Some of the types of assessments Latin teachers have been traditionally setting are quite weird, the kind of things that aren’t normally done in any other languages. Consequently, it is hard to find recent research on whether what we are testing really matters.

Perhaps one of the strangest things we do is Grammar Analysis, where a student is asked to remember the “ablative of this” and the “genitive of that”.

A year or so ago, there was an alarm among Victorian Latin teachers when (due to an unfortunate miscommunication from the writers of the curriculum) we thought that Grammar Analysis would be completely removed from the new Year 12 Latin study design. At the time, we reacted quite defensively. We attended a consultation meeting with the curriculum committee where we went around the table repeating all the same things: that we needed Grammar Analysis in some form in the year 12 study design, because otherwise we would lose the rigour of the subject, students wouldn’t bother to learn grammar at earlier year levels, and the quality of unseen translation would drop.

It was a drama and half, and I shouldn’t say more about the episode, except that we got what we asked for and Grammar Analysis (“questions on accidence and syntax”) was prominently reinstated into the Year 12 study design.

But, was Grammar Analysis really the right hill to die on?

The new Victorian Latin study design gives leeway for how deeply teachers want to teach Grammar Analysis, as it is only internally assessed. How much should we emphasise Grammar Analysis among our students? How useful is it to be able to identify a subjective vs. objective genitive, or a dative of person judging, or a circumstantial participle?

For better or worse, the skill we care most about in Victorian Latin is the unseen translation. It remains just under half the marks of the final year 12 exam and is one of the best discriminators of student performance in the subject.

I decided to look into the assessment data of my year 10-12 students in the years 2018-2021 to see what metrics are the closest predictors of success in unseen translation.

Limitations

Some limitations with my study are that correlation does not equal causation – I expect at least some of these metrics will align to unseen translation without actually helping translation, because relative levels of diligence and motivation would cause the same students to do well in all hard assessments. If I plotted how the students did in Maths, it would probably correlate somewhat to how they did in unseen translation. That wouldn’t necessarily prove that skills in Maths help students translate Latin.

What this study might show, however, is a relative lack of correlation. If we expect a type of test to legitimately test student’s language skills, then we expect it to correlate with their ability to translate unseens. If we see a scattershot, perhaps we are not really measuring language skills that students use in the unseens.

A further limitation is the size of my sample. The number of data points in comparing performance within the same year was 41 (eg. John in year 10 vs. John in year 10, John in Year 11 vs. John in year 11), and the number of data points for comparing performance from a previous year to a following year was 24 (eg. John in year 10 vs. John in year 11, John in year 11 vs. John in year 12). Only 17 unique students made up the three cohorts graduating year 12 in 2019, 2020, and 2021, and there was some attrition as students moved schools during this time.

However, a positive of this data set is that all the students had the same Latin teacher the whole time (myself), and the way the assessments were taught and marked and their relative difficulty was consistent year on year.

With all this, let’s see what test scores appear to correlate most strongly to high scores in unseens.

Previous performance on unseen translation

In the graph above, I plotted the average unseen translation scores for the same student in two consecutive years. The horizontal axis represents average unseen scores in one year, and the vertical axis represents how well they did the following year.

This is a bit of an obvious point, but being previously good at unseen translations is a really good predictor for how good you’ll be at unseen translation in the future.

The Multiple R value for this correlation is 0.7243 – the tightest correlation of all the data in my study. (a value of 0 would indicate no correlation, a value of 1 would indicate strong correlation.)

Other types of assessment

The main other types of assessment (excluding seen translation) we typically do in high school Latin include:

- Grammar Analysis

- Vocabulary tests

- Oral assessments

- English to Latin translation

Grammar Analysis

In Grammar Analysis, students identify accidence and syntax in seen or prepared texts. Questions can include:

- What case is this noun, and why was this case used? (eg. Posessive Genitive)

- What is the person, number, tense, voice, and mood of this verb?

- What use of the subjunctive is exemplified by this word?

- What part of speech is this word?

- What word does this adjective agree with?

In the first graph, I plotted how well students did in Grammar Analysis (GA) versus their unseen translation scores in the same year. In the second, I plotted their previous GA score versus their performance in unseens in the following year.

