-

Medulla project: website, summary and core values

I have launched a permanent home for the Medulla project on GitHub at this link: https://foundinantiquity.github.io/Medulla/

It is currently in the form of a static webpage (created from the GitHub repository’s ReadMe file) outlining the rationale and procedures of the project.

GitHub was chosen for hosting for a number of reasons. GitHub provides transparent public changelogs and version control. It also allows users to “fork” a project, meaning that other parties can duplicate it and take ownership of the new copy, modifying it as they see fit. These features are helpful for the long term maintenance and usefulness of any open source project.

Because the project is quite meta and abstract, it is important to define it succinctly and place constraints on what it is trying (or not trying) to achieve.

Project Summary

Here is my succinct definition of the Medulla project:

The Medulla Project is an open-source initiative to develop a shared planning document that outlines a core sequence of Latin vocabulary and grammar. This sequence enables chapter-by-chapter compatibility across different Latin textbooks, allowing educators to interchange materials more easily.

Core Values

In order to clarify the decision-making process, I also outlined a set of core values in this project.

- The Medulla project will be released under the Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, dedicating its content to the public domain and allowing unrestricted commercial and non-commercial use.

Creative Commons Zero (CC0) is the most unrestricted license. Releasing the planning document in this form will allow any number of third parties to create textbooks based on the core sequence. They can repackage it in their copyrighted content without paying any royalties or observing any restrictions in use. This allows authors of textbooks to develop and commercialise their intellectual property, while leaving the door open for other parties to publish content that uses the same schema.

Unlike CC-BY, CC0 does not legally require authors to credit the Medulla project for being the source of the core sequence. Instead I would simply encourage adopters to label their materials as Medulla-compatible for the practical benefit of informing their audience about the ease of using their materials in conjunction with other resources.

2. The document specifies a standardised sequence of core grammar and vocabulary to enable chapter-by-chapter cross-compatibility between resources.

My definition of chapter-by-chapter cross-compatibility would be this: there is no significant barrier to using material from another textbook.

A core grammar sequence outlining the major grammar points is fairly straightforward to imagine.

The core vocabulary sequence is less easy to foresee. It needs to be lean and not overly prescriptive, so as not to violate the principle below about freedom of subject matter.

Because courses must have freedom to introduce their own topical vocabulary on unit themes of their choice, there will still be a gap in vocabulary used between courses. This gap needs to be reasonably surmountable.

The current situation (as I will show in a future post about vocabulary) has students cramming the equivalent of over 10 chapters of words when switching courses at the exact midpoint. If this is reduced to levels comparable to learning about 2 chapters’ worth of vocabulary at the midpoint, it becomes a lot more viable to mix in outside materials or use textbooks interchangeably. In a future post I will outline ways we might achieve this with a reasonably lean vocabulary sequence.

3. Beyond the core sequence, the project aims to allow for maximal freedom of implementation. This includes such choices as pedagogical approach, story setting and subject matter, modes of delivery, use of L1, role of metalanguage, teaching of derivatives, etc.

The Medulla needs to be written in such a way that it serves a diverse range of textbooks.

I have seen examples of resources sharing the same sequence while implementing a very different pedagogical approach – Wheelock’s Latin has the reading supplement 38 Latin Stories, and Familia Romana has the grammar supplements Latine Disco (by Ørberg) and A Companion to Familia Romana (by Neumann).

The advantage of the Medulla project is that it can be purposely built for flexibility of approach, rather than just being a custom sequence devised for one textbook that is adopted by another author.

I do not believe it is suitable to use one of the 100-year-old public domain Latin textbooks as the basis of the Medulla project. The approach to grammar sequencing in hundred-year-old textbooks is often at odds with the pragmatic needs of reader-style courses that have emerged since the latter half of the 20th century. Furthermore, pedagogy continues to evolve and adapt in our generation and will continue to change in the years to come. Lifting a core grammar sequence from a century ago would require many modifications to satisfy modern expectations. We should instead start by developing a sequence that at least resembles our current textbooks, and better yet try to build in a degree of allowance for future developments in pedagogy.

4. The Medulla framework does not serve as an endorsement of textbook quality; it is designed solely for cross-compatibility. Responsibility for textbook quality remains with individual authors and publishers.

The Medulla is not an award or certificate of quality. The purpose of the core grammar and vocabulary sequence is cross-compatibility only. Because of the need for flexibility of implementation, it would necessarily be lean. The Medulla can only really control the sequence of major items of grammar and topic-neutral vocabulary.

Meeting the bare minimum requirements for cross-compatibility is different from meeting reader expectations of a fully fleshed-out, high-quality textbook. It is the task of textbook authors to decide how best to present the language in all its fullness and richness.

5. Community involvement is essential to ensure the framework is relevant, representative, and adaptable across contexts. We actively seek feedback from Latin teachers from different regions, demographics, and pedagogical approaches.

The community of Latin teachers possesses valuable knowledge about how textbooks really work in practice across multiple contexts. An individual Latin teacher such as myself can only directly experience a small piece of this bigger mosaic of Latin teaching practice.

For the project to succeed, it needs to be informed by this wider community.

6. The Medulla framework will be maintained with transparent versioning and changelogs, allowing users to track updates and ensure compatibility across editions.

As stated above in this blog post, the need for transparency, version control and public changelogs is part of why the project is hosted at GitHub rather than somewhere else such as Google Docs or WordPress.

I hope these summaries and rationale statements help clarify what Medulla is trying achieve. I look forward to sharing further updates on this project as time permits. Thank you to everyone who has contacted me so far offering their support.

-

The business case for Latin textbooks adopting the Medulla cross-compatibility standard

I am very pleased with the amount of feedback I have received on the Medulla project since first proposing it.

One person wrote in to ask why any new textbooks would take on a premade open source core grammar and vocabulary sequence rather than coming up with their own. After all, there would be no point in putting a lot of work into creating a shared sequence if there was no uptake.

Here’s a summary of my response: the business case for new textbooks adopting a single unified standard sequence.

When a new textbook appears on the market, it has to compete with established textbooks. This is an uphill battle because older textbooks are supported by large amounts of auxiliary materials, both public (in the form of published companion volumes) and private (in the form of in-house, teacher-created supplementary materials, which sometimes circulate between schools). Existing pools of resources are mutually incompatible between all textbooks, whether old or new. A newcomer therefore has to work very hard to be a viable, attractive alternative to older series, when switching to a recently published textbook means switching to a diminished pool of supplementary resources.

But if there existed a public domain standard code sequence, multiple new textbooks could team up to collectively create a larger pool of shared resources.

The choice facing every new textbook writer will then be this: do I commit to creating my own core sequence and locking myself into needing to create the first wave of support materials all by myself, while competing against established series that have much larger closed ecosystems? Or do I build on an open ecosystem which allows other textbook authors to expand the same pool of resources?

The first path is risky and labour intensive. There is no guarantee that even a very good new textbook can successfully convert enough Latin teachers to reach that critical mass where widespread adoption drives the creation of materials, and the availability of materials attracts more adoption. Before critical mass is achieved, the textbook faces a vicious cycle: lack of adoption means fewer resources are created for it, and a lack of resources means less adoption compared to bigger series.

The second path (building on a standard sequence) makes it possible for new textbooks to start with an advantage, and accrue more resources in both the short and long term. In an open ecosystem, supplementary resources would not just be made by the authors and adopters of one specific textbook series. Rather, every compatible textbook that enters would bolster the success of every other compatible textbook within the same resource pool. The resource pool would still need time to reach critical mass, but that time could be divided by the number of serious textbook projects that join it.

