A while ago, I tallied up the Latin words for kill. Today I’m doing something different: I’ll be studying the Greek words for love. Can I hear an “aww” from the audience? Or… was that a sigh of impatience?

Because to be honest, I’m tired of people talking about the Greek words for love. It’s a staple of church sermons, and I think in the course of time a lot of misconceptions have developed around the Greek words. Etymology (or often folk-etymology) is one of the oldest rhetorical devices for moving into a meditative discussion of the “real”, “true” or “original” concepts behind words. Talking about the concepts is good, but I’d like it if people made less fudgey mistakes about the language in the process. What I take issue with is the unwary and unthinking focus on the exact meanings of individual words outside of their context. And the endless talk of two Greek verbs for love, agapaō and phileō, is possibly the most meticulously bungled case of them all.

Because no matter what language you speak, love makes more sense in context than on a vocab list. Let’s explore.

Greek biblical texts

Because of time constraints, and because the biblical texts are mostly what people will want to apply the meanings of “love” to, I’ll be looking at the Septuagint (aka the LXX, a Greek translation of the Old Testament used in the time of the apostles) and the Greek New Testament.[1]

How many Greek words are there for love?

Anyone who googles “how many Greek words are there for love?” will get a range of numbers between about three and seven, but most commonly four. The list always includes the nouns agapē and philia (which form the verbs agapaō and phileō, respectively). Agapē is styled as the most god-like love and philia is considered the human love or in some way a lesser love.

The next most common nouns on the list (or verbs; sometimes people mix the two) are erōs and storgē. Erōs is usually used to say what agapē and philia cannot be – erōs is described as the sexual love, the lustful love. It’s an odd choice in the discussion of biblical love concepts, though, because as we will later see, biblical Greek uses other words instead of erōs when it talks about lust, sometimes even agapē and agapaō (if you interpret Amnon’s incestuous love for his beautiful half-sister as “lust”).[2] In fact, erōs does not appear at all in the New Testament and only appears twice in the LXX.[3] Storgē (sometimes misspelled storgy) is also an interesting choice, because it is never used in the NT or the LXX, except in two compound adjectives astorgos (“callous, un-loving”, which appears twice)[4] and philostorgos (“deeply loving”, which appears once).[5] To the list compilers, though, a word in Greek must be precious even if it is irrelevant, so they usually include it and say that storgē is the love of parents for their children, or more broadly a kind of familial love.

There is a likely reason why the list is so often four items long, and so often contains erōs and storgē. The “four loves” may not be found in the bible but they are featured in C. S. Lewis’ highly acclaimed book, “The Four Loves”.

“The Four Loves” was a philosophical and meditative study on the types of love Lewis felt he could describe and experience. The work is complex and subtle: Lewis talks about a lot more than just four loves in “The Four Loves” through his exploration of need-love and gift-love, and various other qualities that make various loves more or less suited to different relationships. The Greek terms philia, erōs and storgē appear in the book, but it seems that Lewis uses these terms for convenience’s sake as much as anything, and he uses Latin terms such as amicitia and “Venus” as well. Summaries of “The Four Loves” frequently trivialise most of what Lewis says about the types of love he investigated, flattening each of the loves into stereotypes that would have the man roll in his grave.

Whatever else appears on the “Greek words for love” lists, seems to be a kind of mix-and-match of a few other Greek nouns or verbs or adjectives used as love or affection or goodwill or desire or madness – epithumia, eleos, thelēma, eunoia, mania, hēssaomai, hetairos (that’s not a word for love), aphroditios (belonging-to-Aphrodite? Seriously?), and so on and so forth. The most significant of these “other” words is epithumia, because it is a fairly common word for “desire” in the New Testament. There isn’t any further point to defining the rest of the Greek words for love, since they don’t occur very often in the texts under investigation. Let’s ditch the dictionary-style approach and turn to looking at the situational usage of words for love.