Both graphs exhibit a very wide scatter. A student in the same year could get 100% in GA but less than 85% in unseens, or conversely, they could get 90% in unseens but 60% in GA. (Multiple R = 0.4039)

Moreover, the correlation between doing well in GA one year and then doing well in unseens the next year is even weaker. (Multiple R = 0.3646)

GA does not appear to be a good predictor of success in unseen translation, especially in future years.

Anecdotally, I think all Latin teachers have experienced students who show conflicting results in GA and unseen translation. When a student comes along with great instincts at reading Latin in context but does rather woefully at remembering the Ablative of Something, we worry that all the missing information about grammar categories is going to trip them up in translation in the future, so we might advise them to work on that weakness. Conversely, when a student is doing brilliantly at GA but can’t apply the rules in translation, we might have advised them to re-read their grammar notes on such-and-such that they missed in the unseen, because they seem to respond well to explicit grammar instruction when they do GA. I’m not entirely convinced that these approaches are helpful.

If Grammar Analysis is so vital to good unseen skills, it is not clearly indicated as such by my student data.

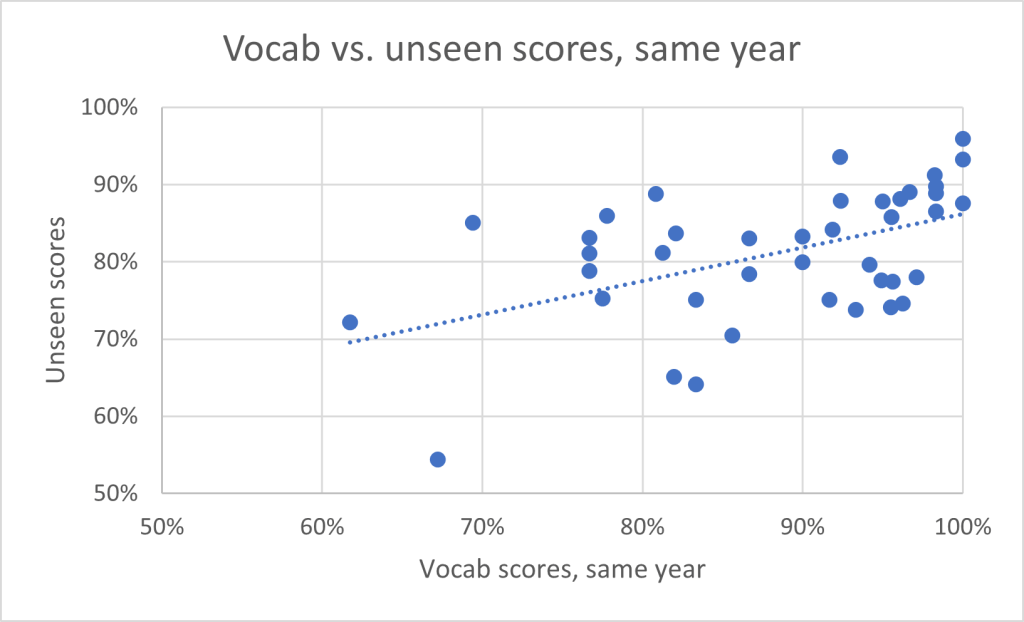

Vocabulary

In this study, I only included vocabulary testing where it was in the traditional format of “provide one definition for this word”. The direction is always Latin-to-English. At year 10 level, I use the 20-word chapter vocab lists that come with my textbook series, but my vocabulary tests at year 11-12 level draw from very long lists of Latin words in order of frequency. For example, 100 word test is drawing from the top 100 words in Latin, the 200 word test is from the top 200, etc.

Students in these cohorts have learned lists up to 500 words long.

The typical method for learning the vocabulary is through online flashcards such as Education Perfect or Quizlet, where students write or select single English meanings for each Latin item.

Single-item vocabulary tests like these have only a slightly stronger correlation to unseen translation performance than GA scores. The scatter is very wide, especially at the lower end of performance.

I was expecting vocabulary testing to correlate strongly with “diligence” or “motivation” and thus be at least somewhat closely correlated to unseen translation skills, but it seems that being able to do well on a vocab test is not a great predictor of unseen translation performance.

In my experience, when students encounter their vocab words in a real sentence, they have trouble making the right decisions as to what meaning that word should have in its context. I tend to be pretty lenient on vocab tests and allow them to just state one meaning of the word, but in an unseen translation, some meanings are definitely more appropriate than others. An additional difficulty is that students see vocab words in “dictionary format” (with all their principal parts) in vocab tests, but need to be able to recognise them in inflected forms in an unseen. When I experimented with giving vocab tests with inflected forms of the words students were learning on the lists (eg. cēpit instead of capiō, capere, cēpī, captum), vocab scores dropped by about 50% compared to traditional tests.

