There’s an art to translation. It involves moving concepts from one language into another while trying to refit the same thought into a different set of grammar rules. In this study I’d like to look at one obvious part of the translation process: word order change. In studying this, I don’t mean to suggest that the inevitable changes in word order are necessarily bad or represent the degree to which information is lost in the act of translation. Quite the opposite. Where it is needed, the word order should change so that the meaning can be properly conveyed. Otherwise, there would be no point in translating anything.

What I want to investigate is how much the word order changes when translating a passage from Ancient Greek (specifically Koine) into various other languages. For instance, how closely can a Latin translation mirror Greek word order? Are Romance languages any closer to Greek word order than Germanic languages? Was medieval English more similar to Koine Greek syntax than contemporary English? And roughly how close is Modern Greek to its ancestor?

In this study, I’ll explore how much word order change occurs in several published translations of the same Koine Greek sample text, analysing eleven translations spread out over six languages: Latin, English, German, French, Mandarin Chinese, and Modern Greek. What I like about studying word order is that it’s a fairly obvious part of the language and you can see it move around. This is not a subtle study about ineffable shifts in semantics. It’s a crude, chunky experiment looking at how blocks of data move positions in different languages to express more or less the same thing according to different syntax rules. Although the sample text is short, at least this exercise can give a taste of how similar and distant the various languages are to Ancient Greek in this particular respect.