I have a lot more to say about this project, so stay tuned for updates on it on this blog.

-

The Medulla: A Proposal to Break Out of Closed Latin Textbooks and Create an Open-Source Curriculum

In this essay I will propose how we can create an open-source Latin curriculum, which I nickname the Medulla, or the bone-marrow. This curriculum can serve as the common core for a diverse new generation of Latin textbooks.

Have you ever daydreamed about writing your own Latin textbook from start to finish, knowing deep down that seriously, it would take far too much work to create and you’re not even sure where to start or if you would be able to finish it at all, let alone do as good a job as a big institution like the University of Cambridge?

I’ve indulged in that fantasy quite a lot over the years. I’m sure every Latin teacher has. I’ve probably started and stopped planning about three Latin textbooks and a Greek textbook, and so far I’m glad that all these projects have died in the ideation stage. But the desire remains.

And that desire keeps coming back as I realise that I have built years and years of my current curriculum materials around a sinking ship: the Oxford Latin Course.

Let me tell you about my predicament, and you tell me if it resonates with your experience.

Every year I am using the OLC is another year closer to the OLC becoming unusable by my students. The course was first published in 1987 with a substantially revised second edition published in 1996. There has been no further publishing activity since the 90s, so the textbook I am teaching from is now more than thirty years old.

Worse than that, it is now officially going out of print, with only a few booksellers stocking dwindling copies worldwide. Soon there will be no place it can be purchased, except in limited copies as used books. The global supply of OLC textbooks is non-renewable and diminishing every year.

However, the series is not out of copyright, and it will not be out of copyright until some 70 years after the death of Maurice Balme in 2012 – so I could start printing copies of it in 2082! If I am still alive at that time, I will be ninety years old.

I have been creating stories, interactive multimedia grammar tools, tests, exams, videos, and all manner of curriculum planning documents for this Hindenburg of a textbook since I started teaching with it in 2018 some seven years ago. I remember being given the option of switching the whole school over to the Cambridge Latin Course in 2018 but a colleague, who knew very little Latin, and who had learned to teach with the OLC just one year prior by keeping a few chapters ahead of the students, begged me not to switch to the CLC or he would have to relearn everything. He left the school maybe a year or so after, but by then I had sunk enough resources into remediating the OLC that I was now unwilling to move from it myself.

Now, seven years later, with the course going out of print, the school is pressuring me to move away from the OLC because of sourcing concerns. I’ve patched this course so much that my curriculum is pretty much more patch than cloth. I’m going to have to throw away the last seven years of my work and start from scratch with a new textbook, unless I can convince the school that the big class sets of library copies will be enough to keep the students resourced for the foreseeable future. It’s in a negotiation stage right now, and at any time in the future if those library copies start to go missing and supplies dwindle, we’re going to have this conversation again.

The purpose of this preamble is to present one of the practical problems of teaching Latin from the current model of textbooks. Latin, along with Classics and the Humanities in general, is contracting in higher education. There are fewer university-based institutions that have the resources to publish and maintain our existing textbooks. Unlike some modern languages, Latin does not get a whole set of newly minted products every year. We are forced to use aging textbooks because these are the only things available, other than what we make ourselves with our limited time and resources. You had better pray that your textbook continues to stay in print or you will have to throw out years of your work and make a big, wasteful switch to another textbook.

I’m sure every Latin teacher has gripes about the textbook they are using. There is no way that any single textbook can please everyone, but at least they substantially reduce the amount of work we would have to do if we wrote entire textbooks ourselves. The solution for most teachers is to stick with a course and create supplementary materials to customise it to your teaching style and your students’ needs.

But every textbook is a ticking time bomb. Every single one is copyrighted. I can almost guarantee that your textbook is already more than twenty years old, and that it will go out of print decades before its copyright expires. Some series are more active than others, but as the Classics in universities continue to contract, institutional support for aging textbook series is getting worn down thinner every year.

Enter my proposal: the open Latin textbook framework, the Medulla.

Currently every textbook contains its own unique sequence of core vocabulary and grammar. It is a closed system and any resources built around one textbook are only compatible within that one series.

What if we – that is, I and whoever wishes to form a working group with me for this task – created a core sequence of grammar and highly frequent vocabulary? We research Latin curricula around the world with the goal of creating a sequence that is compatible with as many school systems as reasonably achievable. We create the underlying structure, prioritising a sequence that allows for flexibility of implementation. We then release this core sequence as an open-source document.

Then, if the core sequence of our Medulla is well received by the global Latin teaching community, individuals and institutions can without restriction flesh this out into their own proprietary courses (or open source courses, if they have the funds to do so) that are nevertheless mutually compatible with each other because they all share the same open-source starting point.

There are multiple advantages to reducing barriers to entry and exit from textbook courses, advantages that go far beyond just mitigating the risks of books going out of print. I will show below how an open Latin curriculum such as the Medulla could allow teachers to experiment with different pedagogical approaches relatively risk-free, allow for student choice of themed units, allow for different teacher choices of textbooks within the same school, allow smoother transitions between turnover of staff at schools, and how this concept could greatly reduce the amount of duplicate work we are already doing as teachers.

Closed Textbooks, Untextbooking, and the Open Textbook

Let us outline the alternatives to my proposal: namely, to continue using copyrighted, closed system textbooks; to use public domain textbooks from 100 years ago; or to create a custom curriculum from scratch using novellas and teacher-created resources as in the Untextbooking movement.

At the moment, public domain textbooks from 100 years ago are very clunky to use in class. They often contain awkward political statements that have aged poorly, or simply do not provide enough input. I wish there were more recent public domain textbooks with more updated methods that were suitable for classroom use. But as it is currently, the best quality resources available to Latin teachers are proprietary textbooks. In the sections below I will discuss the limitations of both using and avoiding the use of our existing copyrighted textbooks.

Closed textbooks

Closed textbooks include proprietary courses such as the Cambridge Latin Course, the Oxford Latin Course, Ecce Romani, Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata: Familia Romana, and newer courses such as Via Latina and Suburani. I also include in this category grammar-translation style courses such as Wheelock’s Latin and So You Really Want To Learn Latin.

I have observed that often in schools, one Latin teacher is very determined to teach in a particular way while the other is determined to teach in the exact opposite way, and they have to marry their curricula together somehow. One teacher will insist on Wheelock’s Latin, for example, while the other will insist on Familia Romana. Or in my experience, the early years were spent in a mixture of So You Really Want To Learn Latin and Ecce Romani while the later year levels picked up from the Oxford Latin Course.

Or often there will be just one main Latin teacher in the school who retires or goes on maternity leave. The school then struggles to secure a permanent Latin teacher and hires a series of short-term replacements. Each replacement Latin teacher introduces a textbook change and erases the curriculum left by the previous teacher. The poor students switch courses, often multiple times, before a permanent Latin teacher finally gets them onto one course and stabilises the ship. (God forbid that teacher ever retires, moves interstate, or gets pregnant!)

It is very difficult to choose between textbooks when there are high points and low points in each. For example, I like how the OLCincludes myths from the Trojan Wars, and recounts historical events from the murder of Julius Caesar to the rise of Augustus. But I dislike most of the other stories in the textbook. Similarly, there are teachers who love the stories based on the eruption of Vesuvius in Pompeii in the first book of the CLC, but find the setting of Roman Britain pretty boring in book two (if you’re not teaching in the UK, the references to UK-based archaeological sites aren’t very relevant to your students). I like many aspects of Familia Romana, but I find the treatment of slavery and corporal punishment by the narrator repulsive. If only, I think to myself, if only I could just take some of the chapters of this book and mix it with the chapters of that book.