Situations where the words for “love” may be used

The words for love can turn in several different contexts. Where each word gets used will give us a clue as to the range of meanings it can have. This isn’t an exhaustive list of what the words for “love” could mean, and some of these categories blur into each other. But for now it should give a good sense of how stretchy semantics can be. So let’s review some of the situations where a word for “love” could be inserted into the passage:

- The love between persons who have romantic attraction

- Lustful and harmful desire (in the form of vice lists)

- Love of concepts, actions or things – love of wisdom, love of folly, love of eternal things, love of material things

- Commands for Christians to love our neighbours and love God

- Love of God for his people

- The love that God the Father shows to the Son

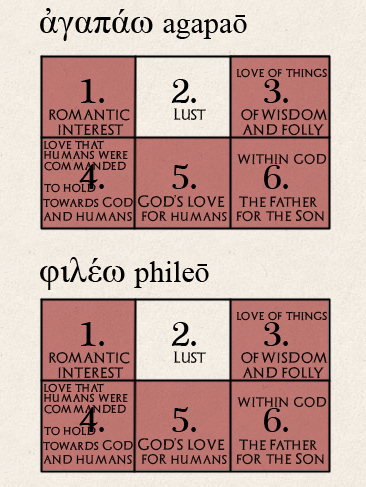

Now that we’ve outlined the categories, I’ll show you the results of what meanings each verb can cover, in table form.

Actual usages of “love” in biblical Greek

If a number is shaded in, that means that the verb was used that way at least once in biblical literature.

Agapaō and phileō are the most common verbs for love in the LXX and the NT. The semantic range of each of these verbs is very similar, and in most cases (including those situations involving God’s love) they can be used interchangeably. The fact that they can also be used in situations of romantic interest doesn’t necessarily mean that they must have this connotation outside of that context. Rather, context does a much better job at explaining what kind of “love” is meant.

The next most common verb for love is epithumeō, a verb which is usually translated as “to have desire for”.

Epithumeō can be used in both a positive and a negative sense. In the positive sense, it represents a desire for something which is good; in the negative sense it is a desire for something not good. It isn’t used in any of the times where the writer exhorts the audience to love one another or to love God, nor is it used of God loving anything.

The verbs storgeō and eraō are not used in the NT or in the LXX. However, erōs, the noun, does appear twice in the LXX with the negative connotation of “lust”.[6] These minor words will be excluded from the survey.

The pattern which emerges from this is essentially that agapaō and phileō, the most common verbs for love, are both used in a wide variety of circumstances, with both positive and negative connotations. Moreover, their meanings overlap each other, such that they have pretty much the same semantic range. In fact agapaō and phileō have a lot more in common with each other than they do with any of the other verbs for love.

In the following sections, I’ll show you where these meanings for “love” were found.

1. The love between persons who have romantic attraction

Words used: agapaō, phileō, epithumeō.

In each of the following cases, a word for love was used in situations which obviously have some sort of romantic interest, whether it was for good or for bad. Song of Songs mainly used agapaō with one instance of epithumeō to describe the dynamic between the lover and the beloved. The sad soap opera that played out between Jacob, Rachel and Leah used agapaō as the verb for love. Even the disastrous love affair of Samson and Delilah used agapaō as the verb to denote their affection. Tobit uses phileō to describe his feelings for his wife when he found out who he was going to marry.

| Quoted passage | Word for love used |

| (Song of Songs 2:3) I desired his shadow, and sat down, and his fruit was sweet in my throat. | epithumeō |

| (Song of Songs 2:4) He brought me to the banqueting house, // and his intention toward me was love. | agapē |

| (Gen 29:18-32) Jacob loved Rachel; so he said “I will serve you seven years for your younger daughter Rachel.” … So Jacob went in to Rachel also, and he loved Rachel more than Leah. … Leah conceived and bore a son, and she named him Reuben; for she said, “Because the Lord has looked on my affliction, surely now my husband will love me.” | agapaō |

| (Judges 16:4-15) After this, he [Samson] fell in love with a woman in the valley of Sorek, whose name was Delilah. … Then she said to him, “How can you say, ‘I love you,’ when your heart is not with me? You have mocked me three times now and have not told me what makes your strength so great.” | agapaō |

| (Tob 6:19) When Tobias heard the words of Raphael and learned that she was his kinswoman, related through his father’s lineage, he loved her very much, and his heart was drawn to her. | phileō |

But there is a much more tragic use of the word “love” in the tale of Amnon and Tamar. To me this is perhaps the saddest of all the various catastrophes and royal crimes committed in David’s house. The prince Amnon was seized with love for his half-sister Tamar, a love that was incestuous and violent. When eventually he tricked Tamar into his bedroom alone, he raped her, and it was said that his hate for her exceeded his incestuous lovey-lust. Throughout this passage Amnon’s “love” was called agapē. (Amnon got his comeuppance, as his half-brother Absalom killed him in revenge soon afterwards, but it’s still a tragic story for Tamar.)

| Quoted passage | Word for love used |

| (2 Sam 13:1-4) David’s son Absalom had a beautiful sister whose name was Tamar, and David’s son Amnon fell in love with her. … Amnon said to him, “I love Tamar, my brother Absalom’s sister.” | agapaō |

| (2 Sam 13:15) Then Amnon was seized with a very great loathing for her; indeed, his loathing was even greater than the lust he had felt for her. | agapē |

2. Lustful and harmful desire (in the form of vice lists)

Words used: epithumeō, and a wide range of others.

