Welcome back to the task of reading a real 11th century Latin manuscript of Vergil’s Aeneid. In Part 1, we launched straight into the task of deciphering this delightful Carolingian Minuscule manuscript, learning some of the most frequent scribal abbreviations. But there are still many more devices to go. Firstly, though, I realise I hadn’t properly explained what was in our manuscript before, so I drew up a neat chart for what sections of the Aeneid it covers, along with links to plain text versions of everything you can find in the manuscript. And secondly I’ve provided a short chart which summarizes all the devices we learned in Part 1, in case you wanted to quickly check them up. In the third segment, we resume learning scribal abbreviations until we’ve exhausted all of the ones which occur in this manuscript.

Outline of Part 2:

- I. Manuscript contents

II. Brief recap of devices covered in Part 1

III. More scribal devices and abbreviations

I. Manuscript contents

Our manuscript, Harley MS 2772 (it needs a catchier nickname), covers parts of books 7, 8, 10, 11 and 12 of the Aeneid. It has three lacunae, and the final pages appear to have been bound together in the wrong order – folio 15 should have been inserted before folio 14. But at least the first part of the manuscript continues unbroken, a section which covers the latter half of book 7 and the first half of book 8.

| Page range | Contents | Transcript | |

|---|---|---|---|

| f.1r-f.6v | Aeneid 7.394 to end of book. | Text: [link] Translation: [link] |

|

| f.6v | argumenta Aeneidis sub nomine Ovidii (8) | Text: [link] | |

| f.6v-f.12v | Aeneid 8.1-652 | Text: [link] Translation: [link] |

|

| LACUNA | |||

| f.13r-f.13v | Aeneid 10.450-522 | Text: [link] Translation: [link] |

|

| LACUNA | |||

| f.14r | Aeneid 11.900 to end. | Text: [link] Translation: [link] |

|

| f.14r | argumenta Aeneidis sub nomine Ovidii (12) | Text: [link] | |

| f.14r-f.14v | Aeneid 12.1-43 with copious commentary | Text: [link] Translation: [link] Commentary: [link] |

|

| LACUNA | |||

| f.15r-f.15v | Aeneid 11.684-755 | Text: [link] Translation: [link] |

|

The argumentum before the start of each book is a summary of the main action of the book, written in the epic meter (dactylic hexameter). These argumenta are quite interesting in their own right, but they would have to be the subject of a separate blog post for me to do them justice. You might also enjoy reading the copious marginal notes at the start of book 12 on folio 14. I’ve added a link to the transcription of the medieval commentary in the table above in case you wanted to check if you were reading it correctly.

II. Brief recap

- The alphabet

- The long s

- Mandatory ligatures

- The m- or n-tilde

- The ae diphthong

- -que and -ibus

- The ampersand (&)

- The -ns and -nt ligatures

- The -i- ligature

The chart below summarizes the abbreviations we covered in Part 1, minus the first three sections (which were just about the normal shapes of the letters).

Now that we’re up to scratch, let us continue with the lesson!

III. More scribal devices and abbreviations

10: con-, com-

The prefix “con-” (or “com-” in words like “complere”) can be abbreviated to just the letter c with a tilde over the top. The con- abbreviation could be seen as a variation on the m- or n- tilde, since it uses the same small horizontal squiggle above the letter and the contraction includes the letter m or n.

It rises, then surges up from the deepest depth to the sky. (7.530)

11: per-

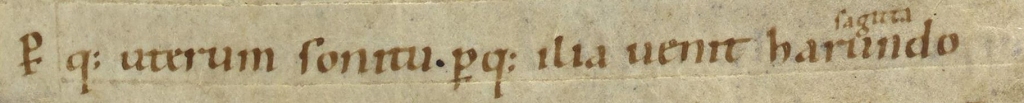

This is the first of three easily-confused abbreviations which start with a p: per, pro and prae. The letter sequence “per” can be represented by the letter p with a horizontal line cutting through the downstroke of the p from left to right. This sequence doesn’t have to occur only at the start of a word; words like “super” can also contain the per abbreviation.

The scribe who copied this line added a helpful note. The word “harundo” can mean reed or cane, but in this context it means arrow. It’s a rare word, however, so the scribe added the common Latin word for arrow, “sagitta,” above the more difficult word as a gloss.

The arrow went through the belly and the flank with a thud. (7.499)

12: pro-

The letter sequence “pro” can be represented as a p with an diagonal stroke which starts at the bottom-left corner of the round part of the p and hangs down to the left of the letter. To me it looks kind of like the loose end of a ribbon.

Sweat, having burst out, drenched his whole body. (7.460)

13: prae-, proe-, pre-

Rounding off our three p-abbreviations, the letter sequences “prae,” “proe,” and “pre” can be represented by a p with a horizontal squiggle on top. All of these sequences would have sounded the about the same in medieval pronunciation, the ae and oe diphthongs being often spelled simply as an e. So it’s natural that “prae,” “proe,” and “pre” would share the same abbreviation sign.

