I started writing this essay, which grew to over 16,000 words, with the goal of explaining ‘how to learn Latin on a budget in 2023: the most cost-effective autodidact strategies’. But during its month-long writing process, the essay turned into ‘how not to be deceived by well-meaning but terrible language learning advice’. Since both your money and your time are valuable, if you don’t want to be working needlessly hard while learning Latin, this essay is for you. I also propose a strategy which legitimately costs $0.00, so stay tuned for that.

In my previous posts, I listed all the places you can learn introductory Latin online with teachers who speak the language, through both live classes and self-paced courses. The average cost of the live courses was about $1,500, while the average cost of a self-paced course (one with pre-recorded video lessons) was about $500. For many learners in the community, even the relatively cheaper options for learning Latin with a teacher may be out of their price range. That is why so many opt instead for teaching themselves Latin. By becoming autodidacts (self-teachers), they can save hundreds or potentially thousands of dollars.

But many Latin autodidacts are vulnerable to being deceived by well-intentioned language advice which tells them to work hard at meaningless things instead of focusing on truly communicative, meaningful, and beneficial activities. In this article, I will explain the difficulties facing autodidacts, debunk some language learning myths, define meaningful activites, outline five viable strategies for learning Latin, and even talk about how cults of celebrity propagate misinformation, and how to avoid being deceived by them.

The difficulties of an autodidact

As a high school Latin teacher in my sixth year of teaching, I have a professional responsibility to learn how people learn languages, and to let my practice be informed by genuine scholarship and not just heritage practices or hearsay.

But it has taken me years to really open up to the field of Second Language Acquisition scholarship and start to navigate what we have learned so far on this topic. I am not alone in this – I know there are many language teachers (in both modern and ancient languages) who have similarly struggled to connect their teaching practices with what our current research says. It is much easier to simply repeat practices we have inherited from other teachers or language learners than to question the effectiveness of established practices like vocabulary tests, grammar quizzes, reading aloud round-robin style, reading aloud a role-play scenario, and so on.

This is a big problem for the public knowledge of language learning. School is often the only place where people have experienced any form of language learning. But the way that languages are taught in schools (even modern languages) is often more a product of tradition than reason. These traditions have been passed down and refined to suit the school environment – a place of constant tests and quizzes, school reports, parental expectations, grades, exams, and classroom behavioural problems.

Unfortunately, the classroom experience of language learning distorts public ideas of what learning a language ought to look like. This is unhelpful to an autodidact for two reasons. Firstly, they are no longer in a classroom. Secondly, the practices are not always the most effective for language acquisition: often even the language teachers who are the most on board with SLA research are forced to compromise between best practices for actually learning a language, and implementing a mixture of inherited practices that were fine-tuned for behaviour control and maximising test scores.

It is therefore no wonder that the public flocks to apps like Duolingo. They have grown to expect that language learning is an inherently unpleasant experience, filled with rote-learning, vocab tests, practicing verb conjugations, and translating isolated sentences into and out of the target language, or repeating boring stock answers to stock questions. If those unpleasant parts can be gamified to give you points and stars in an app (thus replacing the grade incentives that got you through school), then this app must have finally cracked the code for how to learn languages as adults.

This is, of couse, missing the point of what a language is. Learning a language is not just another version of learning your times tables in exchange for sweets, or learning a puzzle-solving algorithm to decode sentences from another language into your native language. Putting points and scores on an app doesn’t change the fundamental nature of what that app provides. The question we should be asking is not whether a gamified language learning app succeeds at being ‘addictive’, but whether it provides meaningful activity in the language, and how much, compared to other ways we could use our time.

I will not review Latin Duolingo here. But instead I want to encourage you all to look deeper into what it means to learn a language, and to investigate what is really important, and what is not. If you can understand the principles of language learning, and what a language fundamentally is, you will be able to develop sustainable, satisfying language learning practices which are adapted for your situation.

I encourage you not to label yourself as ‘conservative’ or ‘progressive’ before deep-diving into how we learn languages. We are talking about a biological mechanism in our brains, how it works, and how we can give it the right conditions for language learning. This question is not a political or theological one, but a question of how our bodies and minds truly work, facts which affect people of all outlooks.

Language learning principles

This is my very short summary of the fundamental principles behind language learning.

- Every human (unless they possess a language-related disability) has the necessary hardware to learn a language. You do not need to be exceptionally intelligent nor exceptionally diligent to learn a language. This is most obviously proven when you visit multilingual regions of the world. For example, my mother grew up in Malaysia, where she picked up five languages: English, Bahasa Malaysian, Mandarin, Cantonese, and Hokkien, only some of which were regularly spoken in her household. To her it was nothing special to know these languages, because everyone in the community knew several languages. Multilingualism is the norm for most regions of the world outside of rich Western Anglophone countries. Therefore the ability to learn multiple languages cannot be limited to individuals with genetically rare traits in the population, for it is not just the exceptionally intelligent nor the exceptionally diligent who successfully learn languages in multilingual countries.

- We have always learned through input. We learn languages by understanding meaningful messages in the target language. ‘Input’ is anything we interpret for meaning: it is what we read or listen to. It is also important that the input is understood by the learner. Exactly how much needs to be comprehensible for input to count towards learning is debatable: some say that gist-level comprehension is enough to make meaningful progress from input, others say that optimal results happen at much higher levels of comprehensibility, where the learner knows 95% of the words in a text. Personally, I have experienced language growth at both levels – I’ve learned valuable skills from input that I understood at the gist-level, input that contained 95% known words, and input far below my level (which trains fluency with the existing knowledge). The Comprehensible Input Hypothesis (now known more simply as the Input Hypothesis) was built upon the findings that the brain has an innate mechanism for learning language in natural circumstances which can be effectively harnessed in second language acquisition. This internal language mechanism operates somehow separately from your conscious mind – a disconnect that we can directly confirm with experience. As a language teacher, I have found that my students’ scores in grammar tests have had little to no correlation to their scores in broader interpretive skills such as translation. This suggests that explicit knowledge of parts of the language is a separate beast from the actual ability to use and understand the language.

- Input is a condition for learning, not a method. It may sound like I’m mincing words here, but this distinction is important. No textbook has an exclusive claim on being ‘The Comprehensible Input Method’. It is often mistakenly believed that Hans Ørberg’s Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata: Familia Romana is ‘The Comprehensible Input Method’. In fact, Familia Romana was first published in 1957 under a different title, before the Input Hypothesis was proposed – it literally could not have even been informed by the research around input. It was also not substantially revised to align with the Input Hypothesis; the revisions to the text in 1983 and 1991 are minor in nature and do not change its fundamental methodology. Counter to Nancy Llwellyn’s speech In or Out of Ørberg, Ørberg did not continuously refine it over 50 years of his lifetime, any more than any textbook which gets republished every so often with new editions deserves the title ‘continuously refined’. If you don’t believe me, just compare a 1957 copy of Lingua Latina Secundum Naturae Rationem Explicata to today’s Familia Romana and try to find any meaningful differences in the method. But despite not being written with the Input Hypothesis and modern SLA research in mind, Familia Romana provides a lot of material which can be used as input. So do many other sources which will be discussed below, both older and younger. Any textbook containing substantial Latin text can be used as a source for input (whether the book is written completely in Latin or not!). And, in fact, even textbooks in the grammar-translation genre such as Wheelock’s Latin provide a non-zero amount of input in the form of the sentences used as exercises for translation (although all grammar-translation books contain much less input than the graded reader style textbooks). Input can even be directly taken from authentic texts under certain circumstances, if they can be made sufficiently comprehensible to the learner (as we will see in the old interlinear method below). In sum, you do not have to adopt any particular textbook as a necessary consequence of accepting the Input Hypothesis, but it will be wise to pick resources and strategies which supply more input over those that supply less.