As said earlier, most people who think of the Greek word for sexual love will generally think of erōs. However, the word almost never appears in the bible, and classical uses of erōs don’t limit it to just meaning the lust of the body.[7] Instead, the biblical writers used other words like epithumia/epithumeō (desire). In longer lists, the writers used many more words to denote various kinds of vice that had a sexual tinge.

| Quoted passage | Word for love used |

| (Matt 5:28) But I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her in his heart. | epithumeō |

| (Col 3:5) Put to death, therefore, whatever in you is earthly: fornication, impurity, passion, evil desire, and greed (which is idolatry). | porneia (fornication) akatharsia (impurity) pathos (passion) epithumia kakē (bad desire) |

3. Love of concepts, actions or things

Words used: agapaō, phileō, epithumeō, thelō

This is the broad category for love of things which aren’t people. Loving something which is good, like wisdom, is a good thing, while loving something bad, like folly, is bad. Some things which you can love (like tasty food) are indifferent, neither good in themselves nor bad, but it depends on the situation. It seems that agapaō, phileō and epithumeō can all be used to denote love of non-person entities, whether they are good, neutral or bad. But epithumeō, more than the other two verbs, implies a kind of desirous craving.

I’ve divided this section into five subcategories: love of wisdom, folly, status, material things, and food.

3.a Love of wisdom

| Quoted passage | Word for love used |

| (Prov 12:1) Whoever loves discipline loves knowledge | agapaō |

| (Prov 8:17) (the personification of Wisdom is speaking in the first person) I love those who love me | agapaō (for Wisdom’s love)phileō (for “those who love Wisdom”) |

| (Wisdom 6:11) Therefore set your desire on my words; // long for them, and you will be instructed. | epithumeō |

3.b Love of folly

| Quoted passage | Word for love used |

| (Ps 52:4, or Ps 51:5 in the LXX) You love evil rather than good, // falsehood rather than speaking the truth. | agapaō |

| (Ps 4:3) How long will you love delusions and seek false gods? | agapaō |

| (Rev 22:15) …everyone who loves and practices falsehood. | phileō |

3.c Love of status

| Quoted passage | Word for love used |

| (Luke 11:43) “Woe to you Pharisees, because you love the most important seats in the synagogues and respectful greetings in the marketplaces.” | agapaō |

| (Luke 20:46) “Beware of the teachers of the law. They like to walk around in flowing robes and love to be greeted with respect in the marketplaces and have the most important seats in the synagogues and the places of honor at banquets.” | thelō (“wish, want”, translated here as “like”)phileō (translated as “love”) |

3.d Love of material things

| Quoted passage | Word for love used |

| (Ecclesiastes 5:10) Whoever loves money never has enough; // whoever loves wealth is never satisfied with their income. | agapaō |

| (Deuteronomy 14:26) Use the silver to buy whatever you desire: cattle, sheep, wine or other fermented drink, or anything you desire. | epithumeō (used in a neutral sense) |

3.e Love of food

| Quoted passage | Word for love used |

| (Gen 27:4-9) “Prepare me the kind of tasty food I like and bring it to me to eat…”… “Go out to the flock and bring me two choice young goats, so I can prepare some tasty food for your father, just the way he likes it.” | phileō (used in a neutral sense) |

| (Prov 23:3) Do not crave his delicacies, // for that food is deceptive. | epithumeō |

4. Commands for Christians to love our neighbours and love God

Words used: agapaō, phileō

The exhortations to love are some of the most powerful verses in scripture for Christians living today. In sermons, this is the point where the speaker is the most likely to claim that love is only called agapē, mainly because the speaker wants to make the point about the importance and selflessness of true, good love. This is well-intentioned, but unfortunately not entirely accurate, as Paul urged his fellow believers to love each other using the imperative of phileō. Paul also made a very pointed remark at the end of one of his other letters, (he was probably frustrated by all the Corinthian church problems he had to advise about in the rest of the letter) basically saying anyone who doesn’t love (phileō) the Lord should be an anathema.