Closed textbooks make it very difficult for teachers to try new things. They force you to either commit to one system and stay locked in for years, or to expend a lot of effort and work switching to a whole different ecosystem.

But what about Untextbooking?

Untextbooking

Rachel Ash wrote an article in 2019 entitled, ‘Untextbooking for the CI Latin class: why and how to begin’. In it she describes her process of creating a curriculum without using pre-existing textbooks at all. She outlines how to choose a unit theme, how to select readings by adapting Latin texts on that topic, and how to create focused vocabulary lists based on those readings. The Latin texts could be adapted readings from authentic texts, taken from novellas, or written from scratch based on Roman or non-Roman contexts. The teacher sources, curates, adapts and writes these texts as well as creating all the activities around these texts.

She pulls no punches in describing how demanding this approach is on the teacher’s time.

I will not mislead you into thinking this is easy. It is extremely hard work. It is late nights, assessment, self-assessment, research, and cross-examination of your creations. It is checking your ego at the door because something you poured your heart and soul into, sure your students would love it as much as you do, was met with lukewarm feelings or even sarcasm. Untextbooking is teaching, but with even more of yourself invested into it.

When I read this, I think back to the first time I tried implementing a CI-based approach in 2022. I was passionate about changing everything, doing a root and branch renewal. I almost abandoned the OLC completely, but ended up just heavily supplementing the textbook with stories and CI-based activities that I was trying out for the first time. I used novellas and implemented a regimen of Sustained Silent Reading from those novellas. Everything that I could change, short of totally rewriting the textbook, I did change. I was ‘building the plane while flying in it’. I wanted to see what this would do for my Latin program.

I nearly burnt out that year. It was intense. I had nightmares and insomnia that got worse as the year progressed. I would break down crying if a relative asked me how work was going. I was frightened by loud noises. My ability to implement behaviour management in the class was seriously compromised. I started dreading going to work. I would drive to work and have to convince myself to step out of the car. I had to stay home the first day back after the school holidays, because of an overwhelming sense of panic. I used the services of a professional counsellor. The school relieved me of some of my more stressful classes while I recovered. I chose to change my working hours from full time to 0.8 for the next year to prevent burnout. I was seriously worried I might have to leave teaching altogether.

Thankfully, by drastically restricting the amount of schoolwork I did outside of school hours, and by going down to only four days a week of teaching, I gradually recovered.

Late nights of working around the clock to produce Latin texts that you also create activities for, on top of everything else a school teacher needs to do, are critically unsustainable.

I didn’t even go full Untextbooked and I could have permanently left teaching.

Burnout is not pretty. Teachers should be strongly warned against putting themselves in a position where they may have to work late hours into the night to keep their Latin program afloat. Textbooks are a lifeline because they allow you to go to bed at a reasonable hour, to cook meals, to spend time with your family and to not constantly be doing schoolwork.

I think Latin teachers are a very passionate group, and we love to create our own materials. But completely rewriting a course from scratch by yourself is a huge burden on any individual Latin teacher. That is why most of us use textbooks as a base and make small improvements – it allows us to work on updating our materials in manageable pieces.

I would also add that an Untextbooked curriculum suffers from succession problems. When that highly inspiring Latin teacher leaves the school, it is very likely that the next teacher struggles to understand the radical Untextbooked approach and finds it difficult to continue the sequence of learning where they left off, because there is no set sequence of what the students are supposed to have encountered by now. Every teacher making their own totally unique materials faces the same problem: how does one do a handover of a curriculum customised to yourself, if you need to go on maternity leave or move jobs?

Latin teaching is not just about cutting-edge pedagogy. It’s a profession where, for practical reasons, we need to work with colleagues who might have different approaches.

Both committing to a textbook and committing to going without a textbook are very big commitments. To experiment with new pedagogical approaches, it would be much better if you could just trial a new method for a few chapters and be able to switch back to your first approach if the experiment doesn’t turn out as you hoped it would.

Enter the Open Source Latin Curriculum, the Medulla.

The Open Textbook

Here is what I propose for the Medulla, in more detail.

A working group of teachers from around the world, representing each major curriculum region, collaborate to create a very stripped-down core sequence of grammar and highly frequent vocabulary that will serve as the basis for a new generation of textbooks.

The organising principle of this bone-marrow is to allow for flexibility of what can be made from it.

We decide on an arbitrary number of ‘chapters’: let’s just say 50 chapters for the sake of argument, but it may as well be 38, 54, or 47.

Each chapter is assigned core vocabulary and featured grammar. There is an effort made to spread the load evenly between chapters, so that there aren’t too many big spikes in difficulty.

Vocabulary

The core vocabulary focuses on functional words, not topical vocabulary. For example, any chapter 1 story could contain words like ‘est’ and ‘et’ and ‘in’. But topic-specific words like ‘aqua, fēmina, agricola, īnsula’ for chapter 1 are very restrictive and force people to write about water, women, farmers and islands in that chapter. The intent of a core vocabulary list is to provide common structure to support a diversity of implementation. If someone wants to write a course based on just stories from the Trojan War, they can. If someone wants to write an ecclesiastical Latin course based on bible stories, they can. If someone wants to write historical fiction set in Rome at the time of Cicero, they can. If someone wants their stories to be about a time-travelling school bus, they can.

The core vocabulary could be based on frequency lists such as the DCC top 1,000 words, but it need not include every single word in a list of 1000. The purpose is more to provide a baseline for introducing functional words so that students don’t miss out on them. I have recently taken over a cohort of students who were learning from Ecce Romani and they hadn’t yet encountered a very common word: ‘-que’. The OLC barely ever uses the extremely common word ‘vel’ and hardly ever uses ‘fuit’ or ‘fuērunt’, overusing ‘erat’ and ‘erant’ instead. Many newly written Latin materials present a language shorn of discourse particles such as ‘enim’ and ‘vero’, because of the desire to keep unique word counts as low as possible. Functional words like these are everywhere in authentic Latin texts, and will be important no matter what topic the student wants to eventually read about. Students need lots of exposure to these functional words spread throughout their learning journey.

Grammar

The core grammar sequence provides a guideline for when each major item of grammar is featured.

Anyone intending to create a textbook based on Grammar-Translation or the Reading Method will readily understand the usefulness of a sequence of grammar topics, but what about people aiming to implement a more purist CI approach that eschews grammar sequencing entirely? To them I say, if anyone wants to write a purely CI Latin curriculum that includes all grammar from the beginning, they still can do this and freely include ‘advanced’ grammar in their earlier chapters. They just need to provide feature-worthy examples of the target grammar in the target chapters. That is, they need to allow circumstances for pop-up grammar lessons to occur in the agreed chapters. The sequence of grammar is a guideline that allows for easy entry and exit between courses, and the presence of ‘advanced’ grammar sneakily incorporated in earlier chapters is not a barrier to readers either entering or leaving a course.

The working group needs to include representatives from each region of the globe where Latin is currently taught in high schools. The goal is to create a sequence which is compatible with the largest number of pupils under the current curriculum conditions. The representatives need to research their local curriculum requirements and report what the hard limits are for each schooling region in their care. For example, does your school district require all noun cases to be introduced within a certain amount of time into the course? If there is a small region which is extremely prescriptive, we may need to make a pragmatic decision not to accommodate that curriculum, in order to accommodate more pupils worldwide.