- Everything works… eventually. Since every method involves a non-zero amount of input, every method will eventually work with enough time spent on it. Some methods are just more time-efficient than others. And some methods are more intrinsically enjoyable than others, leading to a higher likelihood that learners will persist with the method. When evaluating a language learning method, it is not meaningful to defend it on the basis of ‘it worked for me’ or ‘it worked for so-and-so’. Everything works if you try it for long enough. It doesn’t need to be good to work, and many highly inefficient strategies propagate because the few people for whom it worked are the most vocal in telling everyone that it worked for them.

- Nothing hurts. There is no language learning technique that will cause permanent damage to your language abilities. Yes, even ‘translating in your head’ will not cause permanent damage. You do not need to force yourself to stop doing that; it will go away by itself. (I know this because I did all the ‘wrong’ things when I learned Latin – I translated everything, either on paper or in my head. Despite this, the inner translator voice eventually went away as I read more.) We also do not need to fear language fossilisation: making mistakes early and not being immediately corrected on them will not damage your language journey in the long run. At most, you may develop a temporary misunderstanding in the language that will later be corrected from the overwhelming mass of input. You also don’t have to master every lesson in the order pre-determined by any textbook – it’s okay if an apparently ‘basic’ concept eludes you for a long time. Many of the grammar items considered ‘basic’ to a language are in fact late-acquired features, because the order in which we have traditionally taught grammar does not correspond to the natural order in which grammar is actually acquired (and yet, people still learn within these imperfect systems!). Children do not need to master every feature in a perfectly orderly manner to make progress in language acquisition, and neither do you. The things that actually do stop people from reaching mastery in the language are loss of intrinsic motivation and lack of appropriate resources, which causes people to stall out and quit.

- You don’t have to be young to acquire a language naturally. People often feel nervous about learning a language as an adult or even as a teenager because they think they’ve missed a critical window of time in which natural language acquisition is even possible. Granted, there are some reasons this idea exists: the first language acquisition process will not look the same as a second language acquisition process, because the presence of another language in your brain changes how you approach the second one (in both helpful and annoying ways). In addition, the activities which children are likely to do (playing in the park with other kids, using very basic language in a low-stress environment) are different from the language-learning situations that adults find themselves in. But while adults will generally participate in different language activities compared to children, the underlying mechanism for acquiring a language remains more or less the same. There is no cut-off age for acquiring a language naturally as an adult through input. As an extreme counter example, Steve Kaufmann, who knows 20 languages, learned more of them after turning 60 than in his youth. In 2022, when I was 30, I was self-learning Italian from scratch (mainly through watching TV shows) and found that natural acquisition worked well, even though I’m not in my 20s any more. You don’t have to be a child to learn from input.

- Language acquisition is slow. Think about how long it takes for a baby to acquire their first language: they get constant input from loving parents who only speak in the target language(s), every day and every night. Even with that amount of language learning time, it takes them about 2 years before they can start stringing together very short sentences, often unintelligible. As adult learners we have an advantage over infants in that we already have a fully functional first language (and a longer attention span), but even for us it takes a long time to see the fruits of language acquisition. It is possible to go from complete beginner to low-intermediate in about one year of dedicated, consistent study, say an hour every day. It’s not really possible to go from complete beginner to high-intermediate or advanced in just a year. There is no method which will speed up an inherently slow process like language acquisition, except dedicating more time per day to meaningful activities in the target language.

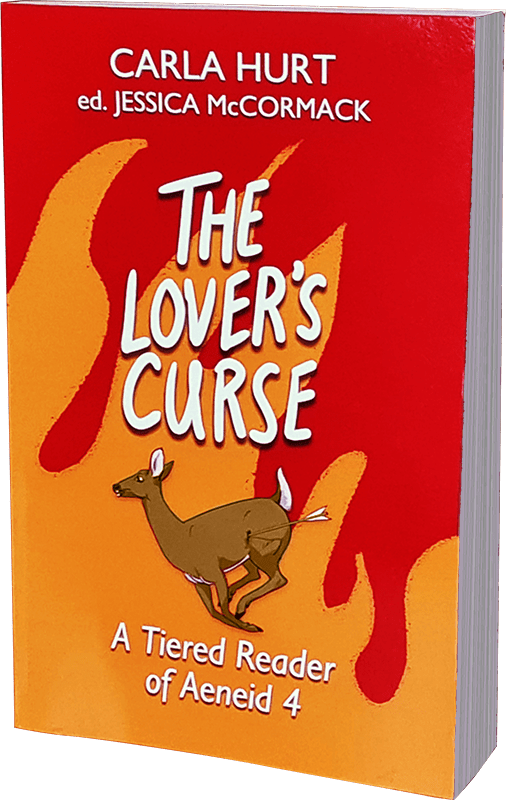

- It takes less time to reach the intermediate plateau than to leave the intermediate plateau. Language learning speed is not linear: it starts off relatively fast, then slows down dramatically at the end of the beginner stage, and stays at that slower pace throughout the intermediate and advanced stages. While beginners can make relatively faster and more noticeable improvements in their language abilities, intermediate learners struggle to see their progress, and take a longer time to reach advanced levels than they had taken to reach intermediate levels. Consequently, if everything goes well, you’ll be spending a lot less time in the beginner zone than you will in the intermediate zone. Given this perspective, it doesn’t matter all that much how you reach the intermediate plateau. All beginner pathways will converge there eventually, and then you will all be in the same boat, facing the same general difficulties in navigating intermediate content. So, you don’t have to stress so much if you took a less-than-optimal path through the beginner material: regardless of how you reach the intermediate plateau, you will have to change tactics to accommodate its new challenges. Although intermediate learning is outside the scope of this article, I’ll briefly state here that you will most likely be reading extensively through intermediate-level material, incorporating gradually more advanced texts with the help of tiered texts, interlinears, and/or pharr-style commentaries as needed. I am working on an upcoming book for intermediate learners, a 30,000 word intermediate reader called The Lover’s Curse: a Tiered Reader of Aeneid 4. Reading authentic texts with the help of easier Latin versions that render Vergil’s poetry comprehensible is a great way to extend your skills as an intermediate learner, and I’ll be distributing free digital copies of it upon release to anyone who signs up to my Latin email newsletter. But for beginner learners, this is our main takeaway: What you do to get yourself from beginner to intermediate has less and less effect on your final language level the longer you keep learning at the intermediate and advanced levels.

Now that we have some idea of what language learning constitutes, I want to focus on the most important thing you should do when learning a language.

Meaningful activity in the language

If there is only one thing you do every day in your language study, it should be meaningful activity.

Language is a system of words and grammatical forms (taken together as ‘forms’) which are used to express meaning: a human thought, a command, an outcry of delight, a lament, an evaluation, a story.

Interpreting and expressing meaning is fundamental to the nature of language and how we most effectively learn it. Our brains have been learning language through understanding input for (presumably) as long as we have had languages. People who grow up in multilingual parts of the world effectively learn multiple languages without considering it anything special, because they use the languages as languages: systems of communicating meaning.

If we want to take full advantage of the very part of the brain which is best suited to learning languages, we should be focusing most of our time on doing meaningful activity in the language: activities which require us to either interpret or express meaning, or both. This is the core of the communicative approach.