Methodology

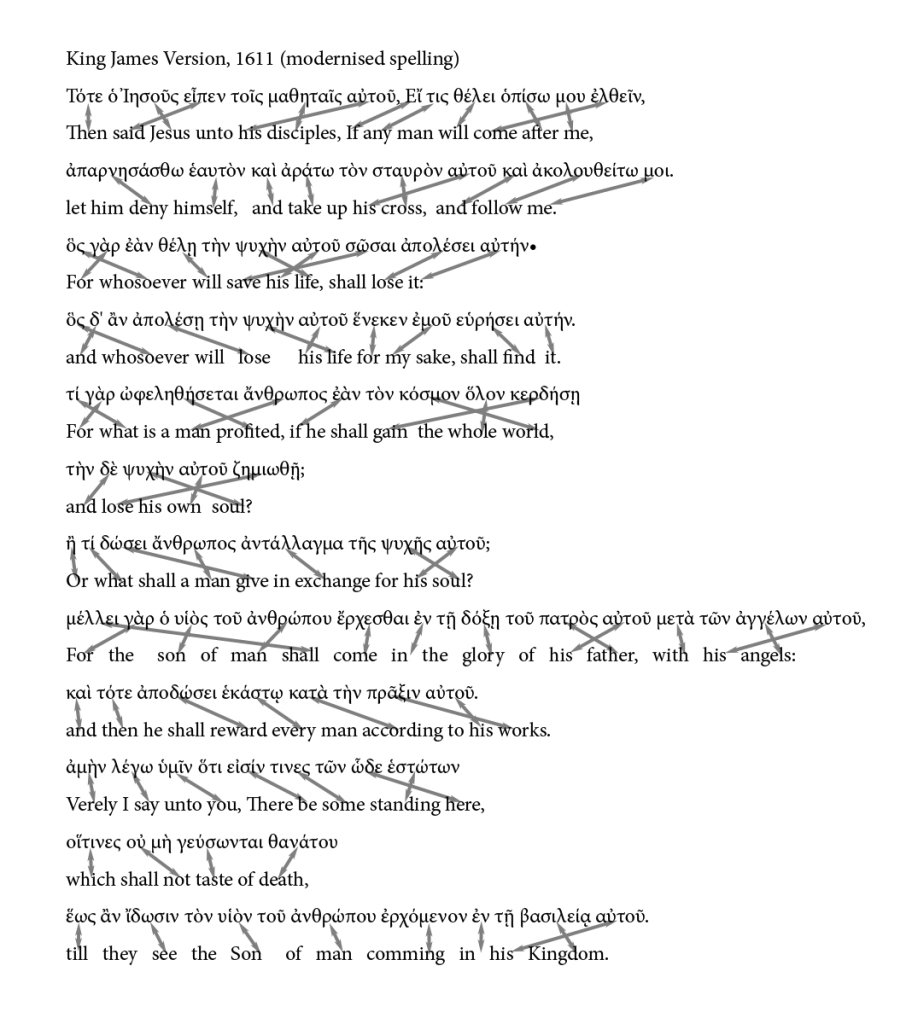

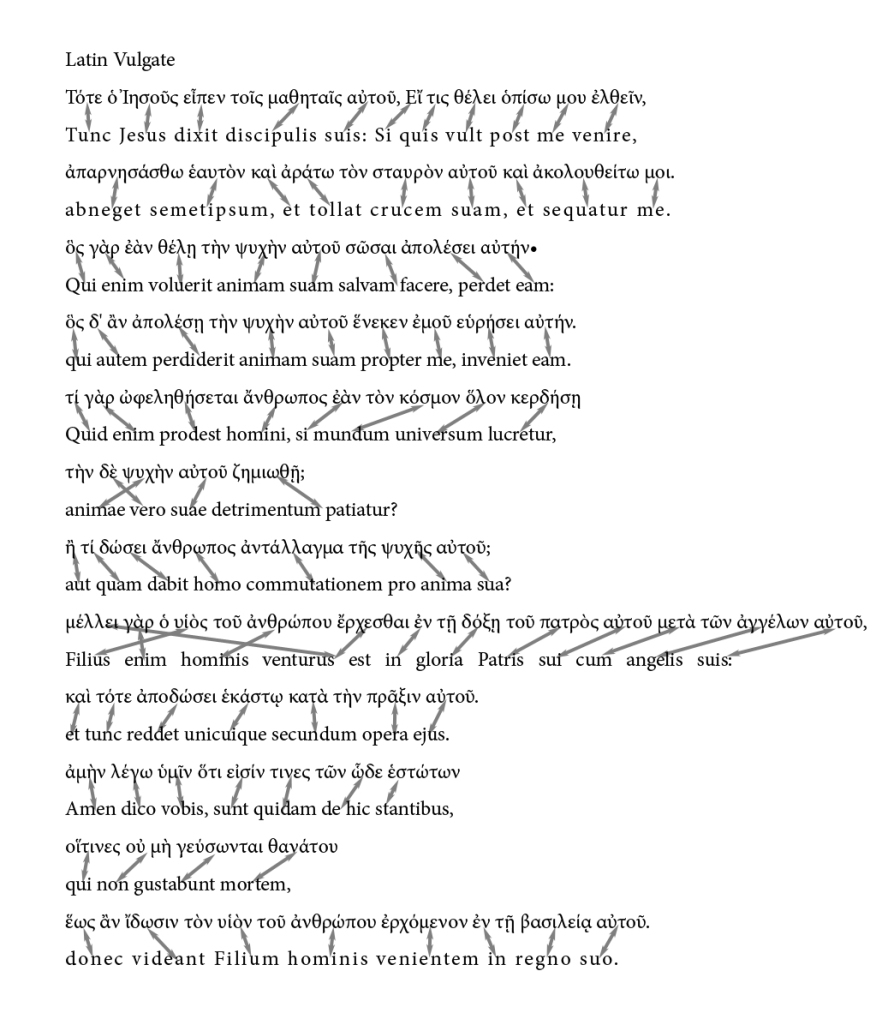

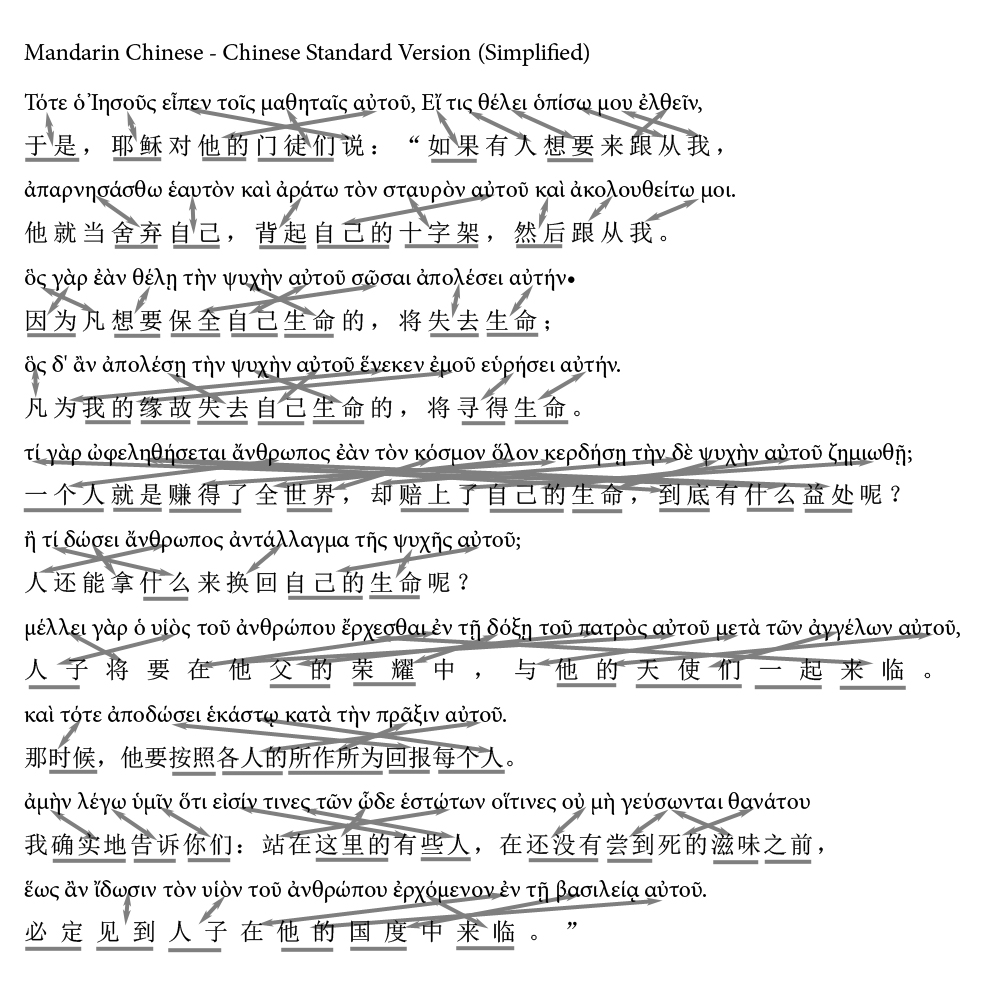

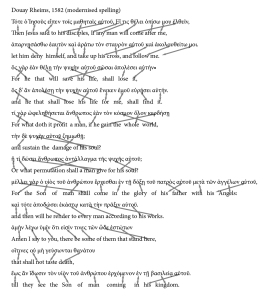

The premise and method is very simple. I found a Koine Greek text which has been translated very carefully many times throughout history into many different languages. The most convenient choice was, naturally, a passage from the Greek New Testament, Matthew 16:24-28. Where possible, I tried to find translations which were more formal and “word for word” rather than “thought for thought”, although in practice all readable translations are to some extent “thought for thought” since truly mechanistic translations (interlinear translations) can’t really convey the sense of the passage for anyone who does not already know the rules of Greek. I placed the original Greek text just above corresponding sections of the translation, and drew a line from word to word (I ignored little words like “the,” which functioned differently in different languages or were absent altogether). Clusters of crossed lines indicate a change in word order.

To measure how much word order has changed, I counted the total number of clusters (that is, how many groups of crossed lines there were) and the total cluster length (the combined total number of lines in all clusters).

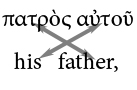

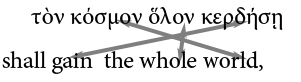

For example, the cluster below would count for a length of 2:

Whereas the cluster below would count as a 3:

And this other cluster would also count as a 3:

It is a rough method, but at least it can be applied with relative consistency. The reason why I found it was misleading to count only the number of clusters (and not their length) was that once the scrambled-ness of word order passes a certain point, the number of clusters in a passage actually decreases as several clusters are absorbed into each other. My solution of counting the total length of clusters is not a perfect indicator of the amount of word order change, but at least it doesn’t decrease when word order change is at a maximum.

It wouldn’t be as relevant to count the total number of words displaced, since this would penalise languages with larger amounts of short words more than others.

Translations of translations

Partway through this study, I realised that a couple of my translations were translated from the Latin Vulgate instead of directly from the original Greek. Rather than discard the data I’d collected, I included a couple more translations from the Latin and compared them to translations from Greek to see if there was any significant difference in word order shift. The results are all analysed below.

However, I will make one final word of warning before we dive into the study. While I am using Greek word order as a standard of measurement, we should not think less of a language because it is not as similar to Ancient Greek as another language. It is surely unfair to judge a modern language for not being something it isn’t. It probably doesn’t need to be said, but being less like Greek doesn’t mean that the language lacks its own kind of complexity or subtlety of expression.