There are known debates about the sequencing of grammar, such as whether to introduce declensions 1-3 together and learn the cases one at a time, or whether to learn all the cases for declension 1 first, then learn declension 2, then declension 3. The guiding principle is still to create a curriculum which is the least restrictive for the most people. For the example mentioned above, introducing all three declensions at the start does not prevent teachers from creating Grammar-Translation textbooks, nor does it prevent teachers from teaching full declension chants from the beginning before all the cases have been met in context. However, withholding declensions 2 and 3 severely restricts the types of stories which can be written in the early chapters to the world of islands, women, farmers, and water. Therefore it should be preferred that all three declensions are introduced early, for the sake of allowing a greater diversity of pedagogical approaches.

It may be objected that some grammar topics (gerundives, for example) are only difficult because they are introduced so late. To this I say, the grammar topic sequence is for dividing up time so that there is enough time to give focused attention to each topic. If gerundives are one of the last things to be officially focused on, they can (and should) still be ‘snuck in’ to earlier chapters and glossed as necessary. A language contains many grammatical topics, and so if there is any spotlighting of grammar at all, some items must have their time in the spotlight later than others. This does not mean they should be saved up to the last possible moment.

Next steps

My proposal is that we form a working group that includes Latin teacher representatives from around the globe. We assign curriculum research tasks and share our findings. We take stock of the curriculum restrictions in various regions. Then we hash out a draft curriculum. We present the draft of the Medulla for feedback and review by Latin teachers worldwide. We make edits to the curriculum. We publish a finished document in the public domain.

Only after the Medulla has been well received does anyone start writing an implementation. Because the structure is public domain, anyone anywhere can develop a textbook based on this structure without restriction.

Advantages for using the Medulla

Institutions can use this structure as a starting point, knowing that it will be compatible with as many regional curricula as possible, meaning they can sell textbooks globally. They can also proceed knowing that the structure has the vote of confidence of the general Latin teacher community.

Circling back to what I said at the beginning, pretty much every Latin teacher has a dream of writing their own course. Now they don’t have to do any duplicate work in the planning stage. You could take your ideas and start writing just a few chapters if you wanted to. If you primarily teach the lower years, you could just create the first 10 chapters and stop. If you primarily teach upper years, you could just create the final 10 chapters. No one has to commit to creating an entire Latin textbook structure from scratch, just to get their ideas on paper.

If anyone wants to create themed units, they can. They don’t need to create an entire Latin textbook to make 5 chapters that focus on Gladiators and Chariot Races. Teachers could allow students to vote for their favourite topics and then create short unit-based resources that just span a few chapters.

If anyone wants to create a course entirely based on tiered readings from authentic texts, they can, and just need to include some feature-worthy examples of the target grammar for each chapter so that each topic is given enough spotlight.

If a school wants a teacher to create their own in-house resources, they can do so in stages, while using another resource for teaching. For example, a teacher could use a proprietary course, but just write 5 chapters of their own per year. After 10 years they’ve written 50 chapters, and little by little the entire course has been replaced.

The work could also be shared between teachers at the same school – one teacher can pick up the task where the other teacher left off. If one teacher leaves the school before finishing writing a textbook, it is obvious what parts they have done and what parts remain.

The approach in general allows easier handover between teachers. If one teacher leaves and a new teacher is hired with different tastes and styles, the next could choose to switch to any number of proprietary courses that run the gamut of Grammar-Translation to CI approaches, without breaking sequence.

If there are two teachers at the same school who have wildly different approaches to teaching Latin, each of them could adopt textbooks that apply different teaching methods to the same framework and students would be able to move from one teacher to the next relatively seamlessly. (This is not the case when a student leaves a course halfway through Familia Romana and moves to Wheelock’s, or vice versa!)

If a teacher wants to try a different pedagogical approach, they can do so for just a few chapters, and know that they can safely switch back to their more familiar style if it doesn’t suit them to continue.

Researchers would be able to make A/B tests of Latin curricula. A cohort of students from the same school could be divided randomly into two groups, each of them studying from a different approach but covering the same material. Through this, it would be easier for us as a profession to learn more about the effectiveness of different pedagogical approaches.

Final encouragements

I am passionate about improving Latin teaching, but the older I get, the more I realise how complex the situation is. As findings from Second Language Acquisition research come to light, what is considered ‘best practice’ today will not necessarily be best practice tomorrow. Meanwhile, within the traditional suite of Latin teaching practices, I am sure that there are hidden gems, kernels of wisdom that are not yet fully understood or appreciated by the younger generation of more CI-minded teachers like myself.

My goal in proposing a Medulla, a deeply rooted bone-marrow at the core of a curriculum, is not to impose change on the unwilling, or to restrict the development of new methods. It is to free all Latin teachers from the unnecessary burdens of duplicate work, of labouring alone in our siloes and making dead-end resources for closed textbook courses that are inevitably going to go out of print.

But I cannot do this alone. I need representatives who know the curricula of their region and are willing to lend their time in research and development of an open framework that allows us to break out from working in just one textbook ecosystem at a time.

Until we do this groundwork, we are bound to continue making closed courses and an endless number of proliferating incompatible systems.

At the current moment, every textbook is its own island.

If we created an open framework and just two decent textbooks came out of this in the next generation, this would be the first example of a pair of complete, mutually-compatible textbooks that teachers could freely move into and out of.

If you believe your expertise can help in this, please contact me via my contact form and I will arrange for a working group for the Medulla curriculum to be formed, and sketch out the tasks and timelines for us.

In your email to me, please include your name and:

- What is your location?

- Is there an official Latin curriculum (or several) in your region that mandates the teaching of grammar or vocabulary at certain stages?

- Tell me a short summary of your experience in teaching Latin, and your general approach to teaching Latin.

I will aim to create a working group that is not too large but still representative of diverse regions and approaches.

I will be collecting expressions of interest for the next month, October 2025. If you can please share this call for help with other Latin teachers, especially in more remote regions of the globe, that will be helpful too.

Curāte ut valeātis.

Carla

-

We need to talk about Latinitas.

We need to be allowed to talk about Latinitas in the context of Latin teaching. What follows is a 7,000 word explanation why. In the course of this essay we will explore the effects of mandating a veneer of public positivity about CI Latin novellas and why this is problematic. As a community we need to be able to face uncomfortable discussions and question whether our current practices are helping or harming fellow teachers.

As a very brief definition, ‘Latinitas’ is the quality of Latin writing which reflects the character of the Latin language. Just like in any language, it is possible to write a grammatically correct sentence which is awkward or unnatural sounding. In Latin discussion, unidiomatic phrasing might be called ‘bad Latinitas’, while idiomatic word choices might be called ‘good Latinitas’. I will unpack the fuzziness of defining Latinitas and critique the moral overtones of these labels later in the essay, but this very rough definition is a reasonable place to start.

I’ve been intending to write this essay for several years but stopped many times as my views on the topic have changed considerably. Now I feel that I cannot continue to stay silent about the issue due to the wider harms it is causing our community.

This essay is motivated by a long term trend, not strictly written in response to a recent incident in which a commenter was banned from the Latin Teacher Idea Exchange Facebook group after posting comments on this topic.

An earlier version of this essay contained de-identified screenshots and quotes from the incident. I hadn’t realised until after posting that this violated the community rules of the LTIE facebook group, but once I was notified, I took the post down and have now edited out all screenshots and direct quotes.

I mentioned this incident because some people say they have never seen an example of community rules being invoked to silence discussion of language quality in published teaching materials. This is a single instance of a broader and usually more well-hidden phenomenon.