We can prove that meaningless activities are not necessary for language acqusition, because human beings of all cultures instinctively recoil from meaningless activity, while only in some language learning cultures do people actually bother with meaningless activity. I know that my mother growing up in Malaysia did not do any flashcards, deliberate grammar study, or fill-in-the-blank exercises, because when I asked her how she learned her five languages, she said she couldn’t remember how she did it. If she had worked away at any meaningless activity to acquire any of the languages that weren’t normally spoken in her home, she would have remembered it.

By contrast, meaningful activity is essential to language learning, because making form-meaning connections is the basis of learning a language. Any activity which does not genuinely engage with meaning is missing a crucial element. In order to associate all the various words, phrases, grammar, and syntax with their meaning, we need to encounter them many times in contexts where their meaning matters.

Meaningful input

A ‘meaningful’ input activity is one in which meaning is so intrinsically bound to the activity itself that you cannot succeed at the activity without understanding the meaning expressed by a source text. For example, if your task is to ‘evaluate which retelling of a myth you find more entertaining’, you cannot successfully make a comparison of the two texts without understanding at least part of what is expressed in both texts.

An input activity can also be shown to be inherently ‘meaningful’ if there is a positive relationship between how much you understand the language involved and how much you succeed at the task. For example, you could succeed at creating a surface-level comparison of two texts if you only understood a little of each. But you can make a better comparison of the two texts the more you understand of them.

By contrast, meaningless activities are possible to complete without understanding meaning, and the success of the activity does not correlate positively with how much you understand. For example, you may be told to ‘read a story out loud in full before understanding it’. But it is very possible to read something aloud and understand literally nothing in it. The mere act of vocalising something does not guarantee that you have processed any of it; in fact, you may be processing less of it in that activity because you have to split your attention between carefully pronouncing words and trying to understand the actual story. Especially if you are reading in front of other people, you can completely mindblank on what you just said aloud, which requires you to do a second reading in your head to actually understand the text, revealing that the first reading was pointless. You may be training your pronunciation in that activity, or your recitation skills, or public speaking, but it doesn’t help you in progressing towards actually understanding language. The ‘success’ condition of the ‘read it aloud in one go’ activity is that you confidently vocalise a story from start to finish out loud without stopping or repeating yourself. Someone who does this with optimal pronunciation and no interruptions does not necessarily understand the story better than someone who mumbles, stops, butchers the pronunciation, and trails off while thinking about the story. Therefore, the activity of ‘reading aloud a new story in one go’ is not intrinsically tied to how well you process the meaning of the story: it is not a meaningful activity.

That doesn’t mean that the entire category of ‘reading aloud’ is meaningless. For example, ‘whisper-reading’, a practice where you murmur the words aloud to yourself while focusing chiefly on the meaning of what you’re reading, permitting yourself to stop and think and re-read sentences wherever necessary, and not worrying too much about how well you produce sounds, is essentially the same as ‘reading for meaning’ but with the additional support of letting yourself murmur the words, which some people may find helpful for their focus.

For every example that I list as a ‘meaningless activity’, you could probably come up with a similar practice which does involve meaningful processing of the language.

My intention in providing a list of examples and counter-examples is to train you to discern the difference between a meaningful activity and one which is mostly busywork or a distraction. You also don’t have to do all of the meaningful activities I suggest; these are just illustrations of the type of activity that compels you to interpret meaning.

Here are some examples of meaningful input activities:

- Read a Latin story and understand it. ✅

- Watch a Latin video and enjoy the substance of what it is saying.✅

- Listen to an audio recording of Latin while doing chores, and at least part of the time you catch what is being said and understand what it means. (The more you can catch, the better)✅

- Read a Latin story, sometimes using an English translation to help you understand what the Latin says, while gradually looking more at the Latin half than the English half as you progress with the goal of getting more engrossed in the Latin story.✅

- Reread a story you had previously read, and see how much of it you can remember and if your memory of the story is confirmed in this rereading.✅

- Read two versions of the same story or myth in Latin, and evaluate which version you prefer. ✅

- Listen to a podcast in which you can understand at least some of what is being said and can follow the gist of the conversation; occasionally you laugh when the speakers laugh because you actually get their jokes.✅

- Read (or listen to) questions about a story you read in Latin, understand the questions, and answer them either mentally, with a gesture (eg. a nod or head-shake), or aloud in English or Latin. ✅

- Read a flashcard showing a sentence from a story you have previously read, with a target word highlighted. Recall what the sentence means and remember where it came from in the story, and check to see if you understood the target word. ✅

- Reader’s theatre: take some time to consider how you could read aloud a character’s dialogue in a way that expresses their emotions in the scene. As you reread the text, think about which lines and which words should be emphasised, and why. Then perform the dialogue like a voice actor. You may choose to record your goofy voice to listen to it again later. ✅

The following activites are NOT ones which require you to meaningfully process input:

- Before understanding what it says, read aloud a text in one go, carefully thinking about your pronunciation. 😐

- Take turns in a group reading aloud a text round-robin style.😐

- Search a text for examples of words in the genitive case by looking for words which end in the letters -ae, -arum, -i, -orum, -is, or -um, and label them as ‘genitive’. 😐

- Solve an exercise like ‘Iūlius et Aemilia in vīll__ habit___ cum līber___ et serv____.’ by finding a matching sentence in the text and copying across the endings without processing the meaning. 😐

- Answer a Latin comprehension question, eg. ‘Num pāstor sōlus in campō est?’ by finding a language chunk in the story that matches it and copying it verbatim as an answer to the question without understanding the meaning of the question or answer. 😐

- Review a flashcard which has one word on the front, “is, ea, id” and say to yourself the English translation, “he, she, it; that”, and do this with 20 other flashcards taken from the top 1000 words without context. 😐

- Listen to a song in Latin for entertainment and sing along even though you have no idea what the Latin means. 😐/✅

I put both symbols next to the last activity because it doesn’t quite fit in either category: it is very possible to enjoy a song for its music while understanding literally none of the lyrics, so it fails the first criterion of a meaningful input activity by allowing zero comprehension to be a successful state. However, the more you understand of the lyrics, the more you can appreciate the way the song is crafted as a unified piece of art involving both music and language. As long as the song expresses meaningful thought with its words, it is inherently motivating the listener to search for the meaning of its messages. Nevertheless, songs, like poetry, tend to use rare and peculiar words for effect, which usually makes them rather unsuitable as beginner material. This doesn’t mean we should avoid listening to songs, just that we need to temper our expectations about what they can do for our language growth, at least in the beginner zone.

Songs aside, most of the activities I have listed as meaningless busy-work tend to be quite mechanical and dull, whereas the activities I listed as meaningful input activities find their sucess in the simple pleasure of understanding meaning in the language, and are tied to a meaningful context. This is a win-win for us language learners. It turns out that the most valuable activities you can do in a language are also the ones which are the most inherently enjoyable.

And I don’t mean ‘enjoyable’ in the same way that winning a lottery is enjoyable. Reading a language book in bed is not going to suddenly spike your dopamine like consuming a can of fizzy sugar-water. But it gives you a similar level of wholesome pleasure as taking a walk in the sunshine, or chatting with friends. Understanding meaning in another language is a simple pleasure that we can nurture and cultivate, turning it into a habit we actually want to do.

(Keep this in mind when we later discuss the pitfalls of language learning methods which require the learner to repeatedly complete frustrating tasks as if they were unavoidable facts of life.)

Now since it is 2023, someone is going to ask whether AI tools such as ChatGPT can be a good source of input. My short answer is that the Latin produced by ChatGPT in 2023 is riddled with errors of grammar and idiom in almost every sentence, making it unsuitable for autodidacts. In the future these tools will probably become more accurate, at which point we could start talking about whether humans fundamentally prefer listening to humans, robots, or a combination of the two. In the hands of an advanced Latinist, ChatGPT does an adequate job of generating rough drafts for stories which can be edited for both accuracy and better storytelling. This is how I’ve used it in my classes so far: I make it draft stories which I fix up for my students. But without that human intervention, it is just not a source that a beginner Latinist can trust in 2023.