| Quoted passage | Word for love used |

| (Mark 12:30-31, quoting Lev 19:18) ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength.’… ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ | agapaō |

| (Romans 12:10) Be devoted to one another in love. Honor one another above yourselves. | phileō |

| (1 Corinthians 16:21-2) (this is the end of a long letter in which he had to deal with a lot of heresy, so it’s understandable that he was quite frustrated) I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand. If anyone has no love for the Lord, let him be accursed. … The grace of the Lord Jesus be with you. | phileō |

5. God’s love for humanity

Words used: agapaō, phileō

The love God shows for humanity is most often, in sermons, said to be agapē (noun) or agapaō (verb). Usually this is connected to the above point – agapē is the selfless love that God has, while phileō is a kind of lesser love (strangely, people usually supply phileō the verb, alongside agapē, the noun – maybe they just sound better that way). But while agapaō is certainly a more common verb and is more commonly used to denote God loving human beings, there are instances where phileō is used in the same place to mean more or less the same thing. John is particularly interested in the love that God shows for humanity, and he switches agapaō around with phileō in two very similar verses. The quotes from Hebrews (or properly Proverbs) and Revelation are even more strikingly similar, and they freely switch agapaō and phileō around.

| Quoted passage | Word for love used |

| (John 3:16) For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life. | agapaō |

| (John 16:27) the Father himself loves you because you have loved me and have believed that I came from God. | phileō |

| (Heb 12:6, quoting from Prov. 3:11,12) the Lord disciplines the one he loves, // and he chastens everyone he accepts as his son. | agapaō |

| (Rev 3:19) Those whom I love I rebuke and discipline. | phileō |

6. The love that God the Father shows to the Son

Words used: agapaō, phileō, eudokeō

Surprisingly, in this section I actually had more trouble trying to find an example where God the Father loved the Son using agapaō rather than phileō. The best I could come across was an adjective formed from agapaō, which was agapētos, or “beloved”. Since this is the kind of love which one member of the Godhead has for another member of the Godhead, this has got to be pretty much the most Godly of Godly kinds of love. And John evidently found it acceptable to use phileō in this instance.

| Quoted passage | Word for love used |

| (Matthew 3:17 ) “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased.” | agapētos (beloved, from agapaō)eudokeō (to be well pleased [with someone]) |

| (John 5:20) For the Father loves the Son and shows him all that he himself is doing. | phileō |

Conclusions

The more you read Ancient Greek, English, Latin, or any language, the more you start to appreciate the semantic range of the most common words. Phileō, a verb for love, could be used to describe the love that God the Father had for God the Son. The same word, in another context, could simply mean “I like food.” The sentences “Samson loved Delilah” and “Amnon loved Tamar” could use agapaō, even though these were tragic and foolish loves, and Amnon’s love was perverted. That didn’t ruin agapaō, or make it unacceptable to use in other situations; agapaō was simply the word for loving. It was too common and too useful to get negative connotations from occasionally being used in negative circumstances. Thus it was just as acceptable to use agapaō for the intense couple-love in Song of Songs and the more fundamental love implied in the command, “Love thy neighbour”.

The net result is that you can’t understand a language from vocab lists alone. You have to have an ear and an eye out for contextual information.

[1] But the reader should not be under the impression that Greek only existed in the Bible. Koinē Greek, the dialect used in biblical texts, was a spoken and living language, and there were at least five centuries of written Greek literature before the writers of the New Testament put their pens to the papyrus.

[2] Amnon’s violent and incestuous lust for Tamar is called agapē in 2 Samuel 13:1-15. (LXX)

[3] Prv 7:18, Prv 30:16.

[4] 2 Timothy 3:3; Romans 1:31.

[5] Romans 12:10.

[6] Prv 7:18, Prv 30:16.

[7] In Plato’s Symposium the most common word for love was erōs, and it denoted a kind of enlightened pederasty. One of the earlier speakers said there could be a good erōs and a bad erōs; the bad version was typical of a “Popular Aphrodite” (Πανδήμου Ἀφροδίτης, Pandēmou Aphroditēs) who merely loved having sex with a good body (181a). Eventually, when Socrates spoke in the dialogue, he defined true erōs as the love of virtue in which no physical intimacy was ultimately necessary.