A person whom I renamed ‘Red’ posted three comments about novellas in response to an unrelated thread about AI-written Latin materials. This commenter claimed that Latin novellas had been of highly questionable to simply low quality (paraphrasing, since direct quotes are banned – but this commenter did not use any profanity to describe Latin novellas, nor did he name any specific novella or author). Other commenters in the thread then escalated the tension, such as by labelling Red’s opinion as crap. In Red’ third comment he denied his opinion was crap, and said that the person who had called him that did so because he was unable to judge novella quality.

A moderator then posted a comment saying they had now banned Red from the LTIE facebook group. When I asked for clarification in that thread whether he was banned specifically for the three comments, the reply was that Red’s comments had violated the group rules of maintaining a protected space and being kind and courteous, which would normally simply result in a reminder of rules, but in this instance Red had been banned for a larger pattern of behaviour beyond these three comments. Nothing was said about the comment calling Red’s opinion crap; using the crap-word was not publicly said to be a violation of a kind and courteous space. (However, giving moderators the benefit of the doubt, perhaps the commenter was privately messaged a reminder to be kind and courteous next time – I would not know.)

I do not have any dispute with moderators making decisions to ban someone in any particular instance, since moderators have information about the wider situation which I do not and should not have. Red was also derailing the original post. When I say that this issue is harmful, I am not talking about harm done specifically to Red, but harm done to the community as a whole, including the authors of novellas.

My problem is with the manner in which the emotions in this thread were allowed and encouraged to escalate, and what that suggests about our community. Red did not actually say ‘Latinitas’, ‘Latin style’, ‘word choice’, ‘editing’ or ‘idiom’ when he spoke of low or bad quality in novellas. He left it vague. But even saying that novellas were of bad quality while mentioning no specific authors or books was enough to make the community react very strongly, sending a message that the community believes it’s okay to say the equivalent of ‘this is crap’ in response to someone saying the equivalent of ‘these are bad quality’, but not okay to say the equivalent of ‘these are bad quality’ when one refers to novellas.

What surprised me most about this incident is that it happened on the Latin Teacher Idea Exchange, not on one of the CI-based Latin teacher facebook groups. The LTIE is larger and regularly posts a more diverse set of views about pedagogy than the more specialised CI Latin facebook groups – you will find people sharing grammar translation resources as often as CI resources. It should be expected that people have differing views about the quality of pedagogical resources, even simply from the fact that not everyone shares the same pedagogical frameworks. But novellas, it seemed, were to be considered immune to criticism.

This is part of the worrying trend I’ve been noticing, now not just in CI Latin circles, but even in general Latin teacher circles: namely, you are not allowed to put forward the opinion that Latin novellas are ‘bad’. You are not allowed to write a public comment that you think you found a specific mistake in a Latin novella, or that you think a novella has multiple errors per page, or even just that novellas in general have errors. Instead, a series of arguments are enlisted to silence public criticism.

In this essay I aim to examine and refute the arguments used to silence criticism and discussion.

What I will not be refuting is any argument that already starts with the proposition that the Latinitas of novellas diverges from classical idiom. For example, it could be argued that pedagogical materials do not need to be written strictly according to the target language dialect, because they represent transitional learner-focused language. This argument does not require anyone to conceal differences between the language of a novella and the target language, but instead argues for acceptance of a different dialect created for classroom use. This discussion is only possible if we can acknowledge when and where there is a difference between the idiom of Latin novellas and standard Latin. Until we are allowed to claim that there really are noticeable divergences in idiom, the discussion over whether such divergences are beneficial to teaching cannot proceed.

Likewise, it can be argued that some authors are not given adequate resources to reliably vet the Latinitas of their works when self-publishing. There is an inequality in Latin education where some Latinists were given rigorous training in Latin prose composition, while others were not. There is an inequality in wealth distribution where some Latinists are willing and able to pay for professional editing services, and others are not. There is an inequality in professional connections where some Latinists are able to pitch their ideas and publish texts through major traditional publishers who then provide the editing services, while others do not think they have a chance of being traditionally published. We should acknowledge and aim to address these structural problems. Unfortunately, we cannot advocate for structural change in favour of CI when we are not even allowed to claim there is any problem with the current quality of self-published CI.

So let me be clear: I am not, in this essay, going to discuss whether all the claims about ‘bad Latinitas’ are valid in all instances, or whether a Latin teacher is obligated to avoid modelling ‘bad Latinitas’ to students at all times. These are derivative arguments. I am instead focusing on the issue of whether mentions of perceived errors in published works should be allowed in public comments. Without being able to hash these things out in the open, the derivative arguments about the degree of Latinitas issues and the usefulness of pedagogical language choices simply cannot be discussed fairly. If we want to give teachers the freedom to choose where they stand on issues of dialect choice, we need to be able to talk about the dialect itself, with specific examples if needed. The problem is that we are not allowed to talk straightforwardly and honestly about our perceptions of the editing quality and language use in self-published novellas.

Here is an example of a CI novella resource advising the community that public comments or rating of Latinitas should be discouraged. The Latin Novella Database (LNDb) appears to have started in 2020, with the earliest novella news post dating to March/April of that year. According to announcements on social media, it ceased to be updated after 2021. The LNDb remains accessible to this day as a resource. One of the pages linked in its side navigation is titled, ‘What about Latinitas?‘. I remember reading this page in 2021 when I had just woken up to CI and was first looking into implementing Latin novellas in my teaching, and I remember agreeing with it wholeheartedly at the time, taking these points in as speech rules for the community and for myself. I have chosen to critique this page precisely because I have no idea who authored it, and I do not want to know who authored it – my dispute is not with any individual, but with the culture of our community.

WHAT ABOUT LATINITAS?

LNDb does not, and will never, give ratings of the supposed Latinitas of the novellas, and it’s something that people shouldn’t be worrying about.

- What other teachers have written works for them and their students. When you see a bit of Latin that doesn’t seem right to you, remember: it wasn’t written for you. This teacher wrote it for their students, and even if it doesn’t suit your needs, it suits theirs. Respect that.

- Unsolicited criticisms of Latinitas don’t educate; they embarrass and degrade. They only make the corrector feel superior and the correctee feel inferior. This is especially true if they’re of a group that has been historically shut out of Classics study (e.g. women, POC; cf. mansplaining)

- You may be wrong. Or both of you may be right. In reading all of these novellas, and [sic] many times I thought I found a little mistake in Latinitas. Yet most of the time, it was I who was incorrect. You know Latin, but they know Latin too. Respect that.

- “Good Latinitas” is an unknowable construct. While you can make assumptions based on the corpus of Latin literature on what constitutes proper Latin, these are only assumptions. Unless you have regular séances with Cicero, you don’t know better than any of us.

- If it doesn’t work for you, make your own. Martial 1.91:

Cum tua nōn ēdās, carpis mea carmina, Laelī.

carpere vel nōlī nostra vel ēde tua.Point number 1, ‘What other teachers have written works for them and their students’, is a derivative argument. It assumes the possibility of a dialect difference: that if the Latinitas of a novella diverges from classical idiom, a teacher should still be allowed to choose it as class material. This is a separate argument as to whether it is acceptable to publicly talk about the classical Latinity of novellas. Talking about Latinitas does not restrict individual choice. Rather, silencing discussion about the dialect limits the opportunities for teachers, especially those new to CI Latin, as I was in 2021, to make informed choices. I will not refute the derivative argument that it is up to the teacher to choose materials which suit their needs. Rather, I disagree with the way this point is used to silence discussion of Latinitas: respecting individual choices means providing teachers with the best opportunities to make informed choices. Talking openly about what is divergent about the idiom of Latin novellas allows for people to draw their own conclusions.