Now that we have discussed meaningful input, let us turn to meaningful output.

Meaningful output

For some reason, even more than with input-based tasks, our Latin community is prone to recommend output activities which do not actually require meaningful communicative intent. It almost seems like output activities get a ‘free pass’ of approval: the mere fact that certain activities involve speaking or writing of any kind, even if it is purely a mechanical exercise with a pre-determined correct answer, attracts positive labels like ‘active Latin’, in contrast to the negative label of ‘passive Latin’ that is applied to input-based activities.

In reality, SLA researchers do not divide the world of language learning into ‘active’ meaning ‘good’ and ‘passive’ meaning ‘bad’. They do talk about the ‘receptive’ modes of listening and reading in contrast to the ‘productive’ modes of speaking and writing, but no one is trying to claim that receptive modes are truly passive, somehow involving no activity from the brain to process.

‘Communication’ doesn’t just mean ‘talking to each other’: it includes all forms of the interpretation and the expression of meaning. Reading is a communicative act. Listening is a communicative act. What makes an act communicative is the interpretation or expression of meaning, not whether words come out of your mouth or ink comes out of your pen.

But it must be asked, what value does the language learner gain from producing output? There is longstanding debate among SLA researchers about the role which output should play in language learning, and this is worth considering. Positions vary from those who believe output is unnecessary, and who claim input alone is sufficient for developing a functional proficiency in the target language, to those who believe that output is necessary for a fully-rounded and more deeply inter-connected understanding of the language.

On the side of those claiming that input is sufficient for language development, there are notable cases of people who developed a sophisticated comprehension of their target language through years of purely input-based activities. Matt vs Japan learned Japanese to a very high level largely through watching entertainment media, and reported that he only needed a couple weeks of practice to activate his wide knowledge to speak Japanese to other people.

But in my experience, moving from being a silent Latinist to a speaking Latinist, I’ve found that converting receptive knowledge of the language into productive skills requires a substantial amount of rewiring the connections between your thoughts and words. Recalling a word that you only know at sight is like tracing the connections backwards. ‘Activating’ your knowledge of the language is an ongoing process, not something which you can instantly carry over from your reading comprehension.

One thing is clear: if you do create output, you should expect the complexity of what you can produce to be lower than the complexity of what you can comprehend. It is through comprehending input that humans gradually build a mental representation of the language – a complex systematic image of what exists in Latin. Output is what we can produce by attaching active-recall connections to what we have already learned. Therefore, we cannot produce output unless we have ingested sufficient input. Because of this, you should not be expecting yourself to produce output at the same level of complexity as the input you are receiving, and input should precede output.

But not all Latinists even say that they want to produce output at all. If one is content to simply consume and not produce, is output a necessary and essential part of the language learning process? Merrill Swain’s Output Hypothesis, which makes several claims for why output is beneficial and even essential to the language learning process, was originally developed because she observed that second-language French immersion students had a very high level of comprehension in French from receiving ample input but lagged behind their native speaking peers in their ability to speak in French. I’m willing to bet that many Latinists would in fact be perfectly content to be those French immersion students Swain was dissatisfied with, who had high comprehension but little productive ability, because they are happy not to speak or write in Latin. Even if output can be shown to have some beneficial impact on comprehension, it seems that input alone is already capable of taking people to high levels of comprehension, the one skill that seems relevant in Latin. Why then should we bother producing output?

It is beyond the scope of this essay to fully articulate the reasons our community should or should not be encouraging productive Latin. But I heavily suspect that some of the fear and bitter resistence towards output in Latin may actually be a consequence of how forced, meaningless output practice in school language classes has left many people with a strong dislike of the practice, prompting them to seek out Latin precisely because it is a language that no one has to speak. If that is the case, then recommending cookie-cutter activities taken from forced-productive practices in language classes is the absolute worst way to promote ‘active Latin’ as it will instantly reinforce the natural and cultivated dislike of being made to talk empty words for the sake of ‘language practice’.

Fundamentally, human beings don’t have a natural dislike of speaking. We dislike being forced to speak without any good reason.

It would be much more beneficial if we thought of things the other way around: you don’t have to speak and write in Latin. You get to speak and write in Latin. All that lifetime knowledge of the language you’re carefully building up? Instead of dying with it and taking it all to the grave, you get to pass it to the next generation through the natural mechanisms of output and interaction, by talking and writing and collaborating with other people in Latin. The better your output proficiency gets, the more you can help other people enjoy the language that you enjoy – whether you are a teacher, creative writer, or just an average person who participates in a group chat once in a while.

Have you noticed how intrigued and inspired young people get when they see living people speak a dead language? In an age where old content gets buried under mountains of new content every single day, people who produce Latin are making our language seen and heard, especially by the younger generations.

But productive ability doesn’t appear overnight. Like language acqusition itself, learning to be a good speaker or writer in the language is a long process. Most of what you write or say from the beginning will be full of errors, including both obvious grammatical errors and more subtle problems with the idiom. It is important not to fixate on errors initially, but instead to learn how to use the resources you have available to make yourself understood by other people, and build competency from there.

Meaningful output activities, where the focus is on communicating information to a sympathetic listener, rather than on avoiding errors, are the most effective ways to build this resourcefulness. For an output activity to be meaningful, you need to be able to answer two questions (taken from Henshaw & Hawkins’ language pedagogy book, Common Ground):

- What information or content is being conveyed?

- What will the audience do with the information?

Communciative output activities require an audience that cares more about what you are saying than how well you are saying it. You can find sympathetic Latin speakers on the Latin subreddit, on the various Latin Discord servers (such as the general Latin Discord, and the Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata Discord), on the weekly Latin Zoom chats, and by writing a post in the Latin subreddit asking if there are any Latin speakers in your city or local area. Try contacting the nearest University that teaches Latin to ask if there is a local Latin club. You can even directly hire Latin speaking tutors on iTalki.

Here are some examples of meaningful output activities:

- In Latin, command other people to do the actions you tell them to do (eg. ‘venī hūc et dā mihi calamum! grātiās tibi!‘), then swap roles. To prepare for the activity, you may create a print-out with pictures captioned with example commands in Latin, to serve as a visual reminder for yourself and others. ✅

- Write new Latin comprehension questions about a story you have read which you will share with friends as an activity to check their reading comprehension. ✅

- Respond to Latin comprehension questions in Latin by writing answers, then indicate which question was the most and least interesting to answer. Compare your opinions with other learners and colloborate to write better questions to replace the ones which were considered the least interesting. ✅

- Write alternative ways to rephrase parts of a story from your textbook, so that you can later read that story to other people in a Latin study group and explain it aloud in Latin using these variations in phrasing for clarification. ✅

- Write a variation of a Latin story you have read in the textbook, but replace the main characters with you and your friends (or characters from memes) and change some of the events or the outcome of the story. Then share it with your friends to see if they enjoy it. ✅

- Collaborate with another Latinist to create illustrated children’s stories: each person writes a story from your home culture, and the other person draws illustrations. Team up with an advanced Latinist to check your idiom and then share the stories on the Latin subreddit with their pictures. ✅

- Prepare dot points in Latin about how you would introduce yourself to new people, then at a Latin speaking group (such as at a weekly Zoom meeting), introduce yourself to the group using the script you prepared while also venturing off-script to say more or clarify things if people don’t seem to understand.✅

- Join a Latin speaking group and contribute meaningfully to the conversation (even if you just start by saying short phrases like ‘euge!’, ‘prō dolor!’ or ‘mihi placet …’ while others do more of the talking)✅

- In a Latin Discord server chat, read what other people are writing and then ask other people in Latin to tell you more details about what they are talking about if it’s a topic that interests you. ✅

- In a Latin Discord server chat, when people ask you to explain or clarify what you mean, find a way to make your meaning clearer by giving examples or using different phrases. ✅

- In text chat or voice chat, ask a Latin speaker about their family or what they do every day. Discuss how your families or daily routines are similar or different. ✅

Each of these suggested output activities may be suited for different levels. Activities which involve making lists, short utterances, or minor alterations to existing content are the most accessible to beginners, while activities which involve intricate description or sustained logical argument are more suited to speakers at higher levels.