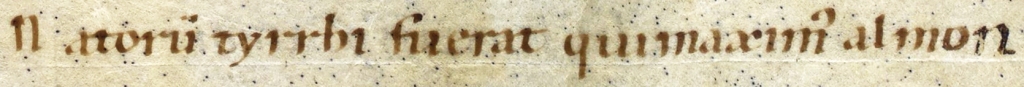

This line has a huge initial N because it represents the start of a section or chapter in this manuscript.

Nor was the founder of the Praenestine city absent (7.678)

14: -us (curly sign)

A small curly squiggle at the upper right-hand corner of a word can represent the ending “-us”. In theory, this sign can represent any vowel followed by an s, or even just an s by itself at the end of a word, but in this manuscript it seems to only represent -us.

…Almo, who was the eldest-born of Tyrrhus’ sons (7.532)

15: -us (-vs ligature)

There is a fair amount of overlap and redundancy in the system of medieval scribal abbreviations. The sequence “-us” can also be shortened into a ligature which looks more like a v superimposed upon an elongated s.

Try to avoid confusing this -vs ligature with the -i- ligature. The -i- ligature is indicated by an extended, slightly wavy vertical line at the bottom right corner of a letter, whereas the -vs ligature is a diagonal stroke just next to an s. There’s both an -i- ligature and a -vs ligature in the sample lines below.

![Exsultantque aestu latices, furit intus aquali [sic.] Fumidus atque alte spumis exuberat amnis And the liquid leaps up with fervour; the steaming torrent of water rages within and overflows high with froth (7.464-5)](https://foundinantiquity.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/us-vsligature-example.jpg?w=1024&h=166)

Fumidus atque alte spumis exuberat amnis

And the liquid leaps up with fervour; the steaming torrent of water

rages within and overflows high with froth (7.464-5)

16: -tur, -ntur, -mur

-tur, -ntur and -mur are common endings used in Latin passive verbs. The -ur part of the ending can be abbreviated to just a horizontal squiggle with a bump on top. If you look closely, and if the scribe hasn’t conflated the mark with all the other squiggly horizontal lines, this squiggle looks kind of like a flattened number 2. That’s the shape of an R without its vertical stroke.

‘Alas!’ he said. ‘We are being wrecked by the fates and borne away by a storm!’ (7.594)

17: -orum, -arum, -rum

The “-rum” part of the genitive plurals (-arum in the 1st declension, -orum, in the 2nd, and -rum in the 3rd and 5th) can be abbreviated to a mark which resembles a number 2 (or a capital R without its vertical stroke) that has a line striking through the tail. The main part of the symbol represents an r (which is the first letter of the abbreviated text), and the strikethrough line is one of the ways to show that something has been shortened.

The misspelled word in this sample, “laetum,” should be read as “letum,” (death). It is fairly common to find medieval manuscripts accidentally swapping ae’s for e’s and vice versa.

![respice ad haec: adsum dirarum ab sede sororum, bella manu laetumque [sic.] gero. Look at this! I am here, from the seat of the dread sisters; In my hand I hold wars and death. (7.454-5)](https://foundinantiquity.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/orum-example2lines.jpg?w=1024&h=165)

bella manu laetumque [sic.] gero.

Look at this! I am here, from the seat of the dread sisters;

In my hand I hold wars and death. (7.454-5)

As an aside: These sample lines featured something very strange – a question mark. The same mark is used later in the manuscript (in folio 8v) to indicate a series of questions in Aeneid 8.113-4. But in this passage, there is no question being asked. So then why is it here? Perhaps the question mark had more than one job, just as the centre dot in this manuscript can stand for either a comma or a full stop (period, for my American readers). Some scholars have suggested that ? was once a marker for a raised pitch in intonation, and for that reason it came to represent a question. Whether that theory is true or not, it doesn’t seem to be appropriate in this context. “I come from the seat of the dread sisters” sounds terribly underwhelming with a rising tone. My guess – and it is only a guess – is that this mark could also function something like an exclamation point.

If you were mystified by the strangely rotated angle of the ? here, you might want to check out the two more weirdly skewed examples below. Both of these date from much later manuscripts, and both of them actually represent questions. Clearly there was a range of angles that the question mark could be tilted at, for a long time after the period of our manuscript.

18: little letter ‘a’

This tiny letter is exactly what it says on the tin. It’s a little ‘a’, and it can be part of an abbreviation which includes the letter a.

![Indicit primis iuvenum et iubet arma parari he appointed [sc. a journey] for the first of his young men, and ordered them to prepare arms (7.468)](https://foundinantiquity.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/a-tinyletter-example.jpg?w=1024&h=72)

He appointed [sc. a journey] for the first of his young men, and ordered arms to be prepared (7.468)

19: -er

The following two devices look pretty much the same as the m- or n- tilde. However, if you know your Latin vocabulary, you can guess what kind of abbreviation is being indicated here. Below are a group of words which have had the letters “er” removed, and then indicated with a tilde.