Point number 1 also assumes something dangerous: that published materials are actually developed only for the author’s specific classroom. I will explain why this is a dangerous position to hold below, but for now let us allow that there might be pedagogical reasons for divergences in dialect.

Point number 2, ‘Unsolicited criticisms of Latinitas don’t educate; they embarrass and degrade,’ characterises criticism of Latinitas as ‘unsolicited’, ’embarassing’, and ‘degrading’, intended to make the corrector ‘feel superior’ and the correctee ‘feel inferior’, and aimed at people who have experienced structural inequality. I will examine each of these characterisations and their implications.

Comments that include Latinitas criticism are characterised as ‘unsolicited’. This is a very strong word to use for replies to public posts about the content of those posts. If I post a YouTube video and someone writes a detailed comment about, say, my skin, I would readily call that an ‘unsolicited’ comment. Any comments about my physical appearance or personal life are ‘unsolicited’ because these things are not the focus of my content. Similarly, Red’s comment above can be considered unsolicited as it was derailing the actual topic about AI Latin posted by the OP. But if someone comments about my language choices in response to one of my language teaching videos, that is a different matter. I may not agree with what they say, but they are responding to my content, part of which includes my language choices as a language teacher. Someone talking about what I posted is not an ‘unsolicited comment’, it is a ‘reply’.

If comments about language choices on language teaching materials are ‘unsolicited’, what comments if any are truly ‘solicited’? Only comments that do not include dialect-based criticism? Only 100% positive comments? Or are there no ‘solicited’ comments – when authors post their work in a forum or on facebook, do they not wish to get comments at all?

If a comment is only ‘solicited’ if it is not about Latinitas (e.g. someone says that they didn’t like the character development in a novella, or that the pacing was too slow, or the font was too small or big), this seems like a pretty strange definition of ‘unsolicited’ if the author is willing to hear criticism about other aspects of their creative process and is selectively unwilling to hear about their wording choices, which are also part of their writing process. As was alluded in point number 1, authors and readers care about the pedagogical implications of their phrasing. It cannot be argued in point 1 that phrasing is a meaningful pedagogical choice if it is also argued in point 2 to be irrelevant and off-topic to the discussion of a language teaching resource.

If a comment is only ‘solicited’ if it excludes criticism, what does that say about the nature of our community? Part of being in a community is being able to communicate with each other. Do we expect only to hear communication on what we are doing well? Are we supposed to never hear any negativity or disagreement? Does that constitute a genuine community? How could you trust that people are not lying to you to make you feel better? How could you trust that people aren’t pretending to say nice things when they should be warning you against doing something you might regret? What does praise even mean, if criticism is not allowed? The idea of ‘toxic positivity’ comes to mind: it is a damaging mindset in which all difficult emotions are deemed ‘negative’ and all negativity must be avoided. Toxic positivity blinds communities and makes it impossible for us to address issues openly.

If no comment is truly ‘solicited’ (because it comes from a person on the internet typing in the public comments section), why not make intentions clear by disabling comments entirely? If a writer does not want to see any ‘unsolicited’ comments, why are they posting in places where comments are not just expected, but encouraged as part of community engagement?

Publishing in itself is a communicative act, and so discussion about the writing choices in published works should not be considered ‘unsolicited’. If an author wants to protect a work from public comment, they can choose to share it among friends or private groups, or just use it with their own students. It is completely appropriate for a high school teacher to focus on only serving their own students – anything more than that is actually going beyond their job description. But by publicly sharing their work, they are communicating with the public through it, saying ‘here, this is a Latin language teaching resource’, implying that it should be used as teaching material outside of the author’s own classroom, or as an example to inspire the creation of similar resources outside of their school. Responses to the book from teachers outside of the author’s school are to be expected, because the author has already entered into public discourse through publishing the work outside of their school.

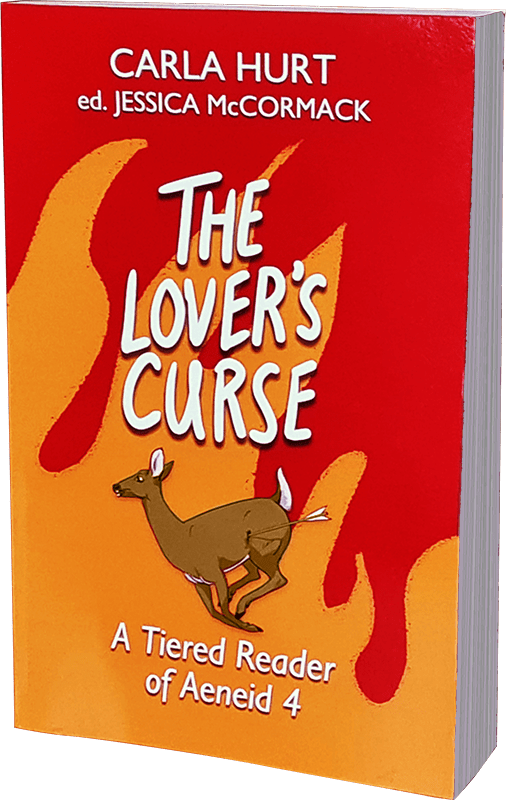

This is not just a matter of custom, it is a matter of law. Employment contracts typically include a legal clause where they prohibit teachers from publishing curriculum materials developed for their school, stating that the intellectual property in this instance belongs to the school. My own state of Victoria rules that ’employers own IP in materials created by employees in the course of their work,’ [source] and this is reflected in US copyright law as well: ‘A copyrightable work is “made for hire”… [when] it is created by an employee as part of the employee’s regular duties,’ in which case ‘the party that hired the individual is considered both the author and the copyright owner of the work.’ [source]. Thankfully my employer congratulated me when I published my book, The Lover’s Curse: A Tiered Reader of Aeneid 4, although they technically had IP rights to early draft sections created in the course of teaching year 12 in 2022 (patchy sections which would have been unsaleable until I created the rest of the book and independently organised its editing and further development, making it substantially improved from the excerpts I used in class).

Legally, teachers should be advised that their book publishing projects need to be separable from their regular duties as teachers creating in-class material, or else their employer owns their IP. By publishing their IP outside of school, teachers need to acknowledge that they are acting as independently published authors, and not as regular school teachers. Thus, interactions with the public world outside of their school should not be considered ‘unsolicited’ but expected: publishing is not a normal part of teacher duties, it is an action that involves you putting your IP into the public sphere of communication and claiming it as your own.

Based on the way our community is reacting to public comments on novellas, I don’t think we are doing a good job at educating teachers about the legal reasons we need to distinguish our role as teachers from our role as authors. Legally, we need to accept that being a published author means investing independently in developing our own IP outside of normal school duties. What this doesn’t mean is sharing un-edited resources developed in the course of our regular duties out of ‘generosity’ (which would violate the IP of our employer). The scenario described in point 1, where a teacher publishes materials developed solely for their own class without any modification or consideration for an external audience, is technically copyright theft.

This may, in practice, be unlikely to be prosecuted. Schools, when run ethically, usually do not care about teachers publishing materials. However I have had the unfortunate experience of being hired by an unethical boss once before. I have had the experience, in a different school to where I currently am, where senior leadership were looking for ways to catch teachers for minor infractions in order to threaten their job security and control the staff by fear and punishments. Most schools are not run like that, but for some teachers, it is possible to get burned by one’s employer or ex-employer over legal technicalities.