Some output tasks can be done away from a human community. An audience can include yourself, if you find writing to yourself therapeutic, or God, if you are religious. Reflection, gratitude, and prayer can be meaningful practices in which the main goal is to use language to express the content rather than to avoid making errors.

- If you are the kind of person who normally keeps a diary, try journalling in Latin to see what thoughts come to the surface. Do you think or feel differently in Latin than you do in your native language? ✅

- Gratitude journal: In Latin, make a dot point list of things which you appreciate in life. Then write a prayer or a gratitude journal entry summing up this list and expressing thanks for these blessings. ✅

- Scripture reflection & prayer: Read a passage from holy scripture. Outline in short dot points what the passage might have meant for its original audience. Reflect on what wisdom it may bring to our current context. Write or say a prayer asking for God’s help in applying the wisdom of this passage to our everyday lives. ✅

The following activites are NOT examples of meaningful output:

- Take a sentence from the text and turn every singular plural, every plural singular. 😐

- Take a story and rewrite it in a different tense, keeping everything else the same. 😐

- Take a sentence from the text and retell it using an accusative and infinitive indirect statement. 😐

- Read aloud the script of a role-play, taking turns in a group to pronounce aloud your assigned lines, while not getting other people to meaningfully act upon the information you are saying aloud.

- Copy out a Latin story from the textbook in your own handwriting. 😐

- Transcribe a text from an audio recording. 😐

- Translate isolated random English sentences (e.g. those sourced from a prose composition book) into Latin. 😐

- Take an English translation of a Latin text and translate it back into Latin, checking to see where your version and the authentic text differs.😐

- Commit a text to memory and recite it aloud from memory. 😐

- Mimic an audio recording by repeating aloud what it says. 😐

These activities lack a meaningful communicative purpose: you are not conveying information to an audience who will listen and act upon what you say to them. They are practice-for-practice’s-sake, and not a true substitute for the real thing that practice is supposed to be bringing you towards.

Some people will defend these practice activities by saying that a ‘beginner has to start somewhere’; it is ‘unrealistic’ to expect beginners to produce meaning in the language; there is some unspecified amount of time beginners need to ‘practice’ before doing something real. They may say that most people don’t have anyone to talk to in Latin anyway, so this is how they can train themselves to be ready for meeting someone to talk to, some distant day in the future.

This is wrong on several counts.

Firstly, we have already shown several examples of meaningful output activites that learners can start to take part in even before they gain command of creating original full sentences. Activities involving creating lists, making short utterances, or recycling material from texts or other speakers’ words are accessible output activities for novice level speakers.

Secondly, I have already explained several practical ways to find Latin speakers both online and in person. Meeting someone you can speak Latin with is easier today than it has been for a very, very long time. (This is coming from someone who lives in Australia, which is about as geographically far from the European and American conventicula as you can get.)

Thirdly, mandating that beginners pre-train their accuracy before they start meaningfully communicating sends the damaging message that you ought to be very sure of what you say before you dare open your mouth to speak. In reality, if you must wait until your output is reliably accurate and beautiful before you start speaking, you will never be ready to speak, because it takes lots of experience communicating in realistic situations before you can begin to produce high quality output in realistic situations. Rather than focusing initially on accuracy, beginners should focus on being intelligible with the resources they have, and then work to improve their proficiency from that baseline.

As Henshaw and Hawkins write in Common Ground, ‘Novice and intermediate learners require a sympathetic interlocutor, rather an a red pen.’ Back-translation, grammar manipulation exercises, and Latin prose composition provide the ‘red pen’ of corrective feedback but not the ‘sympathetic interlocutor’ who listens and responds. While such communicatively pointless exercises may practice active recall and highlight gaps in ability, they do so at the cost of being intrinsically demotivating and inhibiting for most human beings, who seek to be heard and seen for their meaningful contribution rather than ignored for content and scrutinised for errors. It is no surprise then that the casually successful multilinguals of the world who pick up local languages like Hokkien and Cantonese don’t bother with the equivalents of prose composition exercises, but just get down to meaningful communication with real people.

These empty activities also perpetuate unrealistic expectations of what output should look like during the learning process. Ordinary people under natural circumstances do not produce output as beautifully perfect as the chapter they are up to in Familia Romana, but artificial production activities keyed to each chapter clearly assume that they should.

For a more realistic view of the productive capabilities of learners, we can read modern language standards such as the ACTFL proficiency guidelines for novice, intermediate, and advanced learners. Novices are clearly described as not yet having full command of the sentence: they ‘communicate short messages… primarily through the use of isolated words and phrases’. They are often unintelligible: ‘Novice-level speakers may be difficult to understand even by the most sympathetic interlocutors accustomed to non-native speech.’ The goal of a novice-level speaker is not to immediately start producing perfect output, but to move step by step towards the next rung of the ladder: intermediate-level proficiency, which features full sentences that are more intelligible to other speakers. Intermediate-level proficiency is itself not error-free, as ‘patterns of error appear’ even as late as Advanced High.

The bottom line is that becoming competent at producing output is a process that takes time, so if we need to do a lot of it, we would be better off enjoying it. Would you rather embark on an indefinite amount of meaningless practice devoid of a communicative context that may or may not help your productive skills in realistic situations, or would you rather cultivate meaningful communication with real people? Intrinsic motivation and enjoyment are just as crucial in the output activities as they are in the input activities, because in the long term we are more likely to sustain the habits that we enjoy.

Choosing a core strategy

So far we have discussed examples of meaningful activity in the language. But how would you go from start to finish if you are teaching yourself the equivalent of an introductory course in Latin? What is the step-by-step path for a newcomer? In this section we will discuss five main archetypes representing the most successful strategies for learning Latin using the resources currently available in 2023.

I chose to present five archetypes here rather than one ideal strategy because it was not possible for a single strategy to optimise all factors that Latin autodidacts find valuable. A strategy which is simple to execute makes a necessary trade-off against a strategy which provides greater variety of input. I also found that in the current market, the resources which were the lowest cost were not the most delightful. There are also strategies which may be sub-optimal on some counts but increase the user’s confidence that the method will work, making them more likely to persist with the method.

You can mix and match elements from different archetypes, or swap strategies partway through. You can also add any meaningful input or output activity on top of the core strategies here.

1. Barebones Ørberg

This strategy is well known in the Latin subreddit, r/Latin. It has been used by a very large number of autodidacts over the years, increasing a newcomer’s confidence in the method. While not without flaws, it optimises simplicity and cost-effectiveness and can be a good place to start if you are worried about being overwhelmed with too many choices.

The method is as follows:

- Read through a chapter of Hans Ørberg’s Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata: Familia Romana, mainly focusing on understanding the Latin and not forcing yourself to mentally translate it into your native language.