Results

I compared 11 translations in total from 6 different languages. The results are in the table below; the lower the numbers, the closer the translation word order is to the Koine Greek word order.

| Translation | Source language | no. of clusters | total cluster length |

| Latin Vulgate | Greek | 2 | 7 |

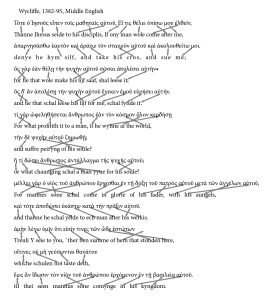

| English – Wycliffe | Latin Vulgate | 19 | 45 |

| English – Douay-Rheims | Latin Vulgate | 18 | 43 |

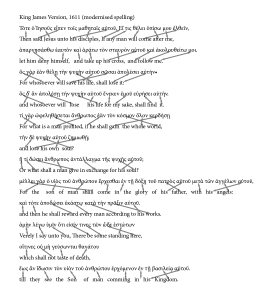

| English – KJV | Greek | 20 | 46 |

| English – ESV | Greek | 16 | 43 |

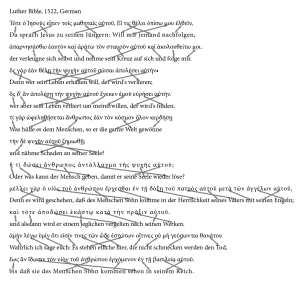

| German – Luther | Greek | 22 | 53 |

| French – de Sacy | Latin Vulgate | 21 | 50 |

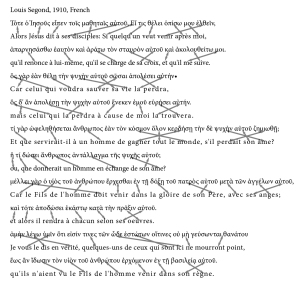

| French – Louis Segond | Greek | 20 | 47 |

| Mandarin Chinese – CSV | Greek | 15 | 58 |

| Modern Greek – Demotic | Greek | 13 | 32 |

| Modern Greek – Katharevousa | Greek | 8 | 18 |

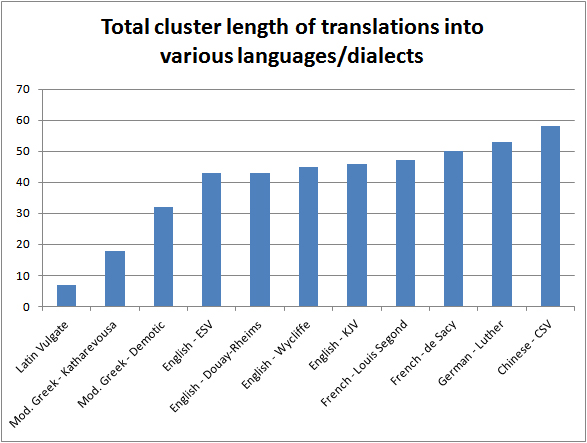

The graph below orders these translations by total cluster length (that is, the sum of all lines crossed in all clusters):

Far and away, the Latin Vulgate translation (based largely on Jerome’s translation project compiled in the 4th century AD) had the closest word order to the Greek. I mean, just look at this diagram below. There were only two clusters in total; the rest of this translation was a straight out substitution of words for other words.

Of the clusters that did occur, I’m hesitant to even call the first one a change in word order, since in the first cluster the Latin vero (“indeed”) is actually in the same post-positive position as the Greek δέ – the only reason for the word order change here is that Latin lacks the definite article (“the”), so for vero to be post-positive it must come after animae. The second change in word order is the result of resolving the future paraphrase μέλλει… ἔρχεσθαι (“will…come”) into the Latin future paraphrase venturus est, which needs its two parts to be very close to each other. This μέλλει + infinitive future phrase seems very peculiar to the Greek and needed to be rephrased in almost every other language translation as well.

Latin and Ancient Greek are surprisingly similar in basic grammar. Historically they came from different groups of the larger Indo-European language family, and various Greek and Italic-speaking cultures were geographically separated for thousands of years. Despite this longstanding cultural separation, the inflectional system in both languages is very similar. When I started learning Ancient Greek for the first time after many years of Latin, I did feel like the first half of the grammar course was a just Latin with different vocab, and a word for “the”. (The later, more complex grammar lessons were very different though.) This trend seems to reinforce the idea that Latin shares a lot of basic similarities with Ancient Greek.