But getting back to the larger point, teaching and publishing are legally distinct industries and involve different roles. It would be out of place to see regular teachers criticised in public for simply doing their regular teacher duties in school. But it is part of the role of a published author that their work invites public discussion. Legally, publishing is not part of the regular duties of a school teacher and organisations could be making themselves liable for encouraging copyright theft if they encourage publication without mentioning this distinction.

For this reason, while we can offer writing advice for in-class materials, perhaps we should not be offering instruction for publishing novellas as part of teacher training and teacher conferences. We could bring in experts from the publishing industry to give talks about publishing, and encourage interested teachers to attend, but these should not be counted as official teacher training hours, because publishing is not part of the regular duties of a teacher. Our teacher training PD should be focusing on the creation of classroom resources strictly for use within the school. Professional development in publishing is a separate venture which should be performed by experts in that industry and according to those industry standards.

When you communicate, you are agreeing to possibility of relevant communication in response. To be clear: you are not consenting to receive unsolicited comments about your physical appearance or personal life or any other irrelevant topic. But by posting something, you invite comments on the specific topic which you posted about: if this topic is your own work, you invite comments on your own work. And by publishing, you participate in the publishing industry and are expected to act as someone who has communicated publicly through their own independently developed work.

Next, criticism of dialect is characterised as ’embarassing’ and ‘degrading’, making one feel ‘superior’ while another feels ‘inferior’. I will point out that point number 1 already assumes that dialect differences can be pedagogically justified. If this is the case, why are these justifiable pedagogical decisions ’embarassing’ or ‘degrading’ to the person who chose them? Should we be embarassed by our pedagogical choices? Say someone ridicules me for using spoken Latin in the classroom, saying that this is ‘just Roman LARPing’ in an attempt to degrade and humiliate Latin speakers and make them feel inferior. Is any Latin speaker genuinely embarassed by such an ignorant comment? Rather, I am embarassed for the person making such a comment. Why, if authors are proud of their pedagogical dialect choices, should they feel ’embarassed’ for having made those conscious language decisions?

In all seriousness, I understand what is felt here, and that it is a genuine and deep-seated hurt. People do feel ‘inferior’ when they are told that their Latin writing might have areas for improvement. I want to validate that feeling, because it is a natural response to the way Latin has been presented to us in schools: ‘if you are good at Latin, you must be smart, so if you’re bad at Latin, you must be dumb.’ I don’t think anyone can be blamed for feeling inferior when their Latin is not perfect, after so many years of that lie being conditioned into us.

But my question is, how should we respond to our feelings of inferiority? Should we allow ourselves to continue believing the lie that we are ‘dumb’ if our Latin is ‘bad’? I think we owe it – not to our critics but to ourselves – to separate our sense of worth from our work. We need to replace the old lie with a new truth: no one’s self-worth should be based on their competence in Latin. There are many horrible people who have ‘good Latin’, and many wonderful people who have ‘bad Latin’. As a community, we should encourage each other and ourselves to see that criticism of Latin style is not a criticism of one’s character.

The point stating that ‘criticisms of Latinitas… embarass and degrade’ goes part of the way towards acknowledging the hurt that exists. This is good, to an extent. We should take it one step further, towards a message of healing: ‘criticisms of Latinitas feel embarassing and degrading because of years of previous conditioning, but we need to affirm now that no one can judge character based on Latinitas. These two things are not the same.’

If we can un-couple criticism of Latin style from condemnation of character by affirming each other’s worth while talking about possible strengths and weaknesses in their writing, we can rewrite the script and heal from the harmful lies of our past. This long journey of healing is not possible if we always avoid confronting the lies, by making speech rules which freeze short of correcting a moralistic attitude that we know is false. Ruling that criticism doesn’t educate but only shames will only continue to conflate Latinitas with character and prohibit us from talking about our work as something separate from our worth.

Lastly for point number 2, the LNDb mentions that the experience of structural inequality is a factor in determining who corrects and who is corrected. I would argue that structural inequality impacts many other aspects of writing too: the degree to which we receive instruction on constructing characters and plots, our familiarity with Greco-Roman myths, our networking skills in finding editors and in being accepted by traditional publishers. There are many ways in which structural inequality unfairly impacts the quality of our work in ways we will never be able to precisely measure or appreciate. It is therefore the responsibility of the structurally privileged to share their knowledge and skills with the structurally disadvantaged, and for us all to advocate for community practices which reduce the gap between the haves and have-nots. But we cannot advocate for change if we are not allowed to mention any problems with current practices.

For this very reason, the people who care the most about the structural inequality of academic Latinists correcting the Latinitas of high school teachers should be the most interested in collaborative efforts which can bridge the skill and resource gap. We cannot protest the skill and resource gap unless we acknowledge that there is an inequality of outcomes in the quality of self-published CI Latin materials versus traditionally published Latin materials.

Point number 3 states that a commenter ‘may be wrong’, or ‘both of you may be right’.

So what if a commenter is wrong? Correct the commenter, or let someone else do it, or let it go. People can be wrong about anything in a comment. You can’t prevent people from having wrong opinions, but you can give opportunity for wrong opinions to be voiced and then corrected in community discussion. If a commenter is wrong in a public forum where they are corrected publicly, they are not a lasting threat to an author’s reputation; at most they are an embarassment to themselves.

I don’t think anyone reads comments sections believing that every commenter is a reliable source. If we ban topics because sometimes people comment on them wrongly, we would have to ban every topic from discussion.

Point 3 also urges us to respect that ‘you know Latin, but they know Latin too’.

Respecting other people’s knowledge of the language means believing that they are confident about what they do and don’t know, that they care about further improving their use of the language, and would be more than capable of answering back if you were wrong. When you respect someone as being strong in the language, you approach topics with them gently and warmly with an attitude of shared curiosity, not condemnation. You are open to being persuaded by their views, and are curious as to how they might respond to your views as a fellow enthusasiast.

The following attitude is not ‘respecting that they know Latin’: assuming that the other person is so weak in their Latin that they will be devastated by the slightest suggestion that they wrote something wrong. If you instead assume that the other person is strong, it follows that they should be open to talking about their use of the language, or if they’re busy, they would be fine with ignoring you and leaving others to correct you. You should fear more for embarassing yourself than embarassing them in talking to a strong Latinist.

Criticism can be offered respectfully to competent Latinists. The need to respect someone doesn’t prohibit you from talking them about their work, but on the contrary, respecting someone’s expertise allows for a candour that would otherwise be more difficult with someone whom you knew was more self-conscious about their Latin.

Point 4 states ‘”Good Latinitas” is an unknowable construct’. In support of this, it argues that the assumptions we make about usage based on the classical corpus will always be, to some extent, assumptions. It then denies that anyone can hold better or worse assumptions than another, stating, ‘Unless you have regular séances with Cicero, you don’t know better than any of us.’

Some of the propositions are true, but the conclusion is flawed.

I will certainly grant that ‘good Latinitas’ has fuzzy edges. Should the features of Silver Latin be counted as ‘good Latinitas’ on par with Golden Latin? Should historically attested post-classical Latin idiom be excluded from ‘good Latinitas’? Should ecclesiastical Latin be avoided? Should the linguistic quirks of Plautus and Terrence’s much earlier form of Latin be included or excluded? There are worthwhile arguments to be made around the definition of ‘good Latinitas’, especially depending on whether you are writing in prose or poetry, high or low register, secular or religious texts, for absolute beginners or for advanced Latinists.

The Latinitas of self-published novellas should most appropriately be compared to the Latinitas of educational materials in general: Familia Romana, for example, would make a much better benchmark for language style in novellas than unadapted Cicero. While there is a massive difference between the register of Cicero and ‘Rōma in Italiā est’, practically no one takes issue with the Latinitas of Familia Romana in carrying out its educational purpose.