- (Optional but recommended: listen to audio recordings of the textbook chapters as you go along, such as those on YouTube, the Legentibus app, or the official audio recording.)

- At the end of the chapter, check your understanding by completing the pēnsa (the exercises that are printed at the end of each chapter of Familia Romana).

- If the exercises reveal gaps in your understanding, reread the current chapter (or multiple earlier chapters leading up to the current chapter) and retest yourself until you are able to complete the pēnsa with 100% success.

- Repeat for every chapter of Familia Romana.

The strengths of this method are its simplicity and cost-effectiveness. It only requires you to obtain one textbook, Familia Romana, which will be used for the entire duration of the beginner phase. As a side benefit, because a large number of autodidacts are already using this method or something very similar (i.e. Deluxe Ørberg) it will be easy to find study-groups on the Latin subreddit and the LLPSI Discord server who can learn alongside you.

The drawbacks have to do with its use of the pēnsa as barriers to progression. Even if the pēnsa involved genuine communicative output (they do not – there is no real audience for any of the pēnsa and two out of the three types of exercises are mechanical fill-in-the-blanks), it is not output that drives acquisition but input. Output can serve as a way to highlight gaps in understanding and offer opportunities to test hypotheses, but it does not in itself remedy those gaps in understanding. The learner has to return to processing input to fill the gaps. The pēnsa mainly force people to do more re-reading of previous content than they otherwise would have been inclined to endure, which increases the amount of exposure to target features, but at the cost of also increasing frustration.

The total reliance on one textbook to provide all input in a very tidily-packaged sequence of grammar is also a flaw of the method. Humans do not naturally acquire grammar in the order that it is taught in a curriculum; there is an internal sequence of grammar which defies an idealised progression of noun cases and verb tenses. We also do not process everything we read, nor acquire everything we process: Henshaw and Hawkins write in Common Ground, ‘Neither teachers nor students have total control over what will and will not be acquired. Indeed, not everything from the input becomes part of the linguistic system, at least not in an immediate and predictable manner.’ Striving to acquire 100% of the material in every chapter is, in a very real sense, working against our human nature.

Despite these flaws, the ‘Barebones Ørberg’ approach is widely used in the Latin community, and offers a good starting point for anyone who wants to get into the process right away, without much upfront cost. The textbook retails for about $60, which might sound like a lot for a book, but for a Latin course it is extremely reasonable. Considering that you could be dropping about $1,500 to learn Latin with group classes or about $500 for a guided self-paced course of video lessons, a $60 textbook that you will be using for a whole year is not nearly as great an expense.

2. Deluxe Ørberg

Over the years, the Reddit Latin community has been growing more aware of the drawbacks of using Familia Romana as the sole source of input for the entire beginner stage. However, the community maintains a large amount of confidence and trust in the textbook as a kind of common-ground, touchstone resource for ‘learning all the grammar’ and ‘covering all the bases’. Therefore the subreddit has come to encourage supplementing Familia Romana with other LLPSI-branded resources keyed to its chapters. As a bonus, some of the supplemental stories are more delightful than the exposition-heavy texts in Familia Romana.

The shopping list is as follows:

- Familia Romana

- Colloquia Personarum

- Fabulae Syrae

- Download the free pdf of Fabellae Latinae.

- Exercitia Latina I

This method, paraphrased and summarised from the one currently recommended on the Latin subreddit, goes as follows:

- Read through each chapter of Familia Romana and the corresponding chapter of Colloquia Personarum (for Ch1-24) or Fabulae Syrae (for Ch26-34). Also read the corresponding story in Fabellae Latinae. Aim to read all of these at least twice.

- Listen to audio recordings of the above as some of the ways you consume this input.

- Complete the pēnsa for every chapter and the exercitia from Exercitia Latina I

- If you notice gaps in understanding through the pēnsa and exercitia, reread the corresponding chapters until you can complete the pēnsa and exercitia very quickly and accurately.

- Repeat for every chapter of Familia Romana.

As you can see, it is basically ‘Barebones Ørberg‘ but with more reading material. It retains the same drawbacks relating to the use of the pēnsa as barriers to progression and the burden of having to 100% master every chapter of content in the order it is presented.

I would even add that the extra emphasis on completing grammar-focused fill-in-the-blank exercises in the Exercitia is perhaps a move in the wrong direction, away from natural language acquisition through input and more towards forced output. The Exercitia are not going to harm anyone or prevent learning; they would train active recall, at the cost of not being a meaningfully communicative activity and thus providing more of a red pen than a sympathetic interlocutor. It is just strange to see continual, mandatory emphasis on non-communicative production tasks in a community that says it values a ‘natural’ and ‘input’ based approach to language learning.

While ‘Deluxe Ørberg’ is not as simple as ‘Barebones Ørberg‘, nor as cheap, it manages to increase the amount and variety of meaningful input per chapter and thus can provide a more delightful reading experience than getting stuck rereading only the same story ten times. The backing of the Reddit community increases the learner’s confidence in the method. It does however share the same flaws as ‘Barebones Ørberg‘ in that it expects that learners to be able to control what they acquire from the input, and falsely assumes that enough rereading and recall practice will always guarantee 100% acquisition of target features in any given chapter.

But because so very many autodidacts use Ørberg’s texts, there are ongoing projects to write additional stories and content that pad out every chapter of Familia Romana even further than the officially published materials, catering to a wider variety of interests. If you’re a Pokemon fan, you might enjoy Mike Saridakis’ Lingua Latina Per Pokemon Illustrata. Seumas MacDonald is writing a sci-fi novella keyed to each chapter of Familia Romana, titled Cassandra (it is currently only available to patrons on his Patreon). There are also additional Familia Romana resources on Anthony Gibbins’ website Legonium. Doubtless more projects keyed to Familia Romana will appear in the future due to the widespread use of the textbook.

3. The More the Merrier

These next two archetypes, ‘The More the Merrier’ and ‘The Public Domain Penny Pincher’, are inspired in a large part by Justin Armstrong (who is documenting his process of learning Latin through mass input on his YouTube channel), and also from my observations of Latin autodidacts who are comfortable incorporating reading material from textbooks other than Familia Romana as part of their overall diet of input. ‘The More the Merrier’ is essentially how I have been increasing my Ancient Greek proficiency after failing to achieve much fluency initially through grammar-translation, and incidentally is the same method that Seumas MacDonald describes in his recent post about 2023 Ancient Greek autodidact strategies. I am confident this strategy works even better in Latin, as there have been so many high quality reader-style Latin textbooks published in recent years.

The method is as follows:

- Buy (or legally download) a Latin reader-based textbook – it could be Familia Romana (probably the top pick for a first Latin textbook), or any other textbook which provides large amounts of input in the form of stories of graded difficulty such as Via Latina, the Cambridge Latin Course, Suburani, etc.

- Read through the stories with the goal of understanding and enjoying them.

- Incorporate rereading in your routine to get more value out of the stories. Aim to read each story at least twice. You could do the 2 reads one after another, or space it out and return to a previous story after reading other things.

- Do not get caught up on mastering mechanical production exercises, pēnsa, exercitia, etc. but if you feel like doing them for a laugh, knock yourself out. Tip: The exercises in the Via Latina textbook are a lot more interesting than most other Latin textbooks, and definitely worth trying out.

- If the book contains English essays on cultural topics, just skip them and focus on the Latin stories. You can briefly skim-read English grammar explanations, as it may increase your chances of noticing grammar features in the input, but don’t stress about it either way.

- When you find yourself getting stuck because the difficulty of the textbook has reached a point higher than your current reading level can handle, put this textbook aside, switch to another book series, and start again from the beginning.