On the other end of the scale, the Mandarin Chinese translation (Chinese Standard Version) exhibited the greatest amount of word order change… so much, in fact, that one sentence in the middle seems to have been completely rearranged, even clause by clause.

This makes sense, since Mandarin Chinese is extremely different from Koine Greek and Latin. While Greek and Latin nouns and verbs are highly inflected (the endings tell you what the words are doing), Chinese has basically no inflections whatsoever and the critical information about subject, verb and object is conveyed wholly by their position in the sentence. In this sense, Chinese is rather like English except with even more emphasis on word order. There isn’t even a plural for most nouns in Chinese (the exceptions are nouns which denote “people”) and none of the verbs possess markers for person or number. Various little words can modify the tense of the sentence but they are not the same as inflections.

Given that the rules of syntax are so different between these two languages, it’s no large surprise that Greek word order had to change considerably to fit idiomatic Chinese expression.

Looking back at the graph, it seems that most of the modern languages in this sample needed a similar amount of rephrasing to preserve meaning. I was surprised in particular that the English translations of vastly different ages – ranging from the Wycliffe medieval translation of 1382-95 to the King James Version of 1611 to the modern English Standard Version of the 1990s – varied very little in their amount of necessary rephrasing. English, it seems, was never really much like Greek, or at least not since Middle English came on the scene (Anglo-Saxon translations of Matthew are not yet available online). There also did not seem to be a strong difference between the amount of word order change in a Romance language like French compared to that required of the Germanic languages, English and German.

I also found there was very little difference in word order change between versions which were translated from the original Greek or Latin Vulgate. The English Wycliffe and Douay-Rheims and the French de Sacy translations were retranslated from the Latin Vulgate, whereas the English KJV and ESV and the French Louis Segond were done from the original Greek. This doesn’t seem to have significantly affected their scores for word order change. It’s not all that surprising in the end, since the Latin appears to have almost exactly the same word order as that of the Greek.

Of all modern languages, the dialects of Modern Greek appear to be the closest to Koine Greek in word order. That is understandable, since Modern Greek is ultimately descended from medieval, Koine and Classical Greek. However, there is a very strong disparity between the different ends of the Modern Greek spectrum. Greek as it is spoken today exists on a continuum from the more sophisticated literary dialect on one end to a form of common and everyday speech on the other end.