Having a large vocabulary is extremely important to being able to fluently read any piece of writing. However, single-definition traditional vocab tests do not very accurately capture a student’s ability to recognise vocabulary in a translation.

I am currently looking into better ways of encouraging the development of vocabulary that responds well in context. Some of this includes experimenting with picture vocab lists where students must answer a question out loud in Latin which contains the target vocabulary feature.

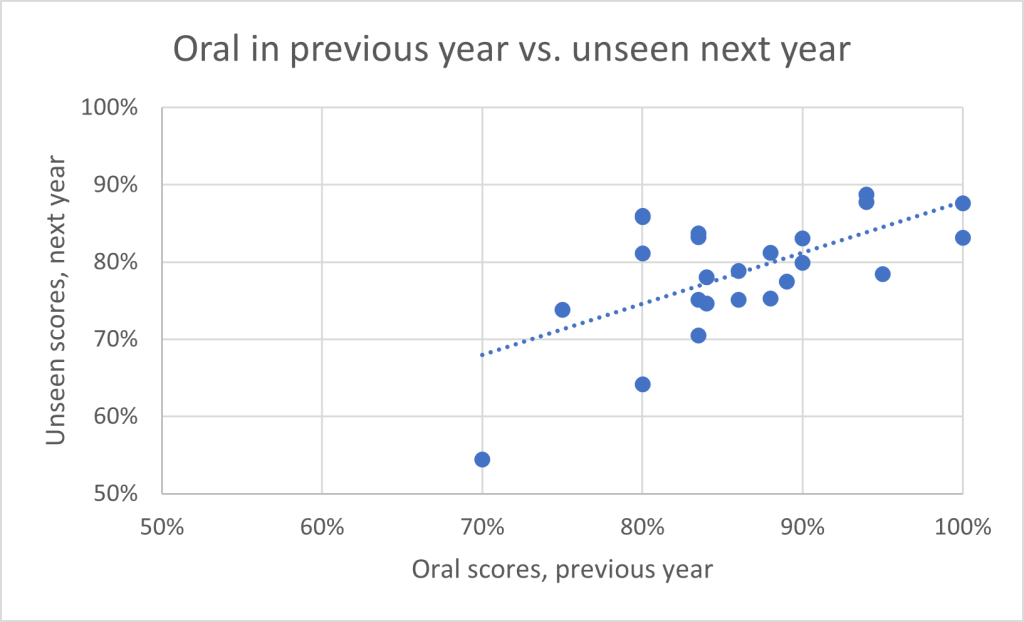

Oral

My oral assessment involves getting the student to read aloud a passage of Latin, with attention to accuracy of pronunciation as well as dramatic expression. I mark students on a rubric containing five criteria: consonants, vowels, accentuation, fluency, and expression. During Covid years (2020-2021), I required students to create voice recordings, but during pre-Covid years, I listened to them perform individually.

The oral assessments were essentially just testing pronunciation, with a bit of performance flair thrown in. It was not a communicative task in the sense of simulating a live conversation in Latin.

Students were given oral assessments in years 10 and 11, but not in year 12.

Scores in oral assessment were not good predictors of student achievement in unseen translation within the same year, but intriguingly, they were somewhat correlated with unseen translation in the following year. (Multiple R = 0.6114)

Why might a student who did well on an oral one year not get the benefit of that oral in the same year but have a lag-time when they would do better on translations the next year?

I’m speaking speculatively, but it would make sense that good pronunciation might have a positive effect on contextual vocabulary acquisition.

If a student worked hard to improve their pronunciation before an oral assessment, in theory they would spend the rest of the year reading Latin with a clearer sound assigned to the words. In addition, the effort of making their performance more dramatic would involve thinking carefully about how words should be naturally grouped together into phrases, which would help in later recognising phrase boundaries in readings.

The cumulative effect of having better pronunciation could be improvements in reading that eventually improve their unseen translation abilities.

I say all this knowing that my oral assessments are quite limited in scope and my data is still pretty fuzzy, but it makes me stop and think about the significance of oral assessments if they have more of an impact on the next year’s translation ability than last year’s vocab tests and GA scores.