- When you reach a point of getting stuck with difficulty in the new textbook, you can either start another new textbook or return to previous textbooks and continue reading them until the challenge becomes too difficult again.

- When you are able to read the final chapters of all your textbooks, you’re probably ready to start working your way up through intermediate reading material. Congrats! You’ve reached the intermediate plateau.

Here are some of my most recommended Latin reader-style textbooks:

- Ørberg’s Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata: Familia Romana. While I am certainly not the biggest fan of the storyline (I often find it desperately dull), it seems to have the easiest learning curve for the early chapters. It is probably the most user-friendly place to start.

- Aguilar & Tarrega’s Via Latina. A textbook does not need to be written entirely in Latin for it to provide useful input, but it is a nice feature nonetheless. Like Familia Romana, Via Latina is written entirely in Latin and uses marginal pictures to convey new words, providing lots of illustrations and in-language explanations. The exercises in Via Latina are the most varied, interesting, and meaningful I’ve seen of any Latin textbook to date. Overall the chapters are more dense with new material than Familia Romana, as this course was designed to ‘cover everything’ in a smaller volume of words, but nevertheless this textbook is a fun read and a worthy addition.

- The Cambridge Latin Course. This series has compelling narratives that move through a variety of genres such as ghost stories, romantic comedy, a mafia subplot in Egypt, and political intrigue. Although the glossy, colour-printed hard copies are quite expensive, currently in 2023 you can legally access all the chapter stories for free on the CSCP website in two places – if you access the stories through this link, you can click on every word to look it up in the dictioary. In the webBook version, you can leaf through the book and read the picture captions at the start of chapters which help give context to the stories. The series has been used in UK classrooms for decades, so you might be able to get used copies on the cheap, especially for older editions.

- Suburani. Characters and continuous plot are emphasised in this relatively new textbook. It features a large quantity of colour illustrations, including many pages of essentially comic-book panels continuing the main plot. How many Latin textbooks have this many richly illustrated comic-book panels? The physical books of Vol 1 and 2 are quite expensive ($55 each for a total of $110), but you can get a year’s digital access to both books for either $20 (for North Americans) or £15 (for people in the UK) with an individual online account.

- Legentibus. I would highly recommend checking out Daniel Pettersson’s short stories on his Legentibus app, as they are well-written and delightful. If you are not in the mood to purchase a year’s subscription due to the cost, it could be quite economical to buy just one month’s subscription for $9.99 and binge all of his beginner-level short stories at once.

I also recommend checking out Justin Armstrong’s ‘Optimised’ Latin Reading List, in which he suggests a reading order that roughly corresponds to a gradually increasing difficulty of comprehension, with links to each resource.

‘The More the Merrier’ maximises variety and delightfulness, as it provides the greatest flexibility for the user to choose textbooks and stories that appeal to them most. However, it is more expensive than other strategies (though still much less costly than taking classes or buying a self-paced video course). Having to buy a shiny new resource as the mood strikes adds some complexity to the process, as you may end up spending more time shopping and searching for resources than you otherwise would have preferred.

4. The Public Domain Penny Pincher

While ‘The More the Merrier‘ splurges on shiny new textbooks, ‘The Public Domain Penny Pincher’ thriftily uses as many freely available resources as possible in their quest to acquire Latin through mass input, absolutely maximising cost-effectiveness while also achieving some variety in reading material.

In reality, everyone can use freely available materials on the side of whatever they are currently doing. But for people who cannot afford even a single textbook, it is valuable for us to put together a strategy that can stand up on its own while literally costing $0.00 beyond your basic living costs and internet bills. Enter ‘The Public Domain Penny Pincher’.

The method would be mostly the same as the ‘The More the Merrier‘, except that we lack Familia Romana as an easy entry point for first textbook. I would have liked to recommend the Cambridge Latin Course online version as the go-to first text, because the ‘Explore the Story’ tool allows you to click on each word to instantly look up definitions, making it user-friendly for first-time readers of Latin. However, while this online textbook is still free in March 2023, I fear that it will probably be taken down in subsequent years and replaced with a subscription model, making it one day unsuitable for our Penny Pinching strategy.

No, in the spirit of the open source movement, a ‘Public Domain Penny Pincher’ strategy ought to start with a truly public domain work: something which is and always will be free.

My recommendation for first public domain textbook in this method would be one of these two: William Most’s Latin by the Natural Method, and Grey & Jenkins’ Latin for Today. These two textbooks seem to have attracted more love and attention than the other Direct Method Latin textbooks in the Public Domain, and I can personally attest that they are pretty enjoyable to read in terms of their subject matter.

Most’s Latin by the Natural Method focuses more on ecclesiastical Latin, and includes retellings of bible stories, which provides some familiar content. This is a plus if you are particularly interested in learning ecclesiastical Latin, but not a problem at all if your focus is on classical texts, as the ecclesiasical and classical dialects of Latin do not differ very significantly, especially not in the base language suitable for beginners. However, it is an annoyance that Most’s text does not mark macrons, which wastes the opportunity for learners to initially get used to the vowel quantities which characterise the natural rhythmic quality of the language.

Grey & Jenkins’ Latin for Today deals with classical subjects and contains macrons. Every story is paired with a detailed illustration, and very often the text focuses on describing and commenting on the contents of the picture. This aids in the comprehensiblity of the texts and grounds the language in a meaningful context. My only concern is that the stories feel rather brief, and there may not be very many repetitions of words before the next round of new words are introduced.

The method is as follows:

- Pick a first text (my top recommendations being either Most’s Latin by the Natural Method or Grey & Jenkins’ Latin for Today, if and when the Cambridge Latin Course online textbook stops being freely available) and read the stories with the intention of understanding the meaning and enjoying the story.

- Incorporate rereading in your routine to get more value out of the stories. Because public domain texts have a bit of a higher learning curve than contemporary paid textbooks, you might need to aim for higher numbers of repetitions, at least three or four, but the more the better. If you can vary the activity you do in subsequent rereads, you can make rereading less monotonous. For example, on the second reread, you could focus on visualising the scene as vividly as possible. On the third reread, you could consider miming actions to represent the words while you read. On the fourth reread, you could consider how a dramatic voice actor might interpret the lines, and reread it silently thinking about what emotion should suit each sentence, then try reading it out loud with exaggerated emotion. Record your silly voice and then play it back later as a listening activity. Vary the order in which you do these rereading activities according to your mood at the time, or drop the activities entirely if they don’t make rereading more interesting.

- Since we are dealing with sub-optimal readings, it might be worth getting some explicit knowledge of what is happening with the grammar, just to reduce confusion. Read the grammar explanations that appear alongside the stories to get an idea of what to pay attention to in the input, but don’t stress about having to memorise every fact or to master each concept in the chapter it appears.

- Any additional input you can get for free is going to make a significant difference to your growth in comprehension in this method. It would be beneficial to work your way through my curated YouTube playlists of beginner Latin content (which I have labelled Beginner A, Beginner B, Intermediate A, and Intermediate B) and even consider doing some interlinear practice with texts you find very compelling (see the interlinear method below).

- When you find yourself losing momentum or getting very frustrated at the difficulty level of the current readings, leave this textbook aside for now. Switch to another public domain book, and start again from the beginning.

- When you reach a point of getting stuck with the difficulty level in the new textbook, you can either start another new textbook or return to previous textbooks and continue reading them until the challenge becomes too difficult again.

- When you are able to read the later chapters of all your textbooks, you’re probably ready to start working your way up through intermediate reading material. Congrats! You’ve reached the intermediate plateau.