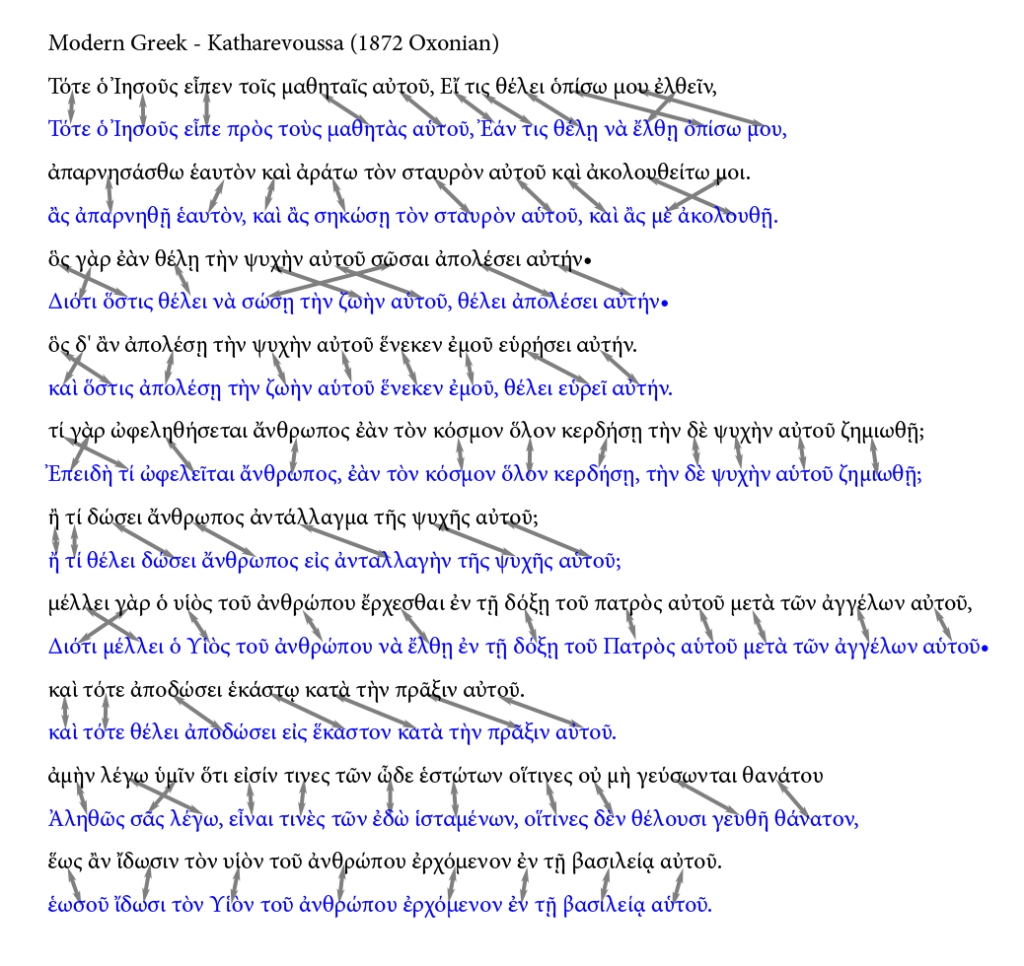

The “purist” Greek, or Katharevousa is sometimes considered artificial and is associated with officialese. Others see proficiency in Katharevousa as a sign of good education and appreciation of high literature. This 19th century translation into Katharevousa is only partly rephrased from the source language and large sections of the translation seem to have been left untouched by the translator.

I changed the colour of the recipient language to blue to make it easier to work out visually which language was the original:

