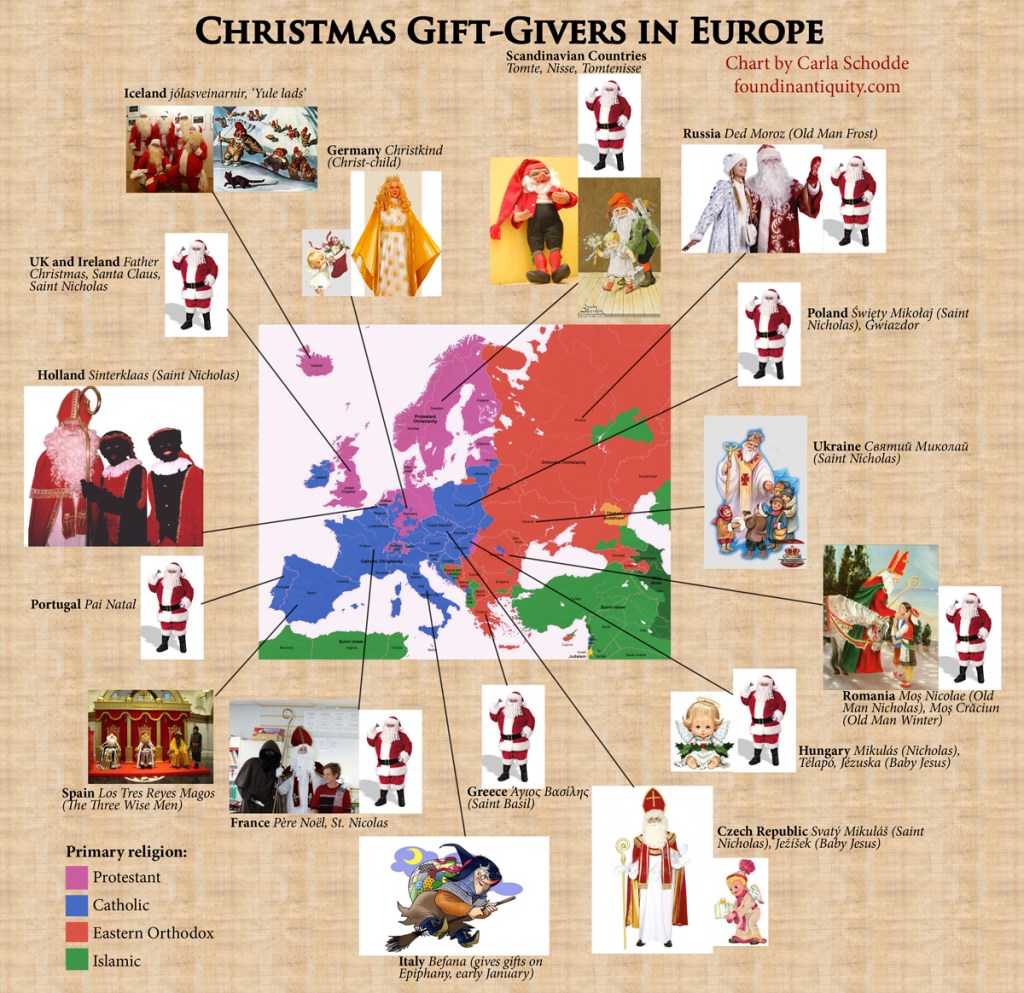

The medieval Saint Nicholas was unashamedly Catholic in appearance, often holding his bishop’s staff and wearing his bishop’s mitre. But after the Reformation, being too Catholic in a Protestant country was dangerous, and the veneration of saints attracted stern disapproval from religious authorities. This led various Protestant countries to replace St. Nicholas with other figures. In Germany, Martin Luther proposed that the gift-giving once associated with St. Nicholas’ Feast on December 6 should be moved to Christmas Day, and that the Christkind (or Christ Child) should substitute the saint as gift-bringer. Today, the Christkind in Germany has now changed from an angelic baby boy into an adult female angel, but in several Central European countries a small, winged, Baby Jesus figure still brings children their gifts.

Immediately after the Reformation in Britain, writers sometimes personified Christmas itself as a “Father Christmas,” as for instance Thomas Nashe did in his Summer’s Last Will and Testament, 1592.[3] “Father Christmas” initially appeared as a rhetorical figure, just as one would also personify a church or a country for literary effect. However, the name Father Christmas would later be conflated with the gift-bringer figure. During the Victorian revival of Christmas, St. Nicholas the gift-bringer also gained the name “Santa Claus” as a corruption of the Dutch “Sinterklaas,” or Saint Nicholas.

The 19th century English and American Santa Clauses are most closely related visually to the Scandinavian Tomte, which shares its name and appearance with an elf-like or gnome-like creature. Ever wondered why garden gnomes can look a lot like miniature Santas? It’s no coincidence, as both were based on similar brownie-like folk creatures.