Here is my list of Public Domain or freely available texts that are most suitable for beginners:

- Most’s Latin by the Natural Method

- Grey & Jenkins’ Latin for Today

- Cambridge Latin Course online version (still accessible in 2023)

- Maxey’s Cornelia

- Maxey’s A New Latin Primer

- Fay’s Carolus et Maria

- D’Ooge’s Latin for Beginners

- Reed’s Julia

- Reed’s Camilla

- Godley’s The Fables of Orbilius

- The free beginner stories on the Legentibus app

- The free download of Fabellae Latinae

- The public domain novellas Sisyphus and Cloelia: Puella Romana

I would also strongly recommend combing your nearby libraries (especially university libraries) for copies of any more recently published reader based textbooks. Some have managed to obtain free (and completely legal) access to Ørberg’s Familia Romana this way.

The following public domain texts are useful rather later in the sequence, and many would be better placed as intermediate readers than as beginner readers:

- D’Ooge’s Colloquia Latina

- Appleton’s Pons Tironum

- Sonnenschein’s Ora Maritima (the second volume is Pro Patria)

- Vincent’s A First Latin Reader

- Spencer’s Scalae Primae

- Chambers & Robinson’s Septimus

- Nutting’s A First Latin Reader

- Nutting’s Ad Alpes (this is very prominently used as an intermediate reader)

- Appleton & Jones Puer Romanus

- Arnold’s Cothurnulus

- Bennett’s Easy Latin Stories

- Newman’s Easy Latin Plays

- Rylis’ Olim

- Winbolt’s Dialogues of Roman Life

Check out Justin Armstrong’s Latin Reading spreadsheet for notes about his learning experience in using many of these public domain textbooks.

‘The Public Domain Penny Pincher’ is the only autodidact strategy which literally costs nothing (while involving no illegal activity). The value gained per dollar spent is infinite!

However, the texts in this method are generally sourced from an era in which textbook authors did not prioritise writing stories to be compelling, but instead predictable. Other than the little pieces of recent freebie content like the free Legentibus stories and the CLC online stories, most of these works are not particularly delightful.

The method may also demand more effort from the learner to absorb the content of each story. The difficulty curve appears a bit steeper here than in ‘The More the Merrier‘, because of the more restricted range of texts. These texts (like most textbooks) were written with the assumption that a teacher would be guiding students through the material and supplying additional help or repetitions where needed, so reading them without a teacher makes them seem to breeze through content quite quickly. A Public Domain Penny Pincher may need to rely more on rereading and deliberate learning strategies such as ‘sentence flashcards’ to absorb the content than someone using more modern texts with built-in repetitions in longer stories.

The method is a bit more complex than simply opening up Familia Romana and going from there. It can be inconvenient to rely on reading pdfs and scanned books from archive.org, as you will be mostly reading from a computer screen. (And no, you can’t print them out – printing costs money!) There’s that feeling of having lots of tabs open in your browser, which makes me feel like there are lots of tabs open in my mind.

While Public Domain Penny Pinching may be more awkward than other methods, it is completely free and can be readily combined with any other strategy without adding any additional expense to that method.

5. Strange Bedfellows

What happens when you take a grammar-translation book such as Wheelock’s Latin, and study it alongside an input-rich graded reader like Familia Romana? The love-child of such a union is the strategy I will call ‘Strange Bedfellows’.

It is very difficult to get people to trust that they can safely let go of explicit grammar study. I can point to examples of how ordinary people growing up in multilingual parts of the world find their greatest success at learning languages through meaningful communication, how professional applied linguists learn very complex indigenous languages using input, how the traditional school system which emphasises explicit learning seems to have the worst success rate of any language teaching institution in terms of producing people who actually use those languages. But I cannot change the fact that most people who grew up in modern western schooling are deeply inculturated with the idea that explicit grammar study is essential to the language learning process.

On the other hand, it is much easier to convince people that input is beneficial. Most people will already have a very positive attitude towards extensive reading for increasing reading proficiency, and are willing to give it a try. Saying ‘no’ to grammar for them is a harder sell than saying ‘yes’ to input, so why not just say ‘yes’ to both?

I have seen many people use some form of ‘Strange Bedfellows’ to learn Latin; it is an extremely common strategy in the community. People who use it say that they are getting the ‘best of both worlds’, and ‘covering all their bases’, which gives them confidence. They would ask, ‘why do you have to pick a side?’ No matter who truly wins the debate over the sufficiency of input, the learner who incorporates ‘Strange Bedfellows’ has hedged their bets so as not to miss out on either of the potential benefits of input or grammar study.

The exact texts chosen can vary depending on the tastes of the learner. Here are some possible pairings:

- Wheelock’s Latin and Familia Romana. A classic pair for North American learners, as these two texts are available quite cheaply and are both widely used. If Wheelock’s is being used, however, I would also recommend purchasing the reader supplement keyed to each chapter of Wheelock’s, 38 Latin stories by Groton & May. Those 38 stories are not enough input by themselves to replace the need for at least one other graded reader textbook, but they are a nice addition to have alongside Wheelock’s chapters.

- Familia Romana and Latine Disco: Student’s Manual. The student manual Latine Disco is essentially an English explanation of all the grammar in each chapter of Familia Romana. It lacks those isolated grammar drills that help put the ‘explicit’ in ‘explicit learning’, but the advantage of choosing this pairing is that a large amount of reading can be keyed to each grammar topic explained in Latine Disco – not just the base chapters in Familia Romana, but also all the supplements discussed above in the strategy titled ‘Deluxe Ørberg‘.

- Most reader-style textbooks (other than the fully Latin Familia Romana and Via Latina) already have English grammar explanations paired with each chapter of content, and often come with corresponding grammar drills. Examples include The Cambridge Latin Course, The Oxford Latin Course, Suburani, Ecce Romani. You could simply purchase one textbook series and pair those readings with their corresponding grammar explanations.

- If you once learned (or failed) Latin in school through a grammar-book, and you have fond memories of that book, you could return to that nostalgic tome and pair it with any reader-based book from the list supplied in ‘The More the Merrier‘.

The method has two subvariants: grammar-first, and reading-first.

In the grammar-first method:

- Start reading a chapter from the grammar-based textbook. It will start introducing a new grammar topic with a chart and an explanation.

- Once you’ve understood the explanation, do the little drill exercises accompanying it to confirm that you’ve understood the isolated feature in single words, and if you want, read and understand the longer sentences too.

- Now switch to reading a story from your reading-based textbook, focusing first on reading for pleasure and understanding.

- Reread the story, and carefully notice when and where the target grammar feature occurs in the story to see how it is used in context. (If the story does not feature that topic right away, you can look forward to it appearing in a later story.)

- Repeat for the next grammar topic and chapter of each book until you finish both courses.

- If your reading proficiency is not as high as you want it to be at the end of the course, read several more beginner reader-based textbooks for pleasure until you reach intermediate proficiency.

In the reading-first method:

- Start reading a chapter from a readings-based textbook, focusing initially on reading for pleasure and understanding.

- Switch to reading a chapter from your grammar book. It will introduce a new grammar topic with a chart and an explanation.

- Once you’ve understood the explanation, do the little drill exercises accompanying it to confirm that you’ve understood the isolated feature in single words, and if you want, read and understand the longer sentences too.

- Now return to the story you read initially. Reread it, and notice if you can find any examples of the grammar topic occurring in the story. (If the story does not feature that topic, look forward to it appearing in a later story.)

- Repeat for the next chapter and grammar topic of each book until you finish both courses.

- If your reading proficiency is not as high as you want it to be at the end of the course, read several more beginner reader-based textbooks for pleasure until you reach intermediate proficiency.