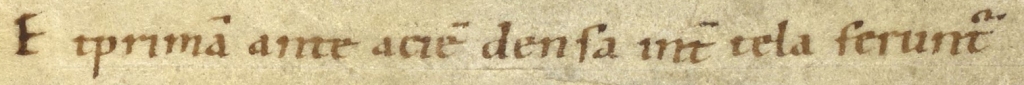

The example below contains two m-tildes, an -er abbreviation, and an -ur abbreviation. Since the most common use of the tilde is to indicate a missing m or n, if you see it written above a vowel, assume that it is an m or an n (unless it doesn’t make sense). If the horizontal squiggle is written above a consonant, use your common sense and your knowledge of Latin to make a best guess.

And they are brought before the battle-line, in the thick of weaponry (7.673)

20: -en

The abbreviation for -en can be considered a minor variation on the m- or n-tilde. Instead of just indicating a missing n, this tilde signifies that the letter sequence -en has been dropped. Once again, you will need to be somewhat familiar with Latin vocab. In the example below, I would remember that “nomm,” “nomn,” and “nomer” are not real Latin words, but “nomen” is, so the word must be “nomen.”

The bird having spoken; and now the name Ardea remains great (7.412)

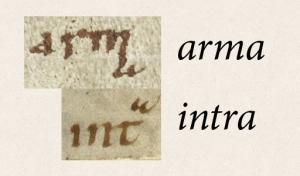

21. Common-word and sacred-word contractions

This is probably the most challenging and unpredictable category of scribal abbreviations. Before I continue, I want to reassure you that the vast majority of words in literary manuscripts are either spelled out in full or are contracted in ways that you can easily spot once you know what to look for. However, some common words (and some words that are common in sacred texts) are contracted in ways that are unique to each word, and these words can be written slightly different between different manuscripts.

Letters may be chopped off the end of the word, or else they can be removed from the middle. Sometimes the contracted word shows its case endings with the final letter. The contraction will usually be marked with an overline or a strikethrough line, just to show that the word has been contracted, without giving any clues as to what the missing letters were.

Below is a list of all the common-word contractions which occurred in the first section of our manuscript, until the end of Book 7 of the Aeneid. This is by no means an exhaustive list of all common contractions, as even my dictionary of Latin abbreviations (ed. Ulrico Hoepli) doesn’t even cover absolutely all the abbreviations that appear in manuscripts. But at least this gives you an idea of what these contractions look like, and what some of the more common ones are.

It is also important to be familiar with some sacred contractions. Even though the Aeneid is not a sacred text, through convenience or force of habit the scribe has abbreviated a few of the words which are also commonly abbreviated in sacred texts. Below are all the sacred-word contractions which occurred in our manuscript before the end of Aeneid Book 7. Note that a letter sequence like “sanctus” can be abbreviated even when it occurs within another word.

And below are some excerpts from the Book 8 of the Aeneid. Unsurprisingly, it helps to see abbreviations in context. If you can figure out the meaning of the rest of the sentence, you have a high chance of successfully guessing what the contracted word is, even if you haven’t seen it contracted like that before.

![Nimphae, Laurentes nimphae, genus amnibus unde est, Tuque, o Tibris tuo genitor cum flumine sancto, accipite Aenean et tandem arcete periclis. Nypmhs, Laurentine nymphs, [whose] birth is from the rivers, And you, o father Tiber with your sacred river, Receive Aeneas and save him at last from perils. (8.71-4)](https://foundinantiquity.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/common-and-sacred-abbreviations_example1.jpg?w=1024&h=227)

Tuque, o Tibris tuo genitor cum flumine sancto,

Accipite Aenean et tandem arcete periclis.

Nypmhs, Laurentine nymphs, [whose] birth is from the rivers,

And you, o father Tiber with your sacred river,

Receive Aeneas and save him at last from perils. (8.71-4)

Adloquere ac nostris succede penatibus hospes.’

‘O come, whoever you are,’ he said, ‘and in the presence of my father

Speak and draw near, guest, for our household gods.'(8.122-3)

Final thoughts

You made it! I hope you’ve enjoyed reading the Aeneid from a real 11th century Carolingian manuscript. If you would like to tackle large sections without interruption, you can click here for the beginning of the manuscript on the British Library’s manuscript viewer. Otherwise, you can consult the chart at the top of this page to choose a different part of the Aeneid. Finally, if you would like to delve deeper into reading manuscripts, or if you wanted a more systematic overview of scribal abbreviations, check out The elements of abbreviation in medieval Latin paleography by Adriano Cappelli, first published 1899, translated by David Heimann and Richard Kay in 1982. That introduction is fully available for free online.

One response to “How to read an ancient manuscript: 11th century Vergil’s Aeneid (Part 2)”

Superb blog post! I studied classics in college but never an actual manuscript. I feel confident about plunging into one with your 2-part orientation. Really wonderfully enlightening!