However, I would argue that classifying Latinitas as ‘an unknowable construct’ imbues it with more mystery than it deserves.

Perhaps ‘standard Etruscan’ or ‘standard Eteocretan’ are an unknowable entities. But ‘classical Latin’, according to how finely or coarsely we wish to define it, is at least an observable phenomenon, and anything you can observe you can to some degree ‘know’.

Point 4 itself states that there is a corpus of classical works from which we can make assumptions about the dialect. One way is to search the corpus for phrases and check whether such phrases are used to mean what we think they mean. Another way is to read large amounts of the corpus and so develop an intuitive understanding of the language habits of those writers. Another way is to consult composition manuals and reference works compiled from that corpus – of which there are many, such as Meissner’s Latin Phrase Book – for practical advice gathered from other people’s experience in replicating classical idiom. The fact that Latin prose composition courses can be taught and formally assessed at all suggests that there is a standard language which we can learn to write in, and even be given a grade for. (‘Rating’ Latinitas is exactly what the teachers do in a composition course!) This is a standard practice in continental Europe. Latinitas may be fuzzily defined, but we do have a body of evidence from which we can observe and study it.

Next, let us grant the second statement, that our knowledge of Latinitas will always be incomplete. This is an appropriate stance to hold. We can draw assumptions about the language from what we observe in the classical corpus, and these can be called assumptions. We should be willing to consider that our assumptions, even the best ones, might be false.

What does not hold up is the conclusion: that there are no better or worse assumptions.

Just because perfect knowledge cannot be attained, it does not follow that all assumptions should be considered equally valid.

Imagine if we applied this same reasoning to other topics:

‘Scientific knowledge cannot be proven indisputably; therefore no person has a better understanding of science than anyone else.’

‘Fun is an unknowable construct. We can only make assumptions about what is fun. Therefore, no one can advise on how to plan fun Latin lessons.’

‘All knowledge is ultimately impossible to prove. We can only make assumptions about it. Therefore no one knows more than anyone else.’

This line of reasoning excludes the possibility that there can be degrees to which claims are based on evidence: relative probabilities. Some claims may be based on outright misunderstandings, some on weak evidence, and others on stronger evidence. The strongest claim can still have some degree of uncertainty, but that does not mean all claims have the same degree of uncertainty.

We should be open to the possibility that we are wrong, but aim to arrive at the most probable answer. This is a lot easier when we can talk openly about our hypotheses and share our experiences with the language. I have learnt so much more about Latin usage through talking with other people about the word choices I made in my language teaching materials. Commenters can and do comment incorrectly about word choice. But banning discussion about word choices is not a good method for discovering the truth. As a community, we are more likely to arrive at a better solution when we are allowed to talk things through.

For this reason, because Latinitas is a complex topic, we should want to hear multiple perspectives about it before settling on a conclusion. ‘Good Latinitas’ is a fuzzy, intricate, contextually murky, and yet beautiful phenomenon. It is the nature of human languages to have their quirks and hidden treasures. This is part of the joy of studying natural human languages in contrast to constructed languages. Every language is different in surprising ways. We can appreciate that diversity and strangeness better when we talk about it together, approaching it with an attitude of curiosity and wonder instead of seeking merely justification and expedience.

The fifth and final point states, ‘If it doesn’t work for you, make your own’ and quotes Martial 1.91, which I translate below:

Cum tua nōn ēdās, carpis mea carmina, Laelī.

carpere vel nōlī nostra vel ēde tua.While you do not publish your own poems, you disparage mine, Laelius.

Either don’t disparage mine, or publish your own.It is for this reason that I waited years before writing up an opinion about Latinitas. I knew that unless I published my own Latin educational text, people would not take me seriously for speaking out about this topic. Well, my tiered reader for upper high school, The Lover’s Curse: A Tiered Reader of Aeneid 4 came out in September last year, 2023. My editor Jessica McCormack and I are very pleased to see that it is being enjoyed by students around the world, making Vergil’s poetry more comprehensible to more readers.

The book has enjoyed a positive reception for its illustrations, its clarity of Latin explanations, and – importantly for this topic – its overall writing and language quality.

I could not have achieved this language standard without hiring a professional editor. Indeed, the only reason that more mainstream CI Latin textbooks such as Familia Romana, Via Latina, and Forum (by Polis) are so much more standard in their use of Latin than the average self-published novella is because the publishers or institutions provided professional editing services to ensure quality. I – Carla Hurt – did not write a book of clear, flowing prose with consistently good Latinitas (just ask my editor…!); I wrote a manuscript which was then heavily edited and turned into a quality book. This didn’t destroy my authorial vision – it brought my authorial vision more sharply to life in a way I could never have achieved without the editor.

Most people don’t realise this, but no one is a good writer, even when writing in their native language, without a good editor. By ‘editor’ I mean a line editor: someone who reads the text and advises on changes to sentences and paragraphs to improve flow, readability, factual accuracy, and language consistency. This type of editor makes copious changes to the wording of sentences and may even advise for whole paragraphs to be rephrased, deleted, or inserted. Their work is at a totally different scale to that of the proofreader, whose job is only to catch spelling, formatting, and obvious grammar errors at the word-level.

It takes a significant amount of professional labour to edit a book properly, and it significantly changes the wording of that book, which is why editors should cost hundreds of dollars at least, scaling up and down with the size of the book project and the experience of the editor. Sending copies of your manuscript to a group of fellow Latin teachers of similar skill level who proofread it for free in their spare time without any training in the publishing industry is not the same as hiring a professional editor – not by a mile.

The problem with saying ‘why don’t you write a better book then’ is that it is not the individual writer’s skill which determines the final quality of the book, but the combined skill of the writer and their editorial team. Writing a book manuscript by yourself and self-publishing it using the same proofing process that most CI novellas currently use will result in similar outcomes as most CI novellas. Just because someone can publish 20 books the wrong way doesn’t mean they are an expert on publishing a book the right way. It just means that they have been a cowboy 20 times and are now telling other people to do the same thing, or else hold their tongue about novella quality. This is bad advice. We should be getting our publishing advice from publishing professionals, not from Latin teachers, and we should not be encouraging people to publish without them learning what that process entails.

When I first started observing the flurry of CI novella publishing in 2021, I thought that with enough books written and enough authors involved, eventually some higher quality ones would appear, until the books were at the same level as traditionally published media. This did not happen, because I had a fundamental misunderstanding of the book writing process. Writing quality is not the result of authorial brilliance or sheer luck. It is the result of tried and tested processes which traditional publishers developed over many years, and which the most successful self-publishers replicate by hiring professional editors.

We need to move from putting all the responsibility for book publishing on the shoulders of authors to helping people find what really works. But that is a derivative discussion. In order to encourage, promote, sponsor, or subsidise professional editing services to provide avenues for improving CI Latin materials, we have to first be able to honestly look at and discuss the results of current self-publishing practices. Are things as rosy as we make them out to be? Are we covering up the differences in quality between self-published and traditionally published books, which are the results of structural inequality? Are we perpetuating an inequality of access to professional editors in CI Latin? This is what we are doing to ourselves when we silence public criticism of CI Latin novellas.

Attempting to silence public error discussion is also damaging to the CI movement in other ways. The consequence of policing public negativity is to foster both false positivity and hidden negativity. To someone who first stumbles upon CI Latin novellas, like myself in 2021, it looks like everyone is only positive about everything that is in them, and this sets them up to be more disappointed by the editing quality of the real product than if they had a better idea of what they were getting into ahead of time.