Indeed, the early 19th century depictions of Santa Claus were a lot more gnome-like than the Santa of today. Thomas Moore’s poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” (1823) had St. Nicholas as a little old man, riding a miniature sleigh with tiny reindeer:

When, what to my wondering eyes should appear,

But a miniature sleigh, and eight tiny reindeer,

With a little old driver, so lively and quick,

I knew in a moment it must be St. Nick.

Not only is St. Nick a miniature figure, he is also rather tattered looking, “like a peddler just opening his pack.” The poem also explicitly describes St. Nick as a “right jolly old elf.” This poem stands as one of the earliest sources for the modern Anglophone vision of Santa. He is a tiny figure who travels around in a flying reindeer sleigh, and slips down peoples’ chimneys. And it may just be me, but it seems going down cramped Victorian chimneys made a lot more sense when Santa was more gnome-like in size and mannerisms, not like the fat, dad-sized figure he is now.

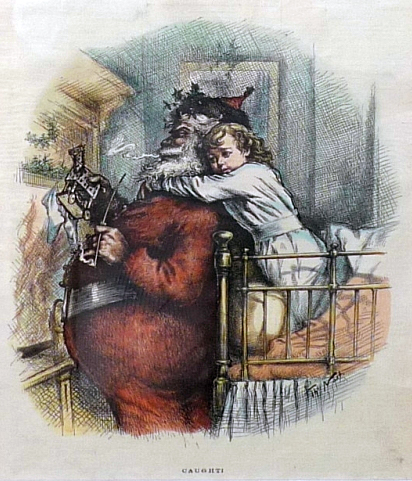

The American artist most often credited for popularising the modern image of Santa is Thomas Nast. But like Moore’s poem, Nast’s earlier drawings exhibit a much smaller Santa than the one we are now familiar with. Gradually, Nast’s engravings began to show Santa in larger scales relative to the children.

In the 1860s illustration above, Santa is an impish figure and is shown doing household activities, like a brownie. Note that he is smaller than a book and actually makes the Christmas toys himself. He has since become less elf-like in height, and has now outsourced his labor to smaller elves than himself. I feel like there’s some comment to make about industrial exploitation here, but I’ll leave it to you.

Nast’s 1870s drawing, “Seeing Santa Claus,” exhibits a larger Santa than the one above, but he is still only about the same size as the child he is delivering presents to.

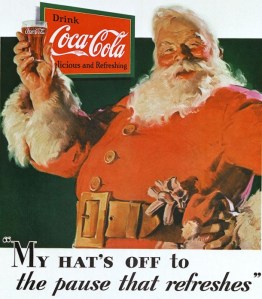

By the 1880s, Santa appears to have grown larger than any ordinary child, and indeed quite a bit taller than the fireplace from which he had supposedly emerged just a few moments ago. At last he seems to resemble everything that our familiar Santa Claus resembles. This image would continue to solidify right into the early 20th century, when it would eventually be featured on Coca-Cola advertisements. Coca-Cola did not coin the image of Santa Claus, but it could be seen as one of the later popularisers of this icon of consumerism.

But why the change in scale? Why wouldn’t St. Nick remain as diminutive as he was in Moore’s poem of 1823? I can only offer speculation. It is easier for children to sit in the lap of an adult-sized Santa. The tradition of dressing up as Santa Claus to ask children what they would want for Christmas appears to have been imported from 19th century Dutch customs,[4] and the Dutch Sinterklaas was conveniently human-sized. The gnome-based Santa of the 19th century probably took some traits and attributes from other Santa types which were in circulation at the time.

Our modern Santa Claus is indebted to several layers of history, both ancient and modern. It is probably no coincidence that the greatest amount of development of the modern Santa figure appears to have happened in and around the 19th century, a time of commercial prosperity, Nationalism, renewed interest in local folk customs and the birth of the fantasy genre. The study of St. Nicholas’ reception history has been very challenging to source, but I hope you enjoyed watching the transformation of this cultural icon.

[2] Stratelatis or The Military Officers, Anonymous Greek account from around AD 400, translated from Latin by Charles W. Jones. Source.

[4] Peter Eversmann, “The Feast of St. Nicholas in the Low Countries,” in Festivalising!: Theatrical Events, Politics and Culture, ed. Temple Hauptfleish et al. (Rodopi, 2007), 294-5.

5 responses to “Saint Nicholas through the Ages”

[…] Saint Nicholas through the Ages (foundinantiquity.com) […]

Why would the butchers have made him their patron saint? What, did he make sure that the baker got a fair trial? Was it to keep him quiet? It didn’t work!

Ah, I forgot to tell the end of the story of the butcher. In some versions of the tale, when Nicholas revived the children, the evil butcher was struck by his own sense of guilt and asked for forgiveness. Nicholas received his confession and forgave him. And so Nicholas was considered a patron saint of penitent murderers, as well as of butchers.

[…] in a little reality? There’s some background on the actual St. Nick here and more on […]

[…] Nikolaos 3 Çocuğu Diriltiyor […]