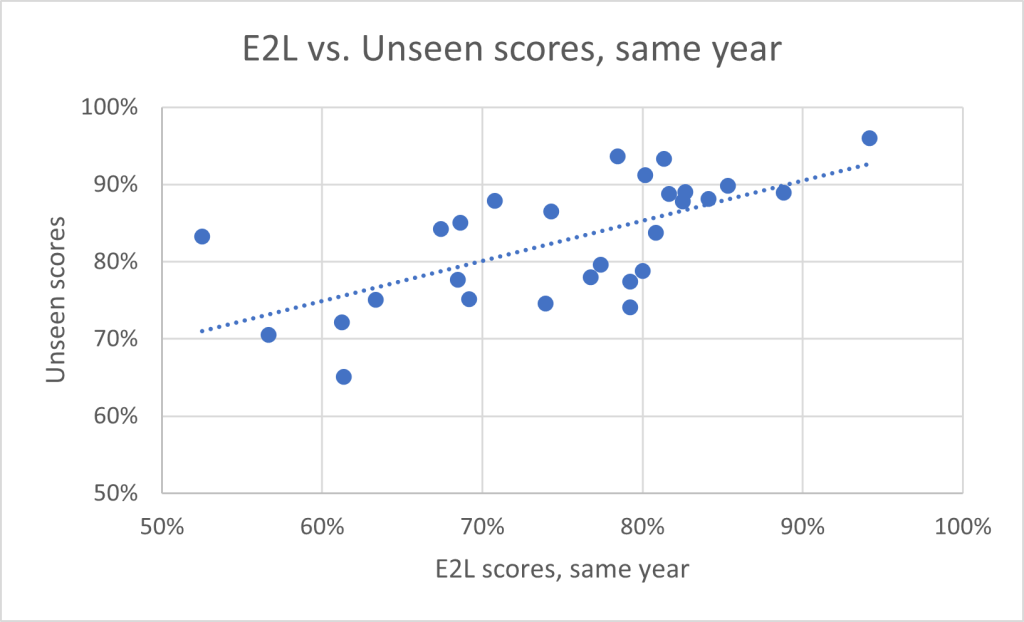

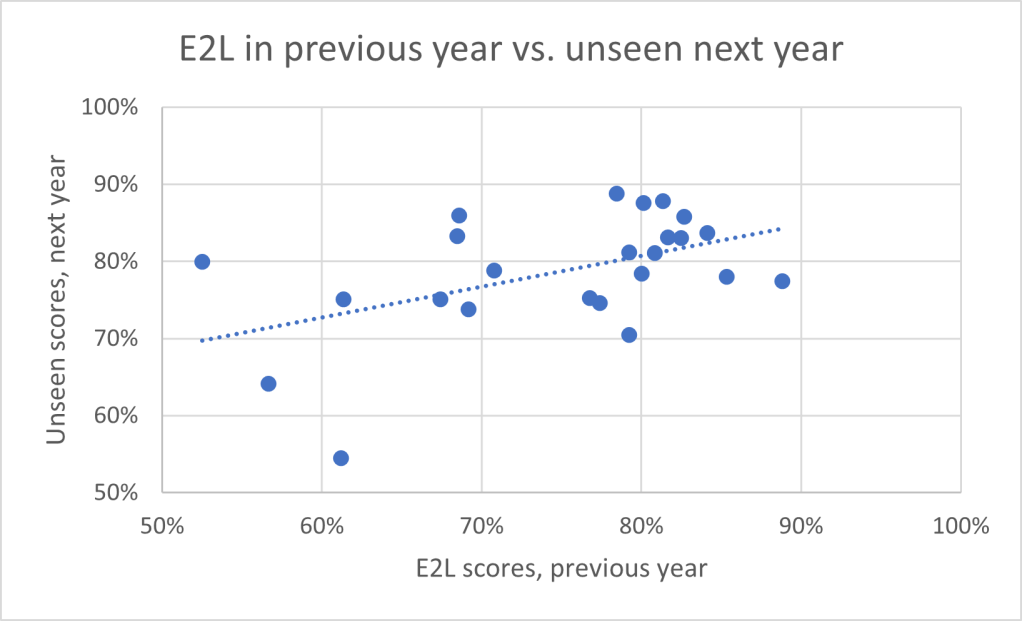

English to Latin translation (E2L)

Students are presented sentences in English which they must then accurately translate into Latin. The most common errors involve adjective agreement, but often there are little rules like “this verb takes the dative not the accusative” that continually pop up. Ambiguity in English is often a source of angst – should you use “suus” or “eius” for “his”? It is also brutal if students haven’t completely internalised all the types of clauses, such as which ones use the subjunctive and which ones use accusative and infinitive. This is a high-stress assessment to pretty much all students.