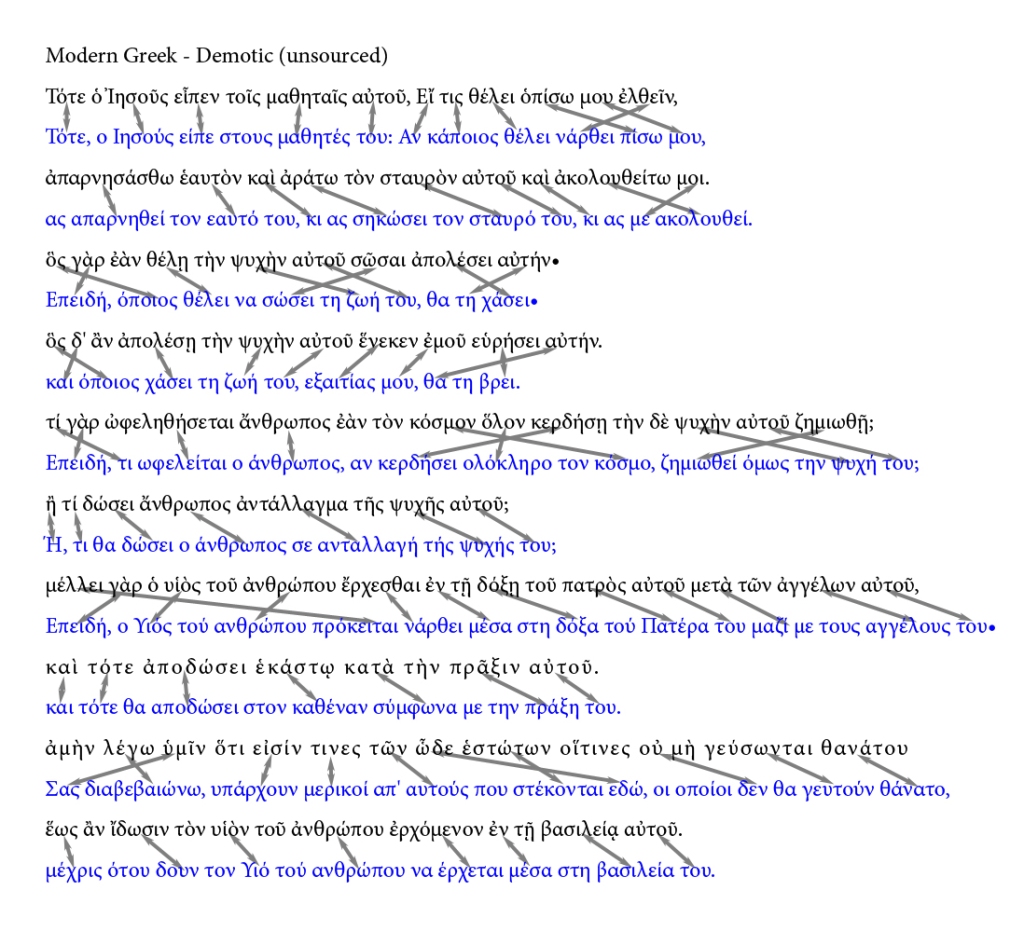

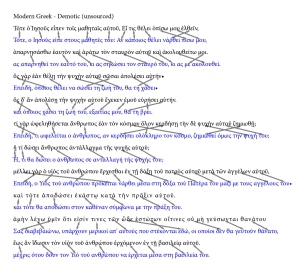

Demotic Greek, the kind of Greek spoken commonly by the people, is rather more rephrased from Koine than the Katharevousa, but it is still somewhat less rephrased than most other modern languages:

Katharevousa appears to straddle the gap between Koine and Demotic Greek, and a person familiar with Katharevousa is said to be able to figure out passages in Koine, especially if they had learned basic lessons about Classical Greek grammar at some point during their schooling. But Demotic and Koine are mutually unintelligible. Classics and Theology students definitely cannot read Modern Demotic Greek, and Demotic speakers cannot understand full sentences of Koine.

Conclusions

In a sense, translation is the act of moving something from one place to another – in regards to most languages this will literally mean that words must be moved around. If less is done, the job of the translator is incomplete. What I find astonishing is that Latin, despite being only loosely related to Greek, can replicate Koine Greek syntax so well that it is nearly possible to create a structurally “word for word” translation when moving a sentence from Greek into Latin. In fact, 4th century Latin seems to be more similar in word order to Koine Greek than the Modern Greek dialects are.

There are so many ways that this study could be expanded. I feel that I’ve only scratched the surface with my very small sample passage and my limited selection of recipient languages. I would really like to add more Romance languages to the study like Spanish, Italian and Portuguese, and even Romanian (which is said to be the grammatically closest to Latin). I’d also like to include other highly inflected languages like Sanskrit and Russian. Currently Mandarin Chinese is the only non-Indo-European language involved in the study, but it would be great to include Syriac at some point, to get a better sense of how languages outside of the IE language group may differ from those inside. Or I could redo this study with a much larger selection of English translations, old, new, formal and dynamic, and lay them all out on a scale of how greatly word order changes between these translations. The preliminary findings seem to suggest that English translations are not all that different from each other in the amount of word order change required, so separating them out might be tricky and require larger sample passages.

In any case, I hope you enjoyed working through this experiment as much as I did.

Appendix

For full disclosure, I know English, Latin and Ancient Greek. I studied Chinese for about 7 years before giving it up in year 10 and focusing on Latin, because Latin was much easier to learn. I can still remember parts of Chinese, though doing this exercise reminded me of just how unforgiving that language is. My current grasp of German and French is quite basic (but happily I am due to start formal German lessons in a couple months time). My understanding of Modern Greek is limited to how much it resembles Ancient Greek, which is not a whole lot. Luckily, the premise of this experiment was not to study the subtle aspects of word-meanings but the very obvious feature of word order. I relied mostly on checking online dictionaries to establish which translated words were meant to represent which Greek words. If I have made a mistake in any of these transcriptions, I would welcome you all to comment below.

In order of lowest total cluster length to highest:

4 responses to “Moving words: which languages have the closest word order to Ancient Greek?”

[…] Moving words: which languages have the closest word order to Ancient Greek?, Carla Schodde, 2013 […]

[…] langues grecques (sur l’excellent site de Jacques Leclerc, pour le passage sur la katharévoussa) Moving words: which languages have the closest word order to Ancient Greek?, Carla Schodde, 2013 Du gaulois dans la langue française ?, émission web de Romain Filstroff […]

[…] Moving words: which languages have the closest word order to Ancient Greek?, Carla Schodde, 2013 […]

Dear Carla,

Thank you so much for this wonderful information. I particularly enjoyed your study on translations. I certainly have a greater appreciation for Latin now!

I am currently writing an introduction for the book of Romans for Chinese speakers. I came across your web page while searching for material that would illustrate why we must first strive to understand the author’s original meaning if we are to apply it to our daily life. Your work clearly shows the vast differences that exist between Greek and Chinese.

Thank you again,

Jacob Lee