17 responses to “Greek words for love, in context”

Great post Carla! It certainly did mean they could express different kinds of love very clearly (unlike our English language where we really only fluctuate between ‘like’ and ‘love’) – But I had never heard of the C.S. Lewis connection before. I shall have to go and hunt out that book.

However, I must say I do prefer our English versions as there is a lot less to remember!

Thanks for your thoughts Matt! Though I’m not sure if I agree with you about English having too few words for love. :p The word has over 40 synonyms at thesaurus.com, like “affection” and “amity” and “adoration”, which all have various shades of meaning, like the way Greek words do… but it seems that most of the time, us native speakers of English are blissfully unaware of the complexity of our own language, even though we use it all the time. Thanks for the comment, though, it’s great to hear your perspective.

[…] Greek words for love, in context (fishedup.wordpress.com) […]

[…] Sweet Site: https://foundinantiquity.com/2013/08/17/greek-words-for-love-in-context/ […]

There are many English words, but love is not at the core of all of them. Lust is NOT love. Sex can or can NOT be love depending. There’s a lot of sex today without love. There is friendship, but that doesn’t have to involve love. There is family love which should never be confused with lust nor sex. The English language is twisted, distorted, and misinterpreted depending on an individual’s reason for using a specific word, such as deception.

[…] Greek words for love, in context – a post in which I found that, contrary to popular opinion, there are more than four words for love in Ancient Greek; that the differences between ἀγάπη [agapē] and φιλία [philia] are overstated; that ἀγάπη [agapē] is not, intrinsically, a more virtuous love as it is also used to describe sinful desire; that the word ἔρως [erōs] is barely found in the bible at all, and in Plato’s Symposium it was used to describe something deeper and more civilised than carnal attraction; and more. […]

[…] other things, like romantic love, unhealthy obsession or lust, or admiration for non-human objects (source). The root itself has a neutral connotation, although the context in which it has been, is, and can […]

[…] O arquivo original em inglês pode ser acessado aqui. […]

[…] love. I am unsure of the scope of this understanding of the greek words and can find some sources that suggest a variety of uses among them. Philia and Agape especially. The use of the word eros […]

Carla did not mention David and Jonathan and their kind of love: ala II Samual 1:26.

Interesting but I have to say that modern Greeks (I live on a Greek island) find it quite hilarious that we can ‘love’ the following: God, partner, child, pet, sex, home, food, shop, etc, etc.

[…] https://foundinantiquity.com/2013/08/17/greek-words-for-love-in-context/ […]

Very good study. I totally agree about context. We do our best to understand all things but must always realize we can only know ‘in part’ while in a fallen world.

As I’ve studied Agape (n), and agapao (v), I believe I’m closer to certain conclusions. As John tells us, God ‘is’ agape. I see this as one descriptive word of ‘what’ God is, not to be confused with ‘who’ He is, Supreme Creator. What comes from God, I see as agapao. With agape as the noun, and agapao as the verb, it personally helps me understand better. Studying agape, I keep in mind, this is what God literally ‘is’. (Again, only one descriptive word). 1 Cor 13- the love chapter. Agape is patient, agape is kind, etc. I also say God is patient, God is kind, etc., I believe is the same.

To conclude, God is agape, and how He demonstrates Himself is in agapao. For me personally, it helps me understand His pure and total goodness. The enemy has painted such a fearful image in the minds of so many. Understanding what He ‘embodies’ helps me communicate to so many who are suffering.

Another caveat, Jesus would not have spoken the word agape. He would have spoke whatever Aramaic word they used for love. I do believe the Greek translators were divinely enabled by the Holy Spirit for us to dig for a better understanding.

[…] range of meanings and is dependant upon the context. For example, in the Septuagint, the word agape is used for God’s love for us (Deut. 4:37), our love for our neighbor (Lev. 19:18), but also […]

Hello and thanks for sharing this! I have a question; how did Romans (and other Latin language users) deal with this? Are there equivalent Latin words, or did they loan the Greek words in latinized spelling? Thanks!!

[…] Hurt, C. (2013, August 16). Greek words for love, in context. Found in Antiquity. https://foundinantiquity.com/2013/08/17/greek-words-for-love-in-context/ […]

[…] Hurt, C. (2013, August 16). Greek words for love, in context. Found in Antiquity. https://foundinantiquity.com/2013/08/17/greek-words-for-love-in-context/ […]