Students were tested on E2L in years 10 and 11, but not in year 12.

English to Latin translation (E2L) is legitimately a very challenging task. Unlike a vocab test or a grammar analysis, simple rote-learning will not cut it here. This test cannot be brute-forced with memorisation: similar to unseen translation, it requires students to really, really know their stuff.

Interestingly, E2L scores are relatively strongly correlated to unseen translation within the same year (Multiple R = 0.6522) but not as strongly correlated to the unseen skills for the following year (Multiple R = 0.4901).

I can speculate as to why the E2L didn’t have as strong a correlation to the following year’s unseen translation progress. The last E2L test my students ever face is in the first semester of Year 11, and it typically excludes some final pieces of challenging grammar such as conditionals and gerundives. While studying for their final E2L, they work hard on consolidating previously learned grammar structures such as the uses of the subjunctive, and the accusative and infinitive phrases. This is very useful to the unseen translations in year 11, which are typically a bit easier than the year 12 unseens. As unseens get filled with harder grammar not covered by their final E2L test, the correlation between how they did back then and how they do with the last pieces of grammar becomes weaker.

That may be one possibility among many. I don’t quite know what is going on, because it could also be possible that E2L is a really good measure of the same qualities (diligence, motivation) that produce students with good unseen skills. It could also be a measure of their internalisation of the Latin language, or conversely their ablity to consciously apply learned grammar rules.

Ranking the correlations

These are the test scores in order of most correlated to least correlated to performance on unseen translations:

| Multiple R | |

| Unseen Previous vs. Next year | 0.724301 |

| E2L same year | 0.652156 |

| Oral previous year | 0.611353 |

| Vocab same year | 0.497062 |

| E2L previous year | 0.4901 |

| Vocab previous year | 0.439875 |

| GA same year | 0.403941 |

| Oral same year | 0.378783 |

| GA previous year | 0.364568 |

Grammar Analysis ranks very low in this list, suggesting that it is not drawing from the same skills or characteristics that make a student good at translating unseens.

The most highly correlated factor was how well students did on unseen translation in the previous year.

The second most highly correlated factor was how well students performed in English to Latin translation in the same year.

The third most highly correlated factor was how well students performed in an oral performance of Latin in the previous year – their pronunciation and ability to add dramatic expression to a passage of Latin.

Conclusions

Greater attention needs to be given to whether we are testing the right things, and whether the tasks we set are really helpful to improving our students’ ability to read Latin in context.

I don’t like how much pressure and stress English-To-Latin translation puts on students, and it is no longer a requirement in the new study design for year 11; however, it seems to have been measuring something that really correlated closely to student performance in unseens, at least within the same year. This something could have been the students’ internalisation of the language, or it could have been their ability to monitor grammar-rules, or it could even have been their diligence and motivation.

Oral performance and pronunciation could play a much larger role in improving unseen translation skills than Victorian Latin teachers have given credit. The oral assessment is no longer a requirement in the new study design for year 11, but most teachers I have spoken to had already treated it as a very minor task or not even a formal assessment. The benefits of good pronunciation, if my limited data is showing something, are most observed in the longer term as students become better at acquiring language features. If this is the case, then we should especially emphasise oral skills and pronunciation in the early years so that the process of internalising Latin and gaining reading skills is enhanced throughout the course of study.

Grammar Analysis has very little correlation with students’ ability to translate unseens, both in the same year and in future years. It is one of the least (if not the least) legitimate language test in terms of predicting ability in unseens.

Similarly, but not quite as bad, are traditional vocabulary tests (“provide one definition for the Latin word”). Even if these are very useful words taken from large, frequency-ordered lists, doing well in a vocab test is not a good predictor for how well students can recognise the words in real contexts.

One response to “Grammar Analysis scores don’t correlate with unseen translation ability”

[…] As a language teacher, I have found that my students’ scores in grammar tests have had little to no correlation to their scores in broader interpretive skills such as translation. This suggests that explicit […]