For years I’ve been trying to get myself to read through the whole of Homer’s Iliad from start to finish. And lately I realised how to do it in the most painless way possible: I plugged in my earphones and listened to an audiobook of Homer’s Iliad on my half-hour daily bus rides to and from work. I was all the way through in about a month or two.

Listening to Homer on audiobook worked well for me, and I strongly recommend you take advantage of this audiobook format. As Classicists we’re prone to take reading for granted as the default method of absorbing literature. But it is good to remind ourselves that Homer’s great epics were probably passed down orally for centuries before they hit pen and ink. And even in the Classical and Hellenistic periods, most Greeks would have considered listening to be the default way of experiencing Homer, and would not have seen the Iliad or the Odyssey primarily as ‘books’ to be read silently off the page in your head.

But listening to Homer on audiobook does not just give you the fun of feeling more authentic. It offers a better aesthetic experience, too. As I will explain below, many of Homer’s characteristic literary devices are much better suited to the aural format than to the print book, and so listening to Homer rather than reading him gives you a better appreciation for Homer’s art.

I want us to step back for a moment, and think about what it feels like to read the Iliad or the Odyssey from a print book.

When you read a book, you have to bring yourself through it. It doesn’t read itself. And so if the book starts to drag, your reading speed starts to drag with it.

Unfortunately, many of the most strikingly Homeric literary features seem fiendishly calculated to make the books drag. The metaphors are long, the lists (particularly the Catalogue of Ships) are long, an ekphrasis or description of an artwork can be very long indeed. For most of the Iliad, Achilles is not fighting with the Greeks, but the story faces a multitude of diversions upon diversions. Why, indeed, does even the wayfarer whom Hermes impersonates – and who does not appear in the epic himself – have a long and noble family history that must be recalled? All of this needs to be ‘ploughed through’ if you read Homer, and the more you feel burdened by the work, the harder and slower your progress becomes.

The book format itself can also encourage you to think in terms of ‘how much is left before I’m done?’ and thus to be more prone to impatience with Homer. When you first open a book, you have a tiny amount of paper in your left hand and a huge amount in your right hand. At every moment, by glancing at the position of your bookmark, you can see how far you’ve progressed and how much thickness is still left in the book. You can flip forward to check how close you are to the next arbitrary book division, and the sight of white space at the end of a book exaggerates the importance of this later Hellenistic division scheme. The print book is very different in feel to the original character of the epic, and it encourages you to try to keep up the pace and skim when you feel like you’re lagging too much. Lagging and skimming both, of course, do injustice to Homer and together they make his sentences seem choppier.

The audio format offers a very different physical experience. I plugged in my headphones and let the narrator do his thing. No page turning. No idea of the thickness of paper left in my hand, and very little clue as to how much playtime was left, since it was broken up into so many tiny unnamed tracks. There was no possibility of skimming or rushing or lagging through Homer, but the narrator kept to a reasonable pace. I didn’t need to eyeball the page and read the same sentence three times. I could close my eyes and rest my head, while letting the sweet words of Homer wash over my ears.

I could listen to Homer in dim light on the bus at sunset, as the sky grew dark overhead and evening set in. There is something enchanting about hearing Homer, the blind bard, whisper in your ear out of the dark. This is a rather different feeling from being hunched over a printed textwall.

The most important difference between hearing the audio and reading the printed text, however, was that when I listened, I had no idea what was coming next. When you look at text on a page, your peripheral vision gives you some clue of how long the sentence or paragraph (if it is divided into paragraphs) will continue. But when you listen to the Iliad or the Odyssey on audio, every sentence, every metaphor, every episode expands as you wait in anticipation for it to reach completion. I found myself often hanging on the narrator’s words, in a way that I hardly ever feel when I read any classical work in translation.

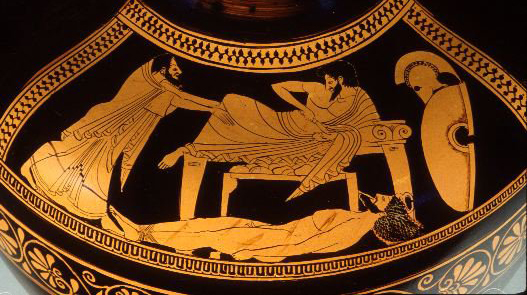

What I found particularly entertaining was the description of the Shield of Achilles in book 18 of the Iliad. (When I wrote this down, I had to look up what book it was in, because book divisions didn’t really stick in my mind while I was listening to the audiobook.) I had previously read a similar, though different, ekphrasis on the Shield of Aeneas in Vergil’s Aeneid book 8, so although I didn’t know the exact details of Achilles’ shield, I knew that once Homer started describing the shield he was probably going to take his time. Sure enough, the epic description lengthened out as Hephaistos wrought scene after detailed scene onto this shield. But as I listened to it, I actually found it very amusing trying to picture each eclectic scene, scratching my head about how all this art could fit on the shield, while in the meantime the narrator went on to elaborate yet more improbable scenes on top of the last. To me, this was Homer revelling in his own cleverness, spinning out a Tall Tale that gets ever taller with each passing word. It was a masterwork of tale crafting, and I was hooked.

I also found that hearing Homer narrated by a real human voice was particularly important for my first total run-through of the Iliad. A human narrator gives each word the right intonation and stress, which clues you in on how the various parts of the sentence fit together when sentences get long. When you read blind, you have to guess the right word stress as best you can, and sometimes you get it wrong – particularly when phrases get separated by line divisions in printed text.

Once you’re somewhat more familiar with the text, you are much less likely to misread a printed translation, and you can read different translations in all formats to let the epic grow on you. It’s similar to how a good piece classical music grows on you with each different hearing. It just so happens that from my experience, the easiest way to get through the initial tentative stage of ‘reading’ the Iliad or the Odyssey for the first time was to eschew the printed book and take in the masterpiece through the ears.

Because honestly, the truth of the matter is that Homer grabs you by the ears. The worst of Homer’s vices – his tendency to lengthen out his descriptions, his tendency to divert the narrative – become hooks that intrigue you and draw you into the tale, if you listen to him with keen anticipation. The Iliad and the Odyssey were never made for print. They were made for listening.

5 responses to “Homer grabs you by the ears”

“But it is good to remind ourselves that Homer’s great epics were probably passed down orally for centuries before they hit pen and ink. And even in the Classical and Hellenistic periods, most Greeks would have considered listening to be the default way of experiencing Homer.”

I had a language arts teacher in high school (also the director of all of our school plays) who insisted that “plays are meant to be read out loud.” So when we did Othello so we could discuss it in advance of the school’s production of Othello, we assigned parts and read it out loud as a class rather than being assigned portions of the play to read at home.

In reading this, I am reminded of why – certain works are designed for one medium or another, and it’s easier to appreciate them if you experience them in the medium they were designed for.

I couldn’t agree more! I loved reading Shakespeare aloud in class back when I was in high school. We’d have to put ourselves in the drama, and it really made a difference to how we appreciated the bard’s artful skill.

I love listening to classics on audiobooks. Especially when chasing my kids around at the park.

Have you ever listened to Dan Carlin’s hardcore history? It’s not an audiobook, but it’ll make your next couple dozen or so of your commutes more fun.

I get here from a Google search on pompeii linear perspective, and you answer a question that had been burning since art history class. So here I come to this article which I was hoping would have a link to Amazon or Audible so as I can get you some money. Hell, I thought it was specifically tailored to get me to do that.

And nothing! Step up your game, son!

I’m glad you liked my article on linear perspective on Pompeian wall paintings. And thanks for recommending Dan Carlin’s hardcore history podcasts – I hadn’t heard of them before, but they look very interesting.

Haha, and no, I didn’t put a link to Amazon or Audible on this article. Mainly because I felt like I hadn’t properly tested out the myriad versions of audiobooks on Homer’s epics to find the best version, and testing them all out would cost me money. I listened to the Fitzgerald translation of the Iliad narrated by George Guidall, and I enjoyed the narration overall. But at times I found Guidall’s voicing of female characters to be a bit irritating. (Here some links to that version: http://www.amazon.com/The-Iliad-Fitzgerald-Translation/dp/B00HUWGEU6/ref=tmm_aud_title_0?_encoding=UTF8&sr=&qid= and http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/iliad-a-homer/1001823263?ean=9781402558207)

This is a really excellent suggestion. I think so much in terms of reading the written word silently on a page that it’s never occurred to me to listen to Homer. I too have found it difficult to plow through the whole of the Iliad. The most lively experience of the work that I’ve had was in Greek class when we did Homer, which was certainly engaging partly because of the read-aloud element (as well as the community and the original language). I think I must get an audio version of the Iliad now as well. It makes a lot of sense to experience